Overview of Major SAR Watersheds

Many of the basins in southern India and all in Sri Lanka and the Maldives are internal to the country although some of them may be quite large (e.g. Narmada, Krishna, Cauvery, Godavari, Mahanadi) and transboundary across sub-national boundaries. But most of the others are international transboundary watersheds.

The major transboundary river basins in South Asia are the Indus, the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna, and some of the Afghanistan-related Basins (Amu Darya, Helmand, etc.) as displayed in the map below.

Brahmaputra River Basin

The Brahmaputra River Basin drainage area is 580,000 km2; over half the drainage area (50.5 percent) is in Tibet, China; 33.6 percent in India; 8.1 percent in Bangladesh; and 7.8 percent in Bhutan. The headwaters of the Brahmaputra are in the Himalayas and flow into Assam, India before they reach Bangladesh. Prior the river reaching the Bay of Bengal, the river changes name to Jamuna after the confluence with the Teesta River, and the Padma between meeting a distributary of the Ganges River and the Bay of Bengal.

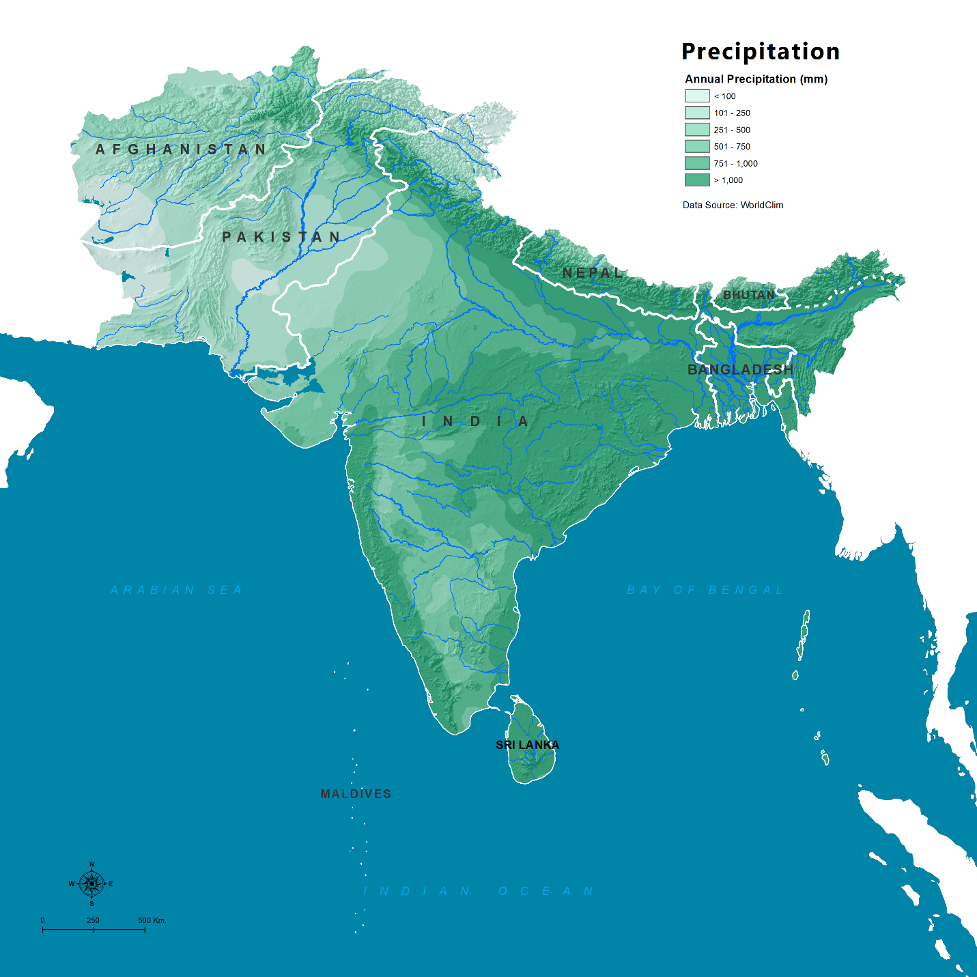

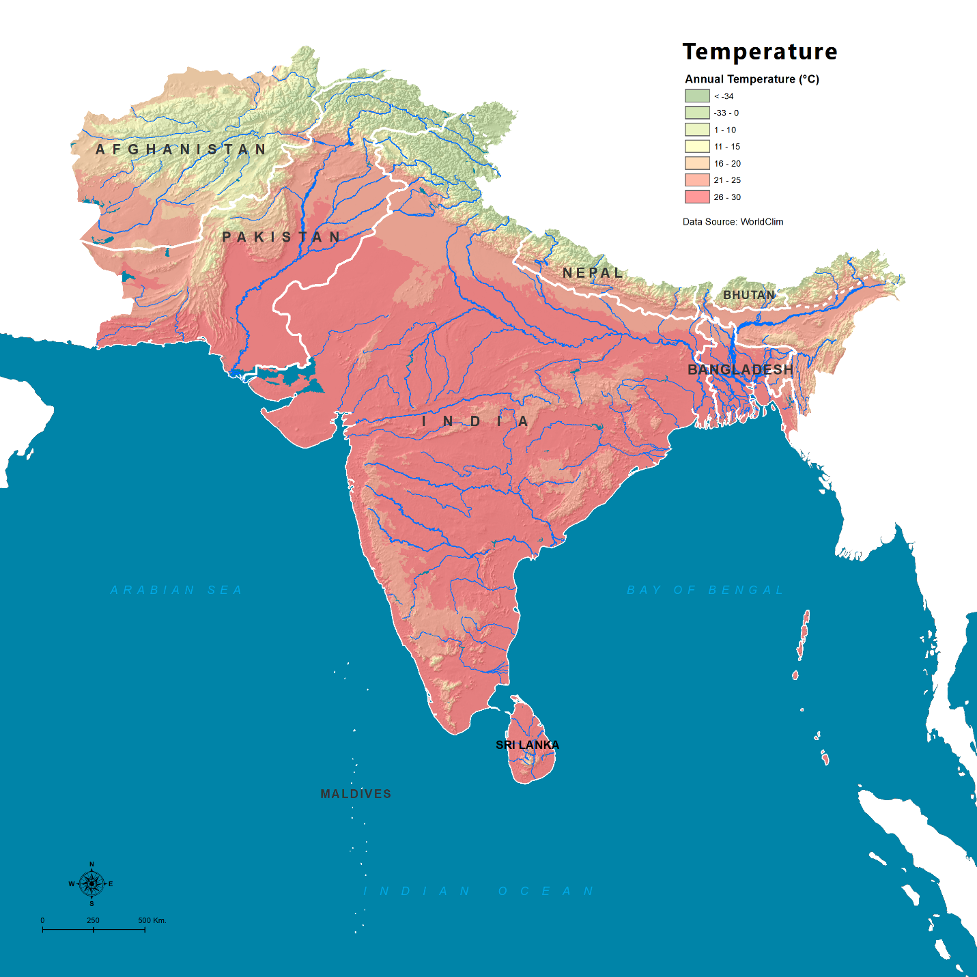

Average annual precipitation is 1100 mm, reaching a high of 2216 mm in the lower basin which is approximately three times higher than the upper part of the basin . Eight percent of the annual rainfall occurs during the summer annual monsoon that starts from late May or early June to the end of September. Average annual maximum temperature in the summer and winter is approximately 19.6 degrees and 9.2 degrees Celsius , respectively. The minimum average annual temperature in the winter ranges is -0.3 °C to 18.3 °C in the summer . Total annual flow in the river is 600 billion cubic meters from over 35 major tributaries. At Padma, there is significant annual variation in discharge where the recorded highs and lows are 72,794 and 1,757 cubic meter per second, respectively. The population within the basin is approximately 625 million people, of which 80 percent are farmers that use the water primarily for crops and livestock.

Ganges River Basin

With a population of 600 million, the Ganges River Basin has a drainage area of 1.086 million km2. The drainage area is distributed in India (79.2%), Nepal (12.85%), Bangladesh (4.28%), and Tibet (3.27%). Ganga, a sacred river, has its headwater in the Himalayan mountains. The Bhagirathi River is the source of the Ganges. The Ganges River flows in a south and southeasterly direction and enters Bangladesh at Farakka Barrage. Approximately 40 km downstream of Farakka Barrage, the river splits into two, with the Bhagirathi River entering the Bay of Bengal near Kolkata by flowing south. The other river, the Padma, flows easterly and enters Bangladesh to meet the Brahmaputra River at Goalundo and is now called the Padma. The Padma merges with the Meghna River about 105 km downstream at Chandpur. The flow discharges into the Bay of Bengal through a nearly 400 km wide delta.

Average annual rainfall in the basin is 1,000 mm, which varies from 350 mm on the western end of the basin to 2,000 mm of rain near the delta. Eighty-four percent of the average annual rainfall occurs primarily during the monsoon season in three months. The average maximum temperature across the basin in the summer and winter is 30.3 °C and 21.1° Celsius, respectively . The average minimum temperature across the basin ranges from 21.5 °C in the summer to 6.4 °C in the winter. The average annual flow is 1,200 billion cubic meters, with 250 billion cubic meters utilized in India. Ground and surface water is used to irrigate 19.5 million hectares.

Meghna River Basin

With a population of 29.37 million, the Upper Meghna River Basin has a drainage area of 82,000 km2. The drainage area is distributed in India (57%) and Bangladesh (43%). The Meghna river's headwater is in the hilly mountains in Eastern India and flows southwesterly to join the Ganges and Brahmaputra prior to being discharged into the Bay of Bengal.

The average annual rainfall is the highest in the Meghna Basin at 4 ,900 mm, which ranges from 2,150 in Bangladesh to 6,000 mm in the foothills of Meghalaya, India . Precipitation occurs primarily during the monsoon season from June to October. The average annual temperature is 23°C . The flow from India to Bangladesh, the flow is at 48 BCM, while at Bhairab Bazar, the yearly average flow is 145 BCM .

Indus River Basin

With a population of 300 million, the Indus River Basin has a drainage area of 1.12 million km2. The drainage area is distributed in Pakistan (47%), India (39%), China (8%), and Afghanistan (6%). The perennial river's headwater is in the Himalayan mountains and flows southward to Pakistan's Sindh province before eventually discharging into the Arabian Sea. The Indus River has two main tributaries: the Kabul and the Paniand that comprises five rivers (Jhelum, Chenab Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej).

Climatic variables such as precipitation and temperature are controlled by altitude. The average annual rainfall is 365 mm , where the v alley receives 100-200 mm, 600 mm rainfall occurs at an altitude of 4,400 meters, and 1,500-2000 mm of rain occurs at an altitude of 5,500 meters . Snowfall that occurs above an elevation of 2,500 meters accounts for most of the rainfall. Precipitation occurs during the winter and spring and emerges from the west. The average maximum temperature in the summer and winter is 30.0 °C and 13° Celsius, respectively, while the average minimum temperature ranges from 18 °C in the summer to -0.3 °C in the winter . Streamflow is comprised of glacier melt, snowmelt, rainfall, and runoff. The Upper Indus Basin has a glacial area of 22,000 km2, and the snow area is greater by one order of magnitude. The average annual flow is 243 km3 with glaciers providing natural water storage.

Amu Dary River Basin

With a population of 50 million people, the Amu Darya River Basin has a drainage area upto to 534,739 km2; the exact figure is not known since the basin area can only be calculated in the upstream portion of the basin. As such, countries' disaggregated areas make up basin Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan cannot be calculated. The Amu Darya headwaters are in the mountainous regions of Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and the Pamir glaciers. The Amu Darya River's start is the confluence between the Pyanj River and flows towards the northwest. After leaving the highlands, the river flow passes the Turan Plain that forms the Karakum and Kyzylkum Deserts boundary before it is conveyed into the southern portion of the Aral Sea. The lower reach is the geographic boundary between Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

Average annual precipitation ranges from over

1000 mm in the alpine areas to under 100 mm in the deserts Eighty percent of the occurs during the winter and early spring . The average annual temperature ranges from -30 °C to 30 °C. The mean annual flow is 78 KM3, with 80 percent of the flow generated in Tajikistan . Flow to the Aral Sea is significantly reduced before it enters into the Aral Sea from evaporation, irrigation withdrawals, and infiltration. Ground and surface water is used to irrigate 5 million hectares .These watersheds can be explored in their overall sustainability content, from social, environmental, and economic viewpoints. Although many of these are intertwined, there are also a number of explicitly cross-cutting thematic areas.

Social

Population

South Asia is a densely populated region, marked by high population growth

Population in South Asian countries increased over a period of six decades from 1960 to 2019.

The following provides an interactive portal showing South Asia’s population density (basin-wide).

Poverty

Poverty levels in South Asia are high and the region accounts for a third of the global poor.

The chart below shows the poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population) in South Asian countries from 1977 to 2017. Data is based on primary household survey data obtained from government statistical agencies and World Bank country departments.

Although the population growth in the region is decreasing, per-capita water availability continues to fall across all the countries of South Asia.

Gender

Gender equality is a major challenge in access to water and sanitation in south Asia.

Traditional women’s role in most societies include the management of household water supply. Water is necessary for multiple domestic chores and productive activities of which women are responsible of. Water is essential not only for drinking, but also for food preparation, care of domestic animals, care of the sick, cleaning and waste disposal.

According to the UN, women and girls assume water collection tasks in 8 out of 10 households. Sometimes water sources are far from their homes, which means girls are more likely to drop school due to the lack of accessible water. Women are also vulnerable to die from unclean births. Infections not only affects mothers but also newborn babies. Improving the access to better drinking water services will help increase girls’ education access and prevent many childbirth deaths and other low sanitation related deaths.

Getting to Equal in Water: How to Improve Gender Equality in Water Institutions

Human Development

The Human Development Index is improving in South Asia.

Economic growth is measured by GDP but doesn’t consider human capacity. The Human Development Index (HDI) considers three dimensions: life expectancy, expected educational schooling, and a decent living standard using gross national income per capita. In South Asia, Sri Lanka and the Maldives lead the region with high human development, while Afghanistan is the only country that falls under low human development.

Economic

Macroeconomic

Afghanistan, the Maldives and Sri Lanka, which report their real GDP growth rate in a calendar year, grew at 3.9, 7.0 and 2.3 respectively in 2019 and contracted to –5.5, -21.5 and –5.5 in the following year of the COVID-19 pandemic. The remainder of South Asian countries report their real GDP growth in a fiscal year format with Bangladesh's growth at 8.2, Bhutan at 4.3, India at 6.1, Nepal at 7.0 and Pakistan at 1.9 in the 2018/19 with 2019/20e figures dropping down to 2.0, 0.7, 4.2, 0.2 and –1.5 respectively. The South Asian region is projected to grow by 3.3 percent in 2021 and 3.8 percent in 2022. Weak growth prospects reflect a protracted recovery in incomes as well as employment, especially in the services sector. Output in 2022 is projected to remain about 16 percent below pre-pandemic levels, the biggest loss among EMDE (Emerging Market Developing Economy) regions ( Global Economic Prospects report 2021 ).

The region can sustain high growth only if investments and exports both grow stronger. Since April 2020, the World Bank has delivered $7.9 billion to support COVID-19 recovery in South Asia. For example, in India, a $210 million project in the state of Maharashtra will help over 1 million farming households access emerging domestic and export markets, increase private sector investment in agricultural value chains, increase productivity, respond to price fluctuations, and build crop resilience.

Agriculture

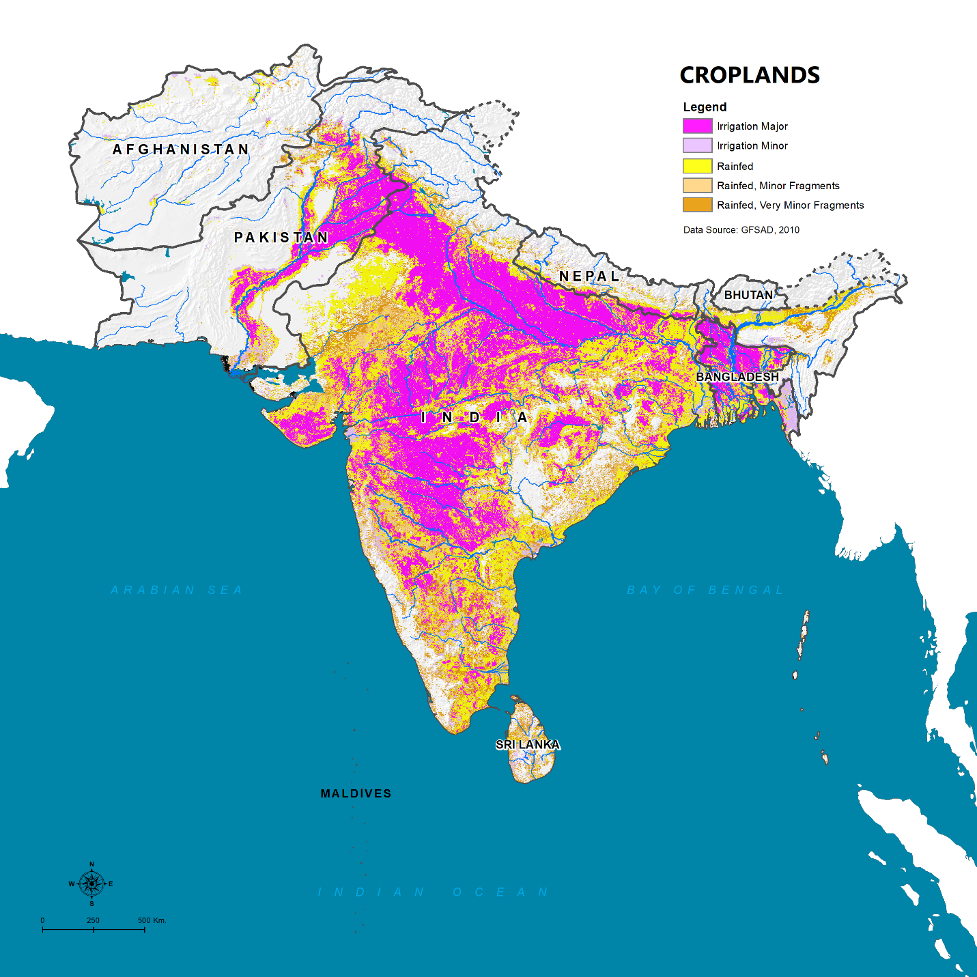

Agriculture consumes most of the water in South Asian watersheds.

South Asia feeds about 20% of the population, with only 3% of the land. Over 90 percent of the freshwater is currently used for agriculture, as shown in the nearby figure.

Energy

Hydropower: Hydropower development in the region is far below its potential (some estimates suggest that about 80% of its potential is untapped). The current estimate of hydropower and power generation are shown in the figures below. Given the significant social, environmental, technical, and investment issues for develop of large storages, much of the ongoing development has focused on run-of-river systems. Many of these face challenges from siltation, very seasonal and variable flows, hydraulic safety with flash floods and landslides, and high electricity transmission costs.

Transport

Given the regional population of over 2 billion people spread across both densely developed urban areas and remote rural villages, the South Asia region’s transportation infrastructure needs are enormous. Transportation is intricately tied to the social and economic well-being of populations as it provides connectivity and access to important goods and services, such as markets and health care. The transportation sector, and especially the construction and maintenance of rural roads in hilly areas, also has an important development interface with both watershed-scale erosion management and disaster risk management. Without proper mitigation measures, roads and road construction can increase erosion and sedimentation into waterways, with downstream impacts to other sectors. Road construction can also trigger landslides, which lead to direct impacts to lives and livelihoods, and connectivity losses in the broader watershed.

Sustainable transportation includes road safety measures; clear rules and regulations; and clean transportation technology. The World Bank has an active regional transportation program in the area with multiple projects, including work on bolstering inland waterways for cargo.

Urbanization & Industrialization

Other water demands are expected to increase rapidly as the region urbanizes and industrializes.

Municipal: As the region urbanizes, more towns are becoming cities, and cities megacities, with a large water supply footprint to meet their domestic, commercial, and fire-fighting needs. Domestic water shortages are significant today in many areas, both due to the availability of water due to growing use in other sectors and the problems of water supply utilities and infrastructure. These result in long wait times at standpipes and high incidence of water-related diseases. It has been estimated that 22 out of 34 major Indian cities are facing daily water shortages. Citizens in Kathmandu, Nepal, have water shortages and have extremely long wait times . In Pakistan, unclean water is related to 40 percent of death and 30 percent of disease . The Asian Development Bank report in 2016 analyzing water security determined that South Asia household water security is considered hazardous based on water supply, sanitation, and the impact of diarrhea. Country values rankings are shown in the figure.

Industrial: Industrial water productivity is measured to be high for the countries in South Asia as shown in the figure, with India and Bangladesh, the major water consumers, using two percent of the total water withdrawals. In India, water demand is primarily used for cooling of thermal power plants and is the fastest-growing sector. Bangladesh's primary water user is in the garment industry. In Pakistan, the largest industry is textile production, with a blue water footprint of seed cotton is 5258 m3/ton versus the global average of 3,253 m3/ton .

Environmental

Watersheds experience a range of environmental challenges. These can include issues of climate, land, water, ecosystems, pollution and other aspects.

Countries in South Asia are incredibly diverse regarding climate, diversity, and landscape, while most countries share common watershed challenges. Major challenges facing the region are soil degradation, soil erosion, deforestation, water pollution, land degradation, and desertification that is caused by total population growth and the migration from rural to urban areas. As population increases, there is a greater requirement to convert forested areas to agricultural lands or put marginal lands into agricultural production. Other needs for forested products are firewood and timber for building construction. When forests are degraded or impaired, it causes a loss of biodiversity and habitat in the watershed. The rural-urban migration converts open space to impervious space that will increase flooding, cause soils and water erosion downstream and increases water pollution.

The region’s rapid socio-economic growth has placed considerable stress on its natural resources.

With 25 percent of the world’s population and 4.5 percent of the available freshwater resources, water availability and water quality have a detrimental impact on the watershed. As a result of the green revolution to increase food security, ~90 percent of the freshwater resources is applied to agriculture production, including 80 percent of the groundwater resources. This overexploitation of groundwater resources reduces drinking water availability and the protection of environmental resources and affects water quality. In Bangladesh, the exploitation of shallow groundwater resources has increased arsenic pollution. Arsenic is not just limited to Bangladesh since the entire GBM has high levels of arsenic concentration. Arsenic concentrations have been measured in food material of up to 3,947 µg/kg, irrigation water at ~1,000 µg/L, and groundwater concentration have reached up to 4,730 µg/L, which in all cases is above WHO standards. Other sources of water pollution include the disposal of human waste without treatment and from the manufacturing process. India CPCB (Central Pollution Control Board) has estimated that about 63 percent of urban sewage flowing into the river is untreated.

Forests

Deforestation for crop production and human settlement has had a significant impact on biodiversity. South Asia has deforested over a million km2 and added over 1.5 million km2 of croplands since the 1700s. Deforestation is still ongoing, with one recent estimate in India for industrial projects is 14,000 km2 within the past thirty years. The overall impact of deforestation will affect biodiversity, hydrology, and erosion since the tree roots no longer anchor the soil.

Forest cover is declining, with many areas of forest loss in the last couple of decades.

From 2001-2019, all countries in SAR have seen their forest cover decline, while India and Bangladesh are displaying significant decreases. Significant drivers of deforestation for each country are shown in the chart below. The location of deforested areas for South Asia is shown on the map.

The following chart shows the forest area (as % of total land area) for South Asian countries over a period of fifty-six years from 1960 to 2016. Bhutan stands out as a country with commitment to preserve and protect its high forest coverage. Except for Bhutan and India, other South Asian countries are either on a flat or a declining forest area trajectory.

Sundarbans

The Sundarbans is the largest mangrove forests in the world, on the delta of the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers on the Bay of Bengal. The complex network of islands, winding creeks and mudflats provide a home to some of the world’s most endangered species, including the single largest population on Bengal. In a changing climate, sea-level rise, storm-surge intensification, and water salinization will alter the Sundarbans ecosystem significantly, posing threats to both the communities and endangered species that are dependent on it. Compared to when it was first mapped in 1764, the Sundarbans are now barely a third of their original size – and they are continuing to shrink.

A study on the impact of climate change on the Sundarbans ‘ Securing a Resilient Future for the Bangladesh Sundarbans ’ has been supported by the Australian, British, Netherlands, Norwegian, and Finnish governments and the South Asia Water Initiative.

Erosion

Erosion in degraded catchments is a major concern in South Asia. Some of this is natural (e.g., in the central Himalayas) and cannot be controlled asily, but many areas could respond to increased vegetative cover, land management and other nature-based solutions.

Water Stress

The region’s water resources are increasingly stressed.

Global water demand has risen by 600 percent over the last 100 years. By 2050, it is expected that the global water demand will increase by 20-30 percent with growth in industrial and domestic water demand outpacing agricultural demand. In South Asia, water consumption will increase by 16 -24 percent, where the expected significant increases will be in domestic and industrial as an increase in wealth alters diet and consumption. Growing water scarcity and stress underscores the critical need for more effective water management in the region.

Surface water has seen growing threats of over-abstraction and pollution.

It is currently estimated that around 68 to 84 percent of South Asia’s water sources are contaminated. Despite greater government commitments and increased investments for improved water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) over the last decade, the majority of world’s open defecators (610 million) still live in South Asia. Millions still fail to practice good hygiene behaviors. Access to improved water has increased from 73 percent to 93 percent since 1990 in the region. Despite, more than 134 million people still do not have access to improved drinking water (UNICEF). In India the Supreme Court recently expressed grave concern on the over-exploited and critical situation of groundwater in Delhi (India). Excessive pumping in Kabul (Afghanistan) has caused thousands of wells to go dry and the water table is falling at 1.5 meters per year.

In India, 70% of surface water and a growing percentage of groundwater are contaminated by biological, toxic, organic, and inorganic pollutants. Arsenic contamination of groundwater in Bangladesh, which is the source of drinking water for 97% of the population, is considered the world’s largest case of water pollution, affecting approximately 30% of engineered groundwater supplies. In West Bengal, 8 of 17 districts are exposed to arsenic contamination in groundwater. Contamination of drinking water sources by pathogenic microorganisms is also a major issue in South Asia. The source of microbiological contamination is predominantly animal and human waste through defecation, cross contamination from sewer lines, sewage disposal without treatment and seepage from septic tanks. Open defecation is widely practiced in South Asia by more than 300 million people. The nearby graph displays that although sanitation has been on an increasing trend, sanitation that is safely managed and disposed of is negligible. Manufacturing and processing industries also produce large amounts of waste, mostly untreated, into water bodies leading to further pollution. A study by the Indian Central Pollution Control Board finds that nearly 63% of the urban sewage flowing into rivers is untreated. In Sri Lanka, the disposal of unused pesticides, equipment washing, and poor storage have been identified as factors contributing to surface pollution. All of these contaminants can find their way into local water bodies, and subsequently lead to water quality problems.

Source: washdata.org

Water pollution may have adverse economic impacts, including on crop yields. A recent World Bank report studies in detail the adverse impacts of water pollution globally, estimating that water pollution is reducing economic growth in some countries due to detrimental impacts on a variety of sectors, including human health and agricultural productivity. This report notes estimates that biological oxygen demand (BOD) above a threshold can lower GDP growth in downstream areas by 1/3 and by up to ½ in middle-income countries. Other studies have shown impacts on a localized scale. For example, a study of the 63 most polluted industrial sectors in India found that water in these locations are contaminated and that districts immediately downstream of the polluted sites exhibited 9% lower agricultural revenues, driven by lower yields, than districts upstream.

Groundwater depletion has become a major concern in many parts of the region with falling water tables and increased groundwater pollution

South Asia is underlain with substantial groundwater resources (as shown in Figure B3) supported by the major river basins such as the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra. Groundwater abstraction for irrigation has sustained the agricultural economies of multiple Indian states, most notably Punjab, where water-intensive paddy production is significant. With over 20 million wells, South Asia accounts for almost half of global groundwater use for irrigation , and irrigation accounts for more than 80% of groundwater withdrawals in South Asia.

Over-extraction of groundwater not only affects drinking water availability, it also is detrimental for wetlands and rivers. Over-exploitation of groundwater water also affects its quality, by increasing the likelihood of geogenic sources of contamination such as fluoride and arsenic. ~1/4th of Bangladesh’s population are exposed to drinking water contaminated with arsenic due to tapping into shallow aquifers. Arsenic contamination and salinity affect 60% of underground water supply across the Indo-Gangetic Basin, which is a lifeline for a large population in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal, making its water unfit for drinking or for that matter irrigation ( WaterAid ).

Cross-Cutting Challenges

Climate

Looking back, the region’s watersheds exhibit considerable spatial and temporal heterogeneity in its climate.

Afghanistan and Pakistan have the lowest precipitations since mountainsshield them from the monsoons' rainfall. The Himalayan mountains have one of the highest precipitation amounts in the world due to orographic effects. Extreme temperatures can reach as low as –50°C in the Himalayan mountains to 50°C in the Thar desert.

About 80 percent of the rainfall occurs during the monsoon season. The majority falls during the southwest monsoon period from June-September, while the northeast monsoon period from November to March has a lower amount. Maldives rainfall is evenly distributed from April to December. Approximately 75 percent of Afghanistan rainfall occurs as snow from January to March and as precipitation during the spring months from April - June.

South Asia average mean temperature has been increasing at 0.75 °C per century, with the later years shown a noticeable increase. This increase is in line with global temperature trends.

Precipitation in South Asia has shown have shown statistically decreasing trends in most countries with other countries; the trend is weak or with a slight increase as shown in the chart.

Source: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka

The southwest monsoon system has been stable since there are no long-term trends from the year to year variations.

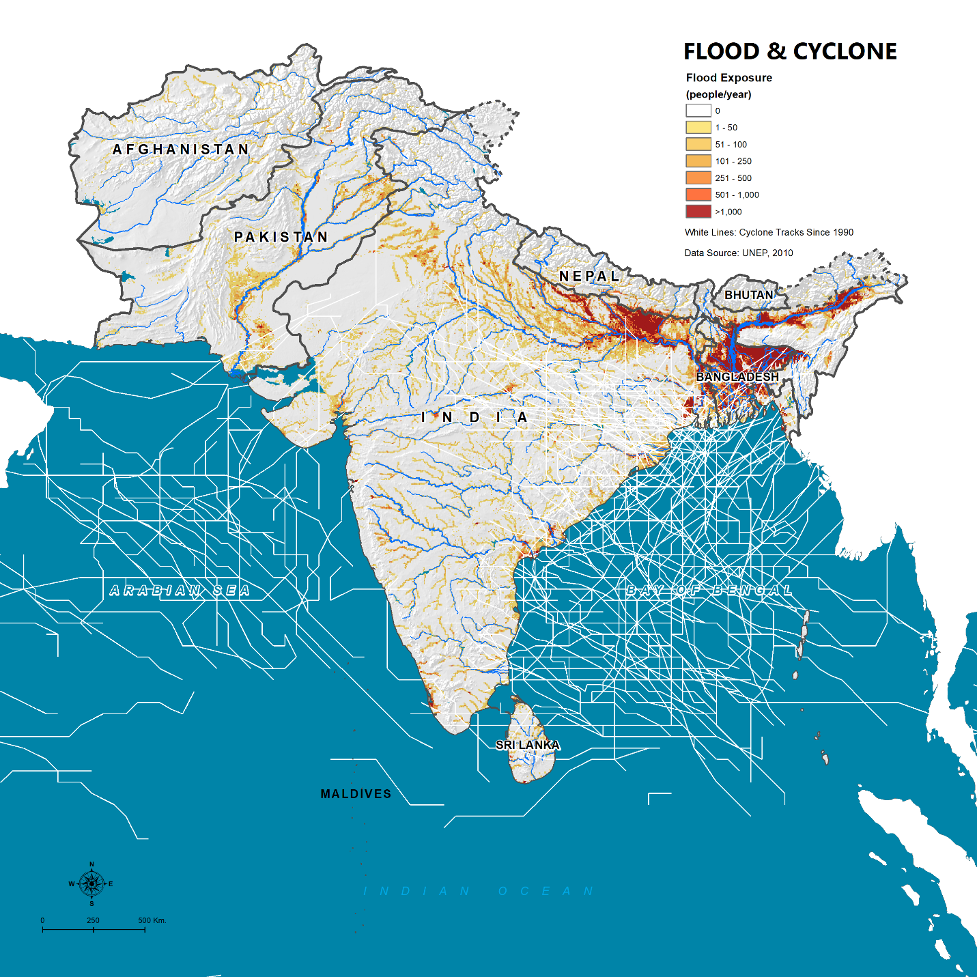

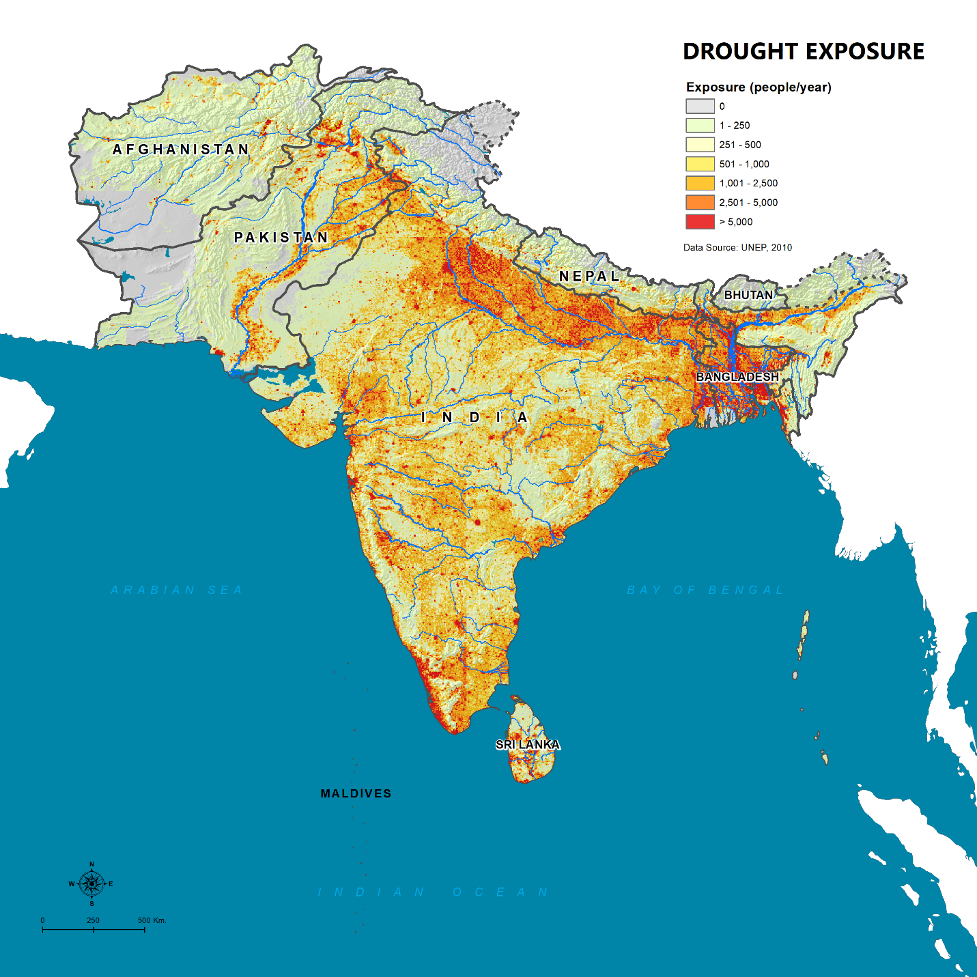

The region is very vulnerable to floods and droughts.

Floods in South Asia expose 50 percent of the world's population to flooding. The number of reported disasters between 2005-2015 was the largest number on record on a decade scale. Damages from floods and droughts have been continuously increasing on a decadal scale as shown in the nearby figures. Each country faces unique challenges. Besides droughts, flooding is also an annual occurrence in Bangladesh where approximately 22-30 percent inundation provides much-needed nutrients to improve crop yields. However, major floodingoccurs when over two-thirds of the country is inundated. In 1998, the flood besieged 70 percent of the country left 25 million people homeless. A Maldives flood event contaminates potable groundwater as ocean water with a high salinity concentration seeps into the aquifer.

Rainfed agriculture, dependent on the vagaries of weather, is particularly susceptible to rainfall variability. Agriculture in South Asia is heavily dependent on rainfall, where 60 percent is rainfed. Although there are different categories of droughts such as hydrological, agriculture, and environmental, it all starts with meteorological droughts where rainfall is below inter-annual averages. Meteorological droughts are likely to occur during ENSO (El Nino) years with the warming of the Eastern Equatorial Pacific Ocean. It has been estimated that half of the severe droughts since 1871 transpire during an El Nino year.

With only four percent of the world's freshwater and 17 percent of the world population, India is extremely vulnerable to the impact of drought as 51 million hectares of it's land is drought prone. With the excessive groundwater pumping in India, usable groundwater may not be available during a prolonged drought. The 1997-2002 drought in Afghanistan impacted 5 million families and caused another million families to migrate to other countries. In Bangladesh, droughts occur on an annual basis that affects three to four million hectares of croplands. Lastly, 1400 reported droughts within twenty years in Sri Lanka have affected 8 million people and 280,000 hectares of cropland.

In addition to rainfall, glaciers are an important water source in South Asia. The Himalaya, Karakoram, and Hindu Kush (HKHK) mountain ranges run 2,400 kilometers through six nations (India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, China, Bhutan and Nepal) and contain 60,000 square kilometers of ice, which is more ice than any other region outside the Poles. The combination of snowmelt, ice melt, and rain from these mountains forms the source of the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra Rivers, and six other large rivers in Asia. Glaciers regulate streamflows within downstream basins, serve as a source of energy, and provide water for direct consumption and agriculture for millions of downstream inhabitants. For example, the more than 750 million people living within the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra basins alone depend on water resources provided by the HKKH mountain ranges.

Within the HKHK, the Indus and Brahmaputra basins have the largest estimated number of glaciers, glaciated area, and ice reserves. The Indus Basin contains over 18,000 glaciers with a glaciated area of over 21,000 km2 and estimated ice reserves of nearly 3,000 km3. The Brahmaputra Basin has over 11,000 glaciers, a glaciated area of 14,000 km2 and estimated ice reserves of over 1,300 km2. ( ICIMOD 2012 ) Both basins are transboundary in nature, and therefore, in addition to sharing the upstream glaciated areas, countries of the HKKH also share the downstream river flows and basin areas. The transboundary Indus River basin has a total size of 1.1 million km2 and is shared by Afghanistan, China, India and Pakistan. Pakistan and India contain the largest area of the basin (52% and 33%, respectively). The Brahmaputra Basin, and Brahmaputra River flows, are shared by China, India and Bangladesh.

Glaciers are threatened by climate change. Climate change is already having a significant impact on the glaciers that store much of the regions water: field, satellite and weather records confirm that nine percent of the ice area present in the early 1970s had disappeared by the early 2000s. Between 2003 and 2009, Himalayan glaciers lost an estimated 174 Gt of water each year and are retreating at a rate of 0.3 to 1.0 meter per year (the most extreme melting occurring in the East), a rate faster than the global average ice mass melt. MODIS snow cover data from 2003 to 2012 show that the Himalayan region has experienced a decline of snow cover area across all elevation belts and aspects.

Rapidly melting glaciers increase the risk of glacier lake outburst floods (GLOFs). Glacial melt contributes to a number of disasters, such as flash floods, landslides, soil erosion and GLOFs. As temperature rises, glaciers begin to melt and recede. The melting creates dams, however, unlike engineered dams which are designed not to fail, these dams are highly erodible. There are two types of dams which are ice dams and the predominant moraine dams that consist of rock and soils from moving glaciers. Morraine dams are more dangerous since they breach very quickly while ice dams have a repeated cycle of drain and fill. Recent research has pointed to an average annual frequency of 1.3 GLOFs since 1980. An increase in GLOF activity could cause significant economic loss. In South Asia, including the Ganges sub basin in China, there are approximately 8,790 glacier lakes, where 203 glacier lakes are considered to be potentially dangerous. Dam breach failures impact lives, crops, infrastructure and hydropower. One study found that damages from potential GLOFs at three glacial lakes in Nepal could be in the billions and Another recent study estimated the value of properties exposed to potential GLOFs at nearly $200 million. One of the largest GLOF’s breach on record is the 1985 Dig Tsho breach in Nepal released 5 million cubic meters of water and the peak discharge was approximately 1,600 cubic meters per second. It destroyed a number of bridges and structures along with a new hydropower plant. It has been estimated that 3 million cubic meters of debris was moved less than 40 km.

Climate Change in South Asia will increase the fundamental challenges to the region’s watersheds. All IPCC models agree that temperatures will rise in South Asia, leading to less snow accumulation, earlier snowmelt, glacier melt, increased crop water demands, and increased system evaporation losses and cooling requirements. Models do not yet agree on the direction or extent of changes in precipitation, but indications are that these changes would intensify the hydrologic cycle, with more dry days, more intensely wet days, and possible fundamental changes to inter-annual to decadal systems such as the annual monsoons that the region depends upon and the changes in more global ENSO systems such as El Nino, La Nina, or the Indian Ocean Dipole. The combined changes could result in significant changes in the hydrology of the region’s streams, rivers, and aquifer recharge as well as the intensity and severity of hydrometeorological disasters such as droughts and floods. The coastal areas of the region’s watersheds would face additional threats of sea level rise, changes in upstream silt transport and deposition (that threaten naturally sinking deltas as the soils consolidate), and increased intensity/frequency of coastal storms that especially threaten Bangladesh and Eastern India.

Data Access

A critical issue that stands in the way of progress on modernizing the way watersheds are planned and managed is the availability of even basic data on these watersheds in the public domain. In some cases, the reason is because the data is not available (e.g. very high resolution elevation data for flood-prone areas or detailed household surveys) but often even the available data is not made accessible due to archaic policies and mindsets. For example, in South Asia, the international transboundary nature of Himalayan watersheds poses additional challenges in terms of bureaucrats and politicians thinking that it is in the interest of national security to keep the data hidden. However, this is not very logical as not only does this then keep it out of the reach of even the national stakeholders that should be reached (e.g. community groups, academia, private sector, etc.) but also in today’s world, there are many other ways to estimate these “secret” datasets especially with old published data, earth observation, and public (or procurable) global data and analytical services.

As accelerating technological progress provides better, faster, and cheaper (incl. free) data and analytic services, there are new opportunities for stakeholders to benefit from these advances. However, more open data access, especially to in-situ and survey information, will allow for improved calibration of models, improved “training” of evolving machine learning algorithms (e.g. for better estimating farm yields or flow forecasts).

Institutional Capacity

Institutional capacity at all levels remains a key challenge in watershed management. This is especially the case both for keeping abreast of the rapidly changing world of new technologies as well as being better connected to evolving global good practices on watershed management.

In the future, improved automation and new technologies could change the nature of capacity-building required.

Capacity is also a significant constraint at local stakeholder level – e.g. at village or district levels, where it is required for local coordination, consensus-building, and decentralized management of water using the principle of subsidiarity where possible. Adequate empowerment of all sections of society in transcending traditionally-divisive issues such as gender, religion, caste, economic class, education levels, politics, and other factors remains a significant challenge in many communities.

Transboundary Collaboration

A particular challenge in some parts of South Asia, especially the large basins that emerge from the Hindu-Kush Himalayas (e.g. Indus, Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna), consist of areas in the jurisdictions of different countries (and also some disputed territories). This poses additional problems in terms of data access/exchange and coordinating investment planning and operations in a coordinated systems context. Some of these have implications even beyond the South Asia region – e.g. China is part of the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra basins and some of Afghanistan’s basins have other connections with countries of Central Asia, Iran, etc.

The South Asia region, unlike many other regions, is not a region with many effective river basin organizations at both transboundary levels or even within nations. This leads to additional challenges of working across sectoral boundaries as well as trans-boundary administrative boundaries within countries where conflicts are emerging (e.g. Basins like the Cauvery shared across four southern states of India).