Overview

Land degradation is the loss of land productivity across a range of sectors, such as economic and biological productivity. Land degradation leads to desertification, biodiversity loss, and the loss of soil health upon which agriculture depends. The world is losing 100 million hectares of land each year due to land degradation with significant and deleterious impacts to people (see box below).

Key Facts about Land Degradation Globally

- 3.2 billion people globally (and 40% of the world’s poorest) are impacted by land degradation.

- 50 million people may have to migrate over the next 10 years due to desertification.

- 6 out of 10 people live in areas that experience water stress for some of the year.

- 40% of local conflicts globally from 1946 to 2008 were triggered by natural resource use issues.

Source:The World Bank

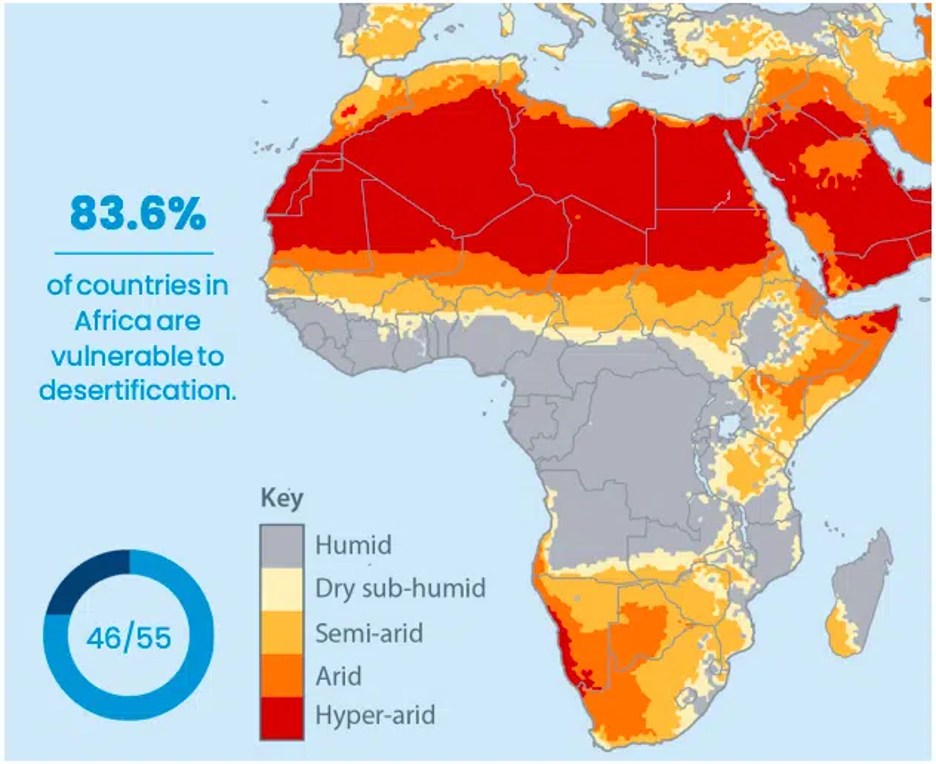

The Sahel is highly vulnerable and is indeed already intensively experiencing land degradation. The landscape of the Sahel comprises a mostly flat topography of savannah and grasslands with a tropical semi-arid climate marked by low and variable levels of precipitation and high temperatures. The semi-arid landscape of the Sahel is highly vulnerable to social, economic, and environmental changes and disruptions, especially because of the importance of the agricultural sector and its reliance on rainfall for productivity. Most annual precipitation is delivered in several months during the summer, with the rest of the year mostly dry. For this reason, desertification – caused by unsustainable land use practices in the agricultural sector, overpopulation, and naturally occurring levels of soil erosion – is a major threat to the long-term health and well-being of the Sahel region and its population.

This section presents climatic, environmental, economic and social challenges in the Sahel region that are drivers and consequences of land degradation in the region.

Climate Related Risks

Climate-related risks in the Sahel region include climate variability and change, water resources and scarcity, and disasters such as droughts and floods.

The climate across Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger exhibits significant variability, characterized by a strong north-south gradient. Conditions range from hyper-arid Saharan deserts in the north to semi-arid Sahelian zones, transitioning into tropical savannas in the southernmost regions. Precipitation across the G5 Sahel varies dramatically, from less than 50 mm annually in much of Mauritania to around 776 mm in parts of Burkina Faso. These differences result from seasonal shifts of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and proximity to the Sahara Desert.

Each country experiences one rainy season, with northern areas receiving notably less rainfall than southern regions. Harmattan winds blowing from the Sahara further reduce rainfall, particularly in Mauritania, Niger, Chad, and northern Mali. Chad’s annual precipitation ranges from nearly zero in the north to about 1,200 mm in the south; Mali varies from less than 150 mm in the north to 1,400 mm in the far south; Niger receives between 150 mm in northern areas and up to 800 mm in the south. Burkina Faso generally receives between 500 and 1,000 mm of rainfall annually.

The World Bank’s recent CCDR for the Sahel estimates that climate change could have a significant impact on Sahel countries, especially in the dry and pessimistic climate scenarios, under which countries like Burkina Faso and Niger could experience reductions in annual GDP of almost 7% and 9% by 2050, respectively.10 The CCDR notes that these impacts are likely underestimates because they do not account for the impacts of climate change on migration, conflict, and ecosystem change that will also impact GDP eventually.

Precipitation varies widely in the G5 Sahel from 91.9 mm of rainfall in Mauritania to 776.3 mm of rainfall in Burkina Faso, which is highly influenced by the Intertropical Convergence Zone, and its near location to the Sahara Desert. The ICTZ follows the sun by moving north during the summer, and south for the northern hemisphere winter. The Sahel region lies about 10°N, where there is very little rainfall for one rainy season. Countries to the north such as Mauritania and Niger experience little rainfall, while Burkina Faso receives substantially more rainfall. In addition, the dry Harmattan winds from Sahara Desert will decrease the precipitation in Mauritania, Niger, Chad and northern Mali. Click on the countries to explore the annual precipitation.

The G5 Sahel region experiences consistently high temperatures throughout the year, averaging monthly temperatures above 25°C. Maximum heat occurs from March to July, when temperatures reach the mid-30s Celsius, with peaks of about 33°C in Mauritania during June or July and up to 35°C in Mali. Lower temperatures occur from November to March due to cooler, dry air brought by the Harmattan winds. Cooler conditions are found in central Burkina Faso and mountainous regions of Niger. Chad’s central and northern regions experience significant seasonal temperature fluctuations, ranging from 20–27°C in winter to 27–35°C in summer, while Mali experiences cooler months from October to February, reaching temperatures around 24°C.

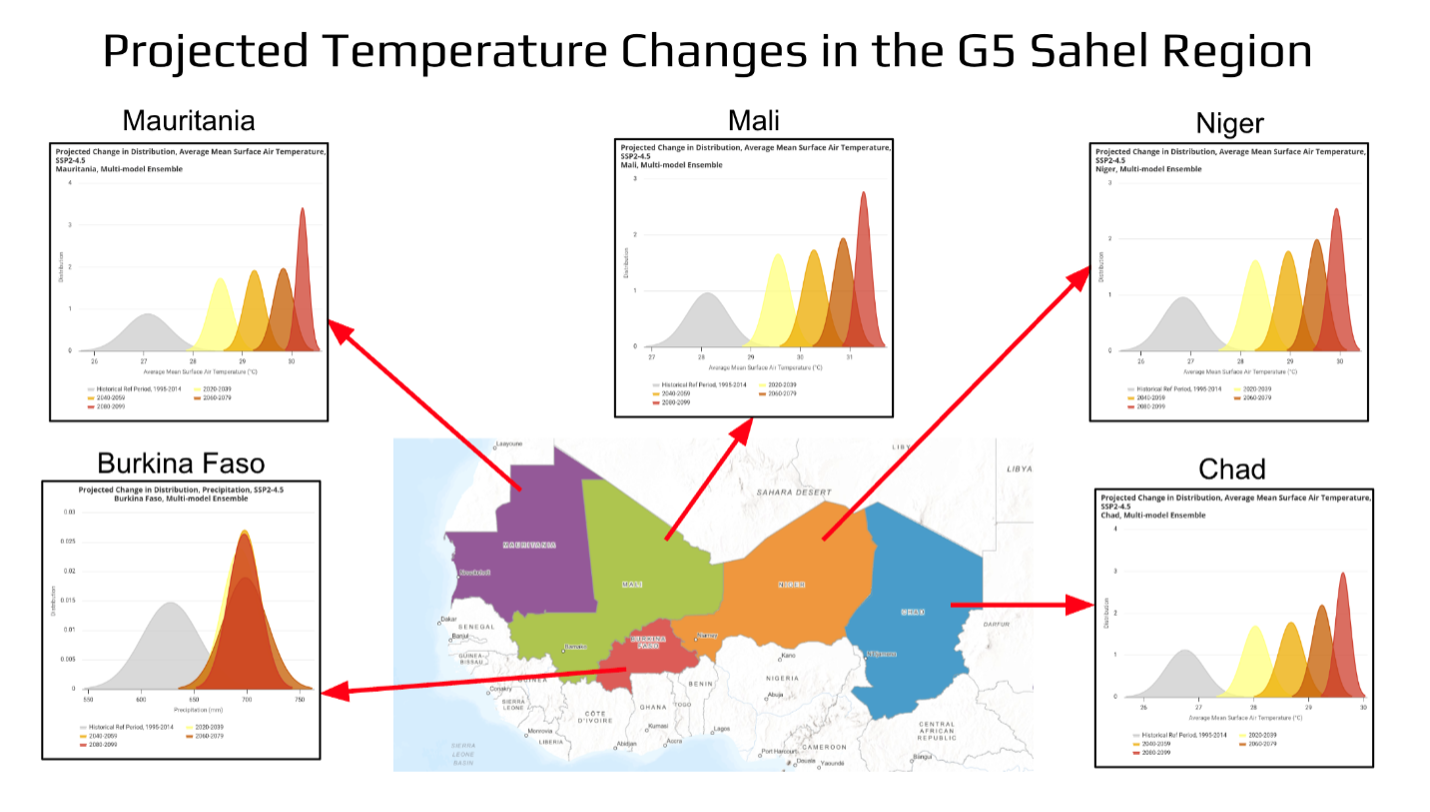

Annual temperatures for the G5 Sahel can be explored further in the attached figure.

While the countries of the Sahel contribute little to climate change – producing than 1% of global emissions - climate change models suggest that average temperatures in the Sahel could increase by up to 3°C by 2050, placing more than 13 million more people into poverty in the region.

Climate change will likely have significant economic impacts on Sahel countries, especially under drier and more pessimistic scenarios. Burkina Faso and Niger could face annual GDP reductions of nearly 7% and 9%, respectively, by 2050 . These projections underestimate the overall impact as they don’t account for climate-induced migration, increased conflict, or ecological disruptions (World Bank, 2020).

Projected temperature is to increase by 2 to 4°C across the G5 Sahel countries by 2100 under SSP2-4.5, as shown in the map and inset charts.

Source: CCKP

Water Resources and Scarcity

Water resources in the region exhibit spatial and seasonal variability. Perennial rivers, such as the Niger and Senegal, are transboundary basins, while Lake Chad, also transboundary is an endorheic freshwater lake (no outlet). Ephemeral streams flow only briefly during and after precipitation events. Groundwater serves as the primary water source, especially in rural areas, for drinking and livestock needs.

Total renewable water resources in the Sahel vary widely, from 600 m³ per person in Burkina Faso, sourced almost entirely from internal runoff, to over 5,200 m³ per person in Mali, which has abundant internal resources. In contrast, Mauritania, Chad, and Niger rely heavily on transboundary inflows.

Despite substantial renewable water resources in most Sahel countries, actual water use per person remains low, as water is not available year-round or where the population resides, as shown in the nearby figure.

The nearby chart shows water demand by sector, with agriculture as the major user, ranging from just over 50 percent in Burkina Faso to more than 90 percent in Mali, Mauritania, and Niger.

Surface Water

Transboundary water is vital for development of the Sahel since water bodies cross national boundaries and support livelihoods and economies.

The Niger River, originating in Guinea near the Sierra Leone border, flows northeast through Mali, forming the Inner Niger Delta. It continues through Niger and along the Benin border before entering Nigeria. The river is vital for drinking water, agriculture, fishing, and transportation for the populations along its course.

Niger River Basin

In the west, the Senegal River, headwaters are also in Mali and Mauritania, which supports agriculture, fisheries, energy production, and water transportation.

Senegal River Basin

Lake Chad is also critical for the area as it supports agriculture, fishing, and livestock herding and is used for water transportation.

Lake Chad Basin

Over 7,000 years ago, the Lake Mega Chad used to cover over 400,000 Km 2 (larger then any lake existing globally today) – the modern Lake Chad is a mere fraction of its former size and the Lake has further shrunk 90 percent from 1960s due to population growth, climate change and an increase in irrigation.

The google time lapse video shows a decrease in water surface area over time.

Groundwater

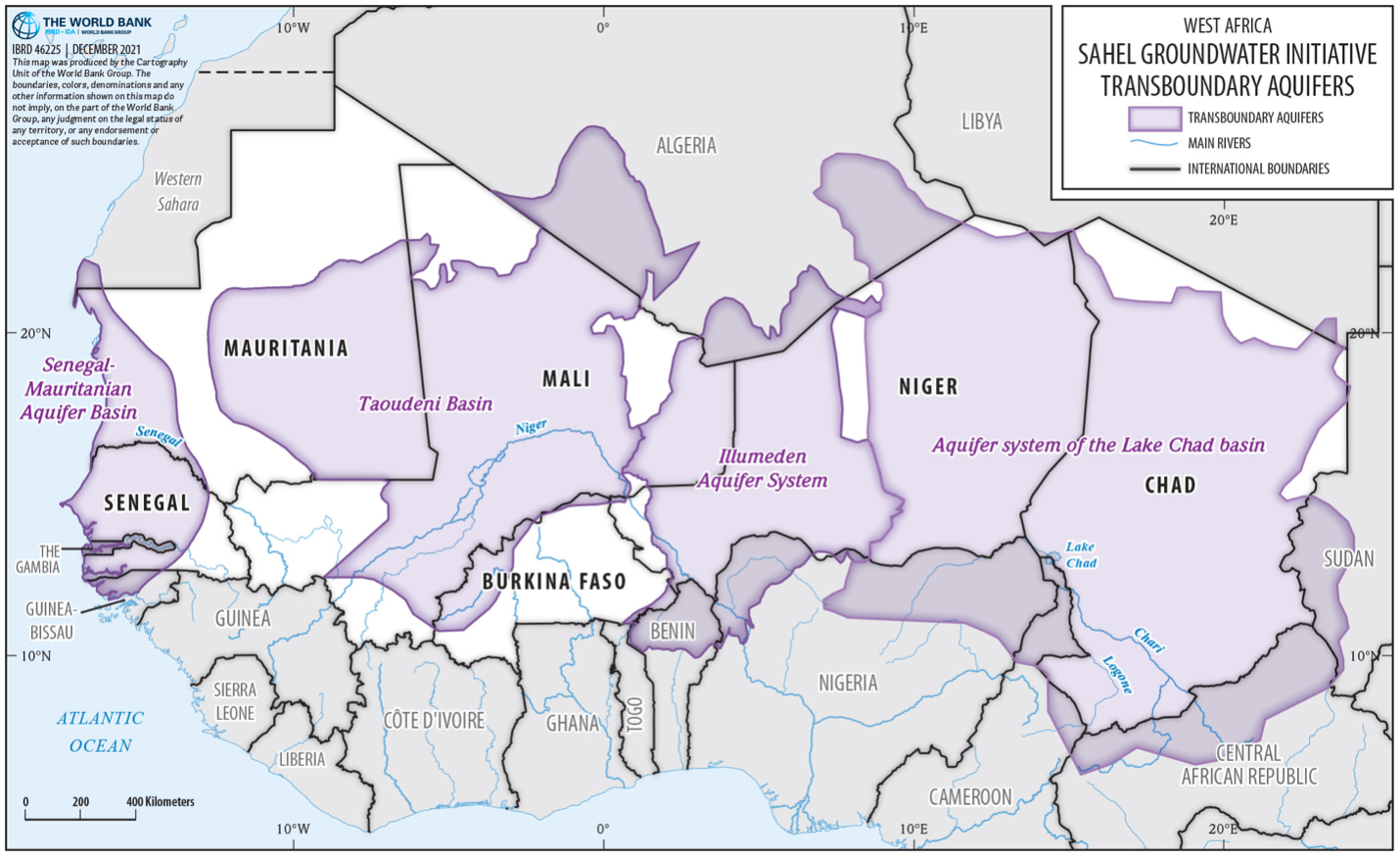

Groundwater is the main source of water for about 100 million people in the Sahel region , where rivers and lakes are scarce. The G5 Sahel countries have four major groundwater basins: the Senegal–Mauritanian Aquifer Basin, the Taoudeni Basin, the Iullemeden Aquifer System, and the Lake Chad Basin Aquifer. These basins typically have low infiltration rates, but recharge rates vary significantly. For example, in the Lake Chad Basin, recharge rates range from 78 ± 7 mm per year in the Sahelian catchment to up to 240 ± 170 mm per year in the more humid upstream areas .

Ground Water Resources in the Sahel.Source: World Bank

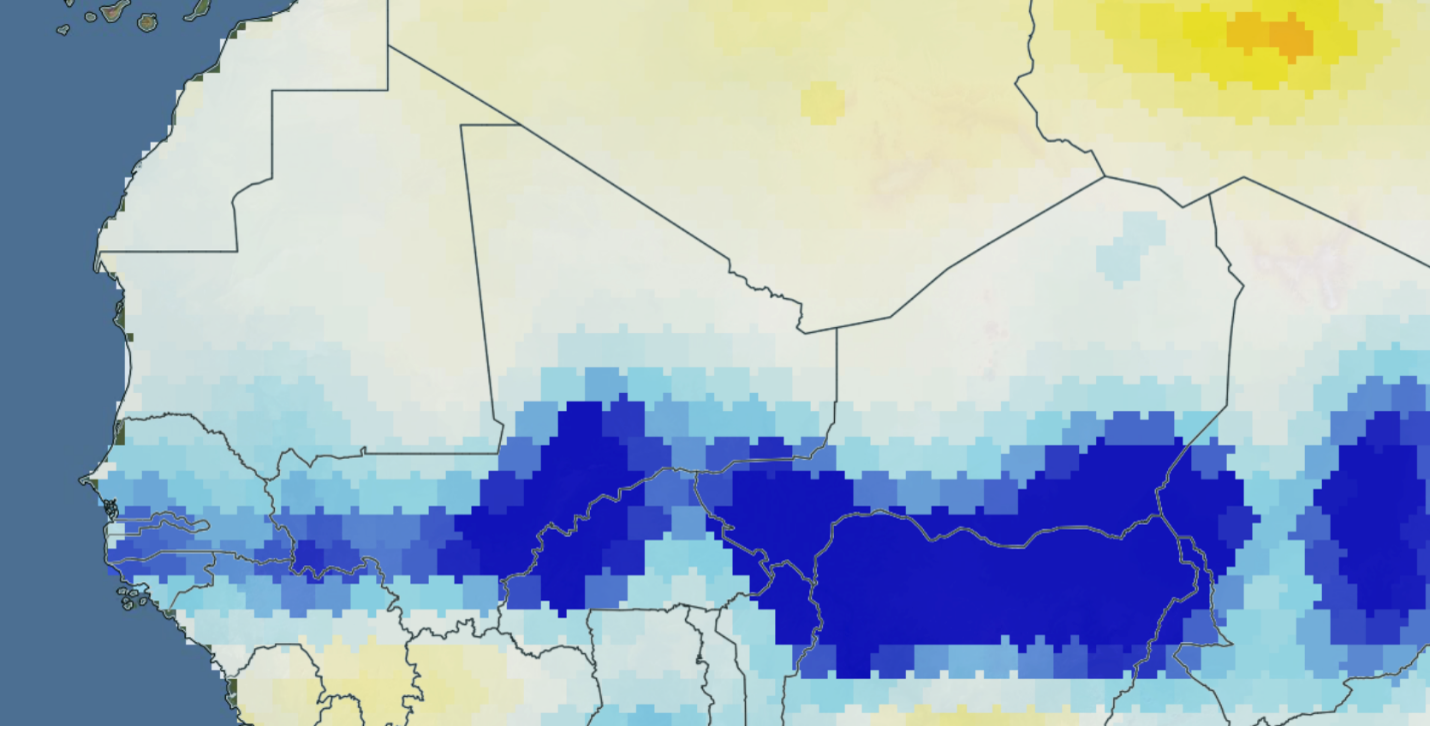

NASA GRACE Recovery and Climate Experiment measured groundwater change using satellite data. From the observed map, groundwater levels are generally increasing in the southern areas of the country.

Water Infrastructure

Hydraulic infrastructure in the region supports the management of scarce water resources for agriculture and drinking water. Dams are utilized for irrigation, hydropower, flood control, and water supply. Burkina Faso has the highest number of reported dams, totaling 123 as shown in this interactive chart. While Chad has no dams listed in major databases, numerous small-scale dams exist throughout the region but are often undocumented. To increase water resilience, Mauritania operates two small desalination plants in Nouadhibou and Nouakchott. Burkina Faso also reclaims wastewater for urban agriculture, mining, and sanitation. However, similar practices in other countries remain limited or unrecorded. Water treatment and sanitation infrastructure is sparse, underscoring the need for improved data collection and investment to strengthen water resilience across the region.

The locations and details of dams and wastewater treatment plants can be further explored through the Sahel web map.

Disasters

Droughts and floods are the main natural hazards in the region. Droughts affect many people because they can span multiple regions and even cross borders. Floods are more localized, occur more frequently, and outnumber other natural hazards in the area. The number of people affected by natural hazards can be explored further through this interactive graphic.

Droughts

The three-month Standard precipitation index from the Copernicus Drought Observatory reveals moderate dryness and wetness throughout the region.

Floods

The 100-year Flood Hazard map from CDRI reveals the risk of riverine flooding under current climate conditions. Flood exposure is in the Niger River in Mali and the Lake Chad area.

The economic impact of floods is broken down by sector where existing buildings are associated the greatest infrstructure loss.

Environmental Drivers

A number of interlinked environmental drivers are responsible for land degradation in the Sahel.

Desertification

Desertification is a process through which fertile, arable land converts to desert. Desertification is land degradation in drylands This process can be driven by a range of factors, including deforestation, overgrazing and/or farming, and drought. Bordering and encroaching on the Sahel, the Sahara desert is growing around 48 km annually The video below shows how the Sahara desert has grown over time. Impacts of desertification include loss of arable and fertile soil, loss of biodiversity and vegetation, food insecurity, water scarcity, and loss of economic productivity.

Source: Earth.Org

Deforestation and Overfishing

Forestry and fisheries are vital to the economies and livelihoods with forestry holding significant potential for a green economy and fisheries contributing substantially to national GDP and export earnings, particularly in Mauritania where it accounts for 4-10% of GDP and 35-50% of exports. About 73% of Burkinabé and 68% of Mali’s workforce were employed in agriculture, forestry, or fishing in 2021. Inland fisheries in Mali, particularly along the Niger River and Lake Débo, are essential livelihoods, providing income and nutrition for thousands of households.

Despite the importance of forests and fisheries, deforestation and overfishing reflect unsustainable resource use that drives land and resource degradation. The Sahel lies in an arid region; thus, forests are extremely sparse. Forest cover in the G5 Sahel is among the lowest in the world, only about 0.3% of land in Mauritania is classified as forest, Niger has under 1% forest cover (down from ~1.5% in 1990) , while the relatively wetter southern Sahelian countries have modest forest area: Mali has about 10–11% of land under forests, Chad ~9% , and Burkina Faso ~22% . Deforestation is a significant problem in the region, where trees are cut for firewood and to clear space for agricultural production. Overfishing is depleting fish stocks across the region as well, such as in Lake Chad.

Burkina Faso

Chad

Mali

Mauritania

Niger

Biodiversity and Biodiversity Loss

The ecosystems of the Sahel derive from a relatively dry climate with a rainy season, and include grasslands, woodlands, and savannah and patches of wetlands and streams.The Sahel region is home to various large and medium-sized mammals, uniquely adapted to extreme heat, low prey density, and scarce water availability. Notable mammals inhabiting this landscape include the African Savanna elephant, African forest elephant, Saharan cheetah, African lion, Leopard, Hippopotamus, Dama gazelle, Barbary sheep, Dorcas gazelle, Addax, Scimitar-horned oryx, Striped hyena, African wild dog, among others.

The Sahel also serves as a critical habitat for resident and migratory bird species, providing a flyway for birds moving between Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa. Resident birds, such as the Arabian bustard, Nubian bustard, and African fish eagle, are commonly observed in this region. Bustards typically inhabit dry grasslands and are known for their cryptic plumage and ground-dwelling behavior, while the African fish eagle is associated with Sahelian wetlands and rivers. Migratory bird species that winter in the Sahel include the Common ostrich, Peregrine falcon, European roller, Montagu’s harrier, Red-billed quelea, Rueppell’s Griffon, White-backed vulture, hooded vulture, Great grey shrike etc. Many of these species, such as the shrike, are trans-Saharan migrants that breed in Europe before traveling to the Sahel during the winter.

Reptiles in the Sahel are well-adapted to harsh climatic conditions, exhibiting burrowing or nocturnal behaviors to cope with high temperatures and aridity. Common reptile species include the Saharan horned viper, Senegal flap shell turtle, African spurred tortoise, Nile Monitor, Nile crocodiles and Slender-snouted Crocodile. The horned viper is well-camouflaged in sandy environments, while the African spurred tortoise is one of the largest tortoise species, which survives prolonged droughts through burrowing. The Nile monitor lizard and crocodile were reported along rivers and wetlands. Several species of vertebrates found in the Sahel region were reported under the IUCN Red List of Threatened species in various threat categories: Critically Endangered (CR): African forest elephant, addax, White-backed vulture, hooded vulture; Endangered (EN): African Savanna elephant, African wild dog, Chimpanzee; Vulnerable (VU): African lion, Cheetah, Leopard, hippopotamus, Barbary sheep, Dorcas gazelle, African spurred tortoise, Senegal flap shell turtle, and Slender-snouted Crocodile; Near Threatened (NT): Striped hyena, Arabian bustard, Nubian bustard; Extinct in Wild (EW): Scimitar-horned oryx.

Importantly, the Sahel region supports many endemic species, meaning species that are not found elsewhere in the world, including endemic plant, rodent, reptile and bird species (IUCN 2017).

Biodiversity Loss

The Sahel region is experiencing rapid and widespread biodiversity loss driven by environmental, socio-economic, and governance-related factors. The region's fragile ecosystems-spanning savannas, drylands, wetlands, and coastal zones are increasingly threatening the survival of unique species. Climate change, habitat destruction, and unsustainable resource exploitation are the most critical drivers. Rising temperatures, erratic rainfall, and frequent droughts alter habitats and reduce ecosystem resilience. Demographic pressures have led to overhunting, poaching, and overfishing. Weak environmental governance, limited financial resources, and inadequate scientific infrastructure further constrain conservation efforts across the region. This has caused researchers to recommend additional protected areas in the region to protect existing biodiversity.

In Burkina Faso, biodiversity is threatened by rapid deforestation, the shrinking of freshwater bodies and wetlands, and the degradation of agricultural land due to drought and unsustainable land use. In Chad, biodiversity loss is driven by desertification, deforestation, land clearing, and overexploitation of natural resources. Poorly managed pastoral systems and invasive species disrupt native ecosystems. Harmful fishing practices and pollution from mining and petroleum activities severely threaten aquatic biodiversity. Mali faces a biodiversity decline due to agricultural expansion, urban sprawl, bushfires, overgrazing, and the unsustainable extraction of forest products. Habitat fragmentation, soil erosion, invasive species, and extractive industries (mining and oil) compound the threats, particularly in terrestrial and coastal-marine ecosystems. In Mauritania, overgrazing, overharvesting of forest resources, poaching, and habitat fragmentation are key drivers of biodiversity loss. Additional threats include bushfires, urban expansion, and the spread of invasive species. Mining and oil activities contribute to land degradation and pollution. Coastal and marine ecosystems are endangered by overfishing, the use of destructive fishing gear, and sea-level rise, which impacts sensitive habitats such as coral reefs and seagrass beds. In Niger, the loss of biodiversity stems from poor agricultural practices, habitat degradation, overexploitation of wildlife, and pollution. Natural threats such as declining rainfall, droughts, and extreme temperatures further erode ecosystem health.

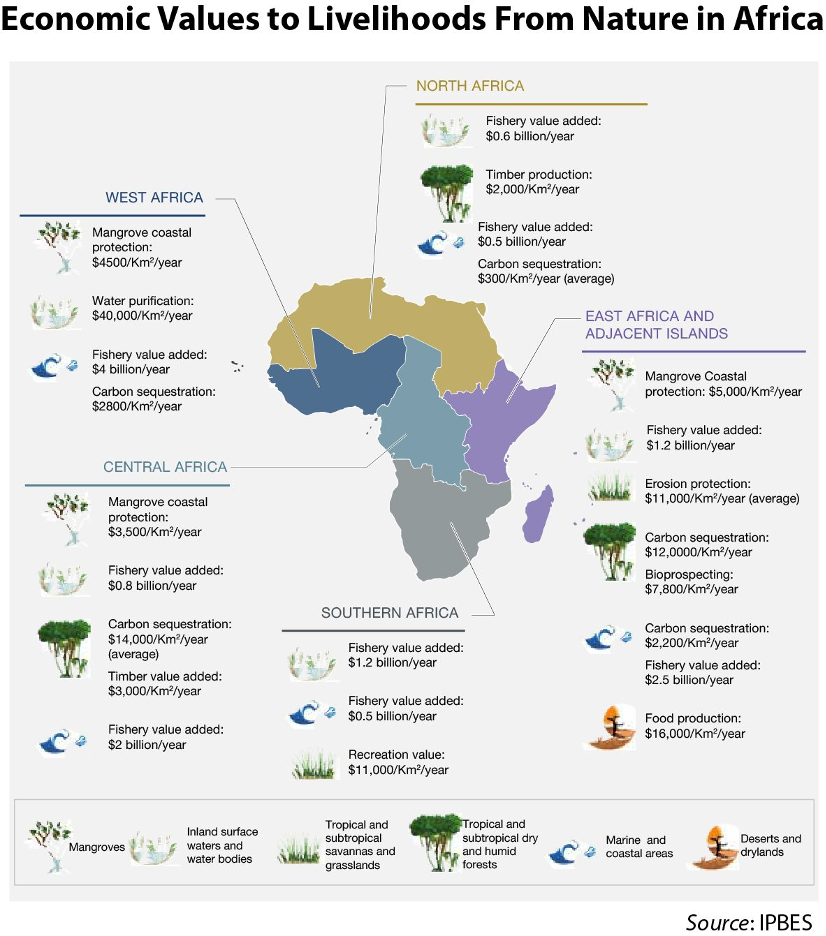

The loss of biodiversity has significant impacts to humans given the value of this nature. The figure below illustrates the economic values to livelihoods from nature in Africa, showing the ecosystem services values in West Africa associated with mangroves, trees and vegetation, and species.

Invasive Species and Pests

Invasive species and pests can lead to biodiversity loss as well, as invasive species with few local predators are able to root and multiple faster than native species, thereby outcompeting natives with subsequent impacts to food chains and ecologies. In the Sahel, notable invasive species are Sahara mustard and the black rat. Invasive plants may impact protected areas in West Africa (IUCN 2013.

Pollution

Pollution in recent years has become a challenge driven by rapid urbanization, weak waste management, and climate pressures. Air pollution from dust storms, biomass burning, and outdated vehicles affects cities like Ouagadougou and Bamako, where PM2.5 levels often exceed WHO safety thresholds (WHO, 2023). Water sources are increasingly contaminated by untreated domestic waste, agrochemicals, and poor sanitation systems, contributing to cholera and diarrheal outbreaks, particularly in Chad and Niger. Poor Solid waste management causes waste accumulation, especially plastic waste in urban areas due to low collection rates—often below 50%—and open dumping, worsening flood risks and environmental degradation.

Economic Drivers

Rural communities in the Sahel region rely on agriculture, livestock rearing, fisheries, and natural resources for their food and nutritional security. Agricultural activities in the Sahel include the cultivation of staple cereals such as millet, sorghum, rice, maize, wheat, barley, and fonio, along with cash crops like cowpea, groundnut, onion, sesame, sorrel, tomato, and cotton. Date production has emerged as a valuable economic activity. Livestock commonly reared include cattle, sheep, goats, camels, donkeys, horses, and poultry. The region's diverse grass species support grazing for livestock, while fish from rivers and wetlands serve as a critical source of protein for local diets.

Except for Mauritania, the G5 countries of the Sahel are low-income in terms of average per capita GDP – US $790 in 2021. Further, over 30% of the population in the G5 countries are below the international poverty line.3 The population is heavily dependent on agriculture – half of all employment is delivered by this sector – making employment in the region highly vulnerable to disruptions caused by climate and climate change and other challenges such as conflict and population displacement.

Agriculture & Irrigation

Agriculture is the backbone of the G5 Sahel countries, it accounts for 40% of GDP, the sector employs a majority of the workforce in the region. According to the Sahel Alliance 5-year analysis results report, productivity in this sector remains low, and current agricultural output often fails to meet the needs of the region’s rapidly growing population. This is in part due to over 90% of farms depending on rain-fed cultivation, with less than 1% of cultivated land depending on irrigation, thus agriculture in the region is highly susceptible to drought and climate vulnerability. Lack of water and land degradation affect 80% of the population living in arid or semi-arid areas.

Selected Irrigation Indicators in the Sahel Region (Data Source: World Bank )

Social Drivers

Population

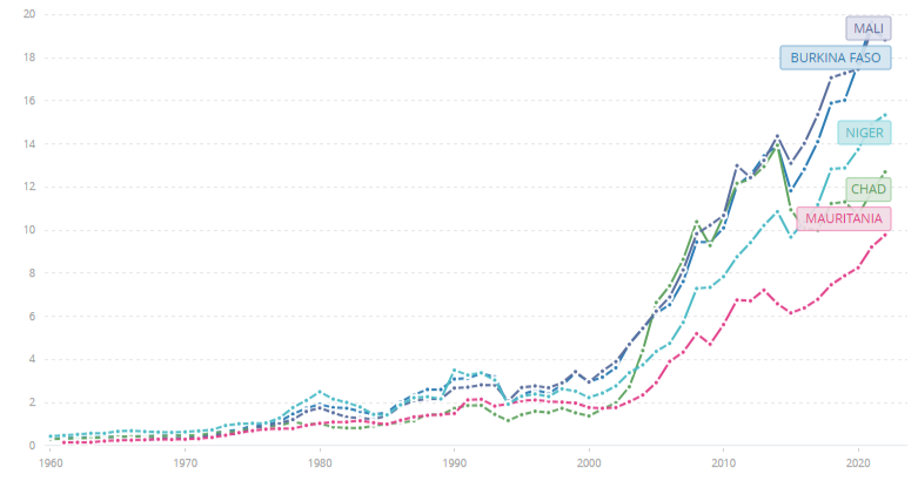

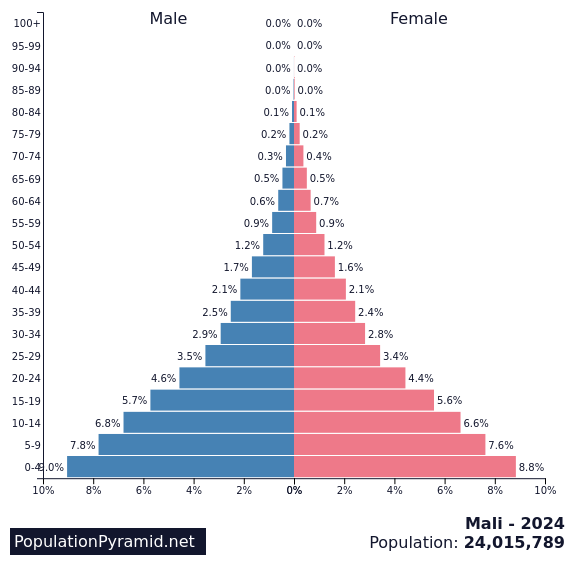

The G5 Sahel countries are home to 89 million people , with population growth rates higher than in any other part of the world. The population in the region grew from 17.3 to 86.4 million between 1960 and 2020. It is projected that the population will rise to between 180 and 211 million by the year 2050.

The G5 nations are home to 89 million people , with population growth rates higher than in any other part of the world. The population in the region grew from 17.3 to 86.4 million between 1960 and 2020. It is projected that the population will rise to between 180 and 211 million by the year 2050. high fertility rates, ranging from 4.6 children per woman in Mauritania to 7 children per woman in Niger —the highest globally.

Nevertheless, the region's overall population density remains relatively low compared to other parts of Africa, with Burkina Faso having the highest density at 35 people per square kilometer, and Mauritania among the lowest worldwide at just 4 people per square kilometer.

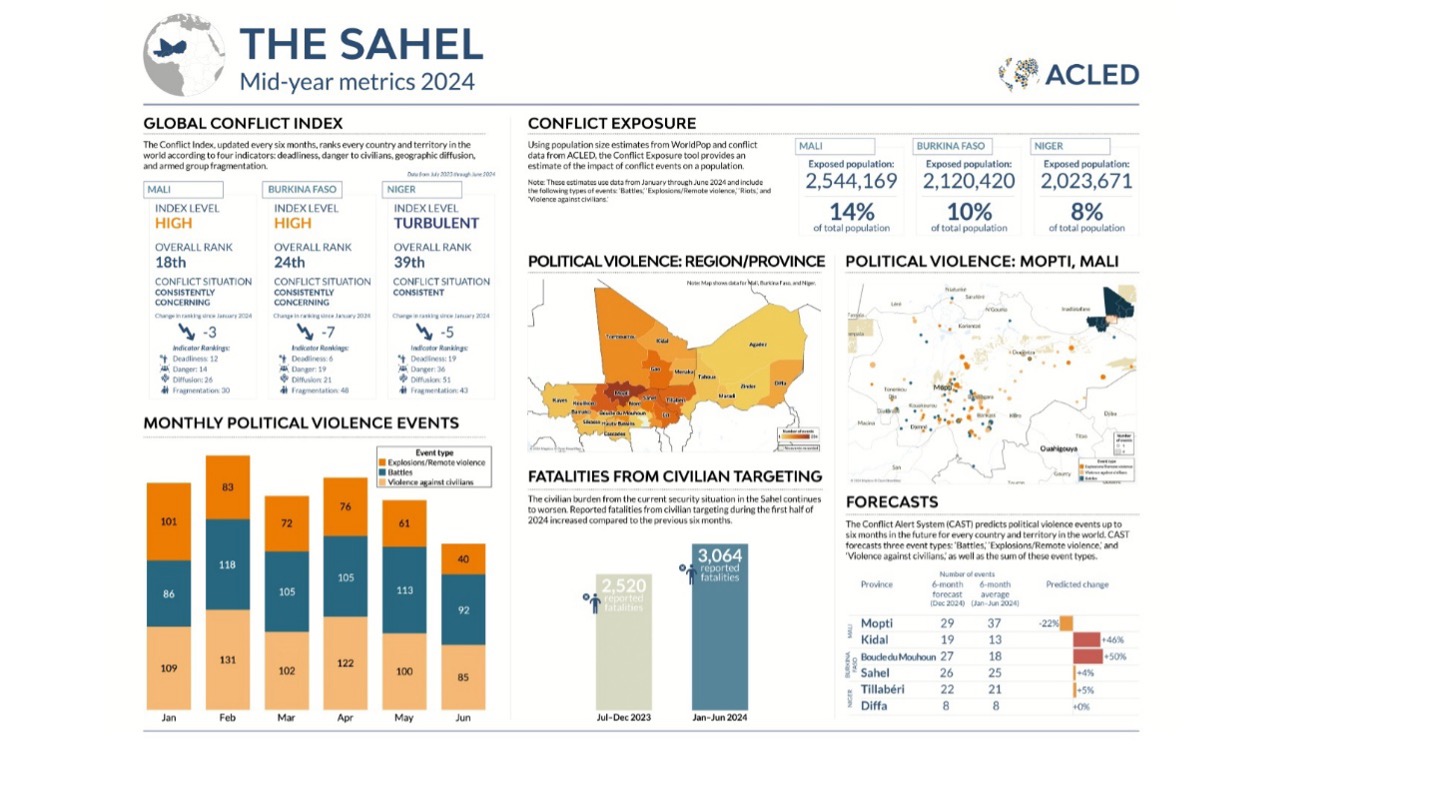

Conflict

The G5 Sahel countries have experienced over 30 military coups since gaining independence in the 1960s. As of mid-2024, the region continues to experience high levels of conflict and violence, with significant civilian fatalities, extensive political violence, and millions exposed to conflict events, particularly in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. These ongoing conflicts are driven by several factors, including the expansion of violent extremist groups, inter-communal tensions often exacerbated by resource scarcity and climate change, and the varying effectiveness of national responses. Such instability has resulted in widespread displacement, humanitarian crises, and significant development challenges, necessitating a multifaceted approach to peacebuilding and stabilization efforts.

A mid-2024 snapshot of conflict trends in the Sahel, highlighting political violence, civilian impact, and regional instability across Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger .(Source: ACLED )

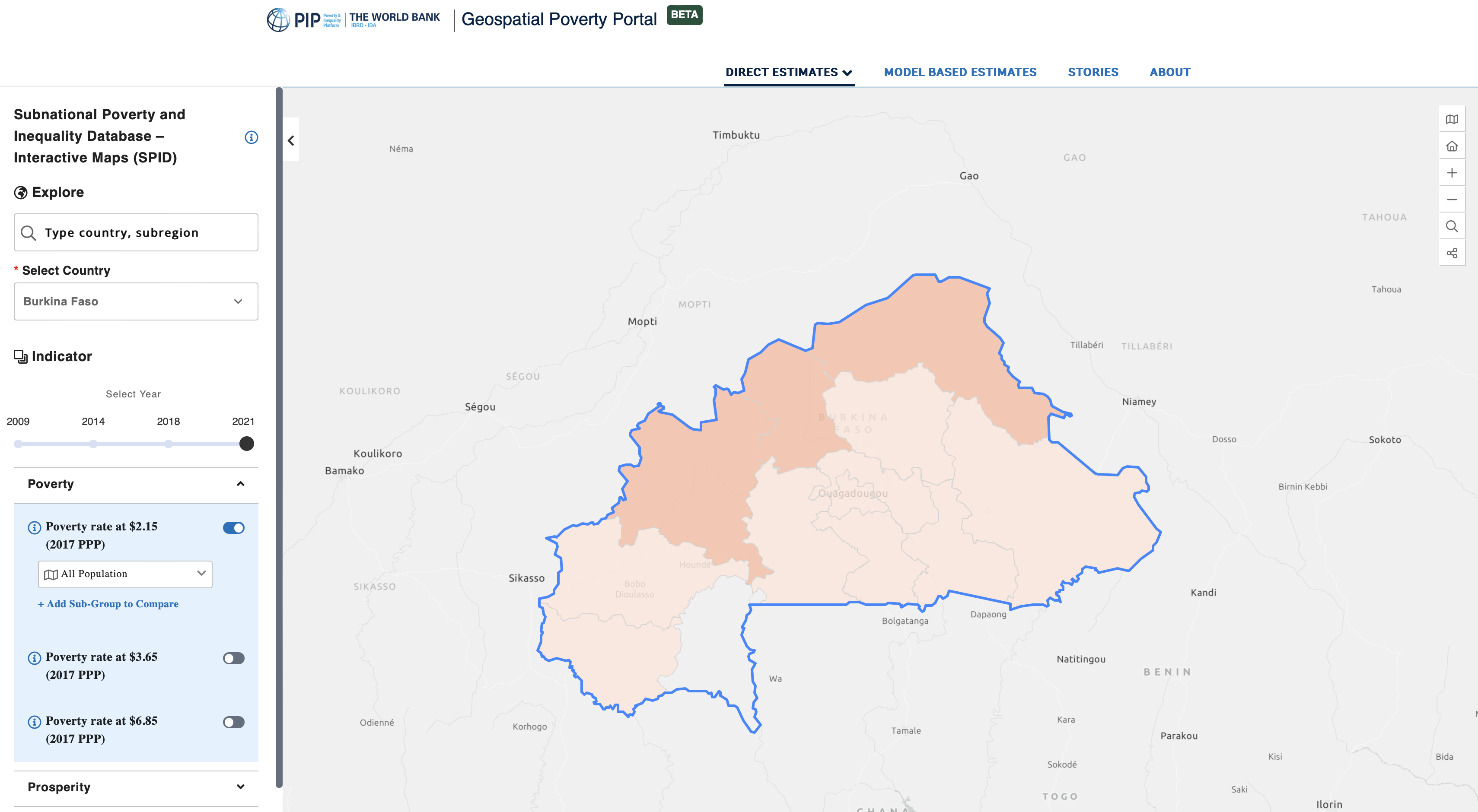

Poverty & Livelihoods

Poverty remains pervasive, with approximately 40–50% of their populations living below the international poverty line in the region. in Niger , the extreme poverty rate was 45.3% in 2024, projected to decline to 35.8% by 2027. Similarly, Mali's poverty rate increased from 42.5% in 2019 to 44.4% in 2021, pushing an additional 375,000 people into extreme poverty. Livelihoods in these countries heavily reliant on agriculture, pastoralism, forestry, and fisheries, sectors extremely vulnerable to climate-related shocks, such as drought and land degradation.

Food Insecurity

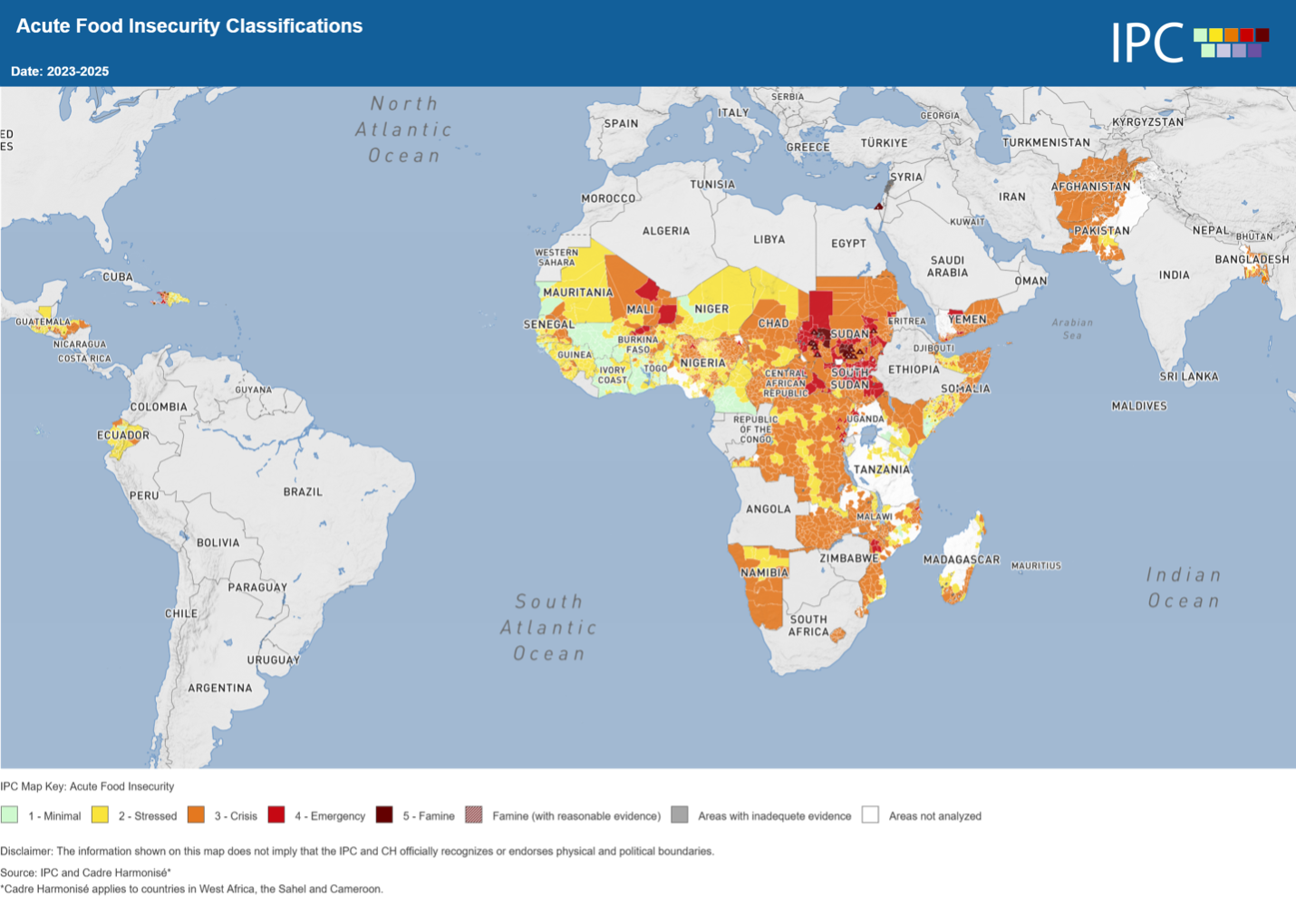

There is severe food insecurity in the Sahel, fueled by climate change impacting fragile agriculture and pastoralism. Ongoing conflict disrupts food systems, displacing people and limiting aid. These factors combined with poverty and rapid population growth, leave millions hungry, demanding urgent action to build resilience, ensure stability, and improve humanitarian access. It is estimated that in five countries 10.2 million people were food insecure from June to August 2023( millions in the G5 Sahel are in “Crisis” or worse (IPC Phase 3+)during each lean season (the pre-harvest hunger period)). Out of these, more than 900,000 people were in emergency situations, and in Burkina Faso and Mali more than 45,000 people faced famine.

Map of Acute food insecurity classifications globally, 2023-2025 (Source: IPC)