IWRM in a Bhutan Context

Key Water Security Challenges

Water security related issues and challenges may be grouped into following categories:

Spatial and temporal variations in water availability

Water availability and accessibility in Bhutan is largely influenced by the topography and seasonal variations in precipitation. Because of the rugged terrain, much of the water resources are either in the form of solid glaciers, ice, and snow in higher uninhabited elevations or flowing in deep gorges and valley bottoms while communities are largely settled along the slopes. This makes availability of water resources highly variable across the country I.e., too much in valley bottoms and scarcity along slopes.

The above situation is further exacerbated by variations across the four seasons. Bhutan has four seasons with rainfall pretty much concentrated in summer/ monsoon season while Winter, Spring and Autumn seasons have extremely low precipitation.

The above spatial and temporal aspects of water availability create a situation of too much water where and when it is not required and sometimes less in areas and times where it is required most. This impacts the reliability of water supply for growing urban areas and especially for agriculture that consumes most of the water in Bhutan. This situation is exacerbated in dry years and is expected to get more challenging as temperatures warm and rainfall gets more uncertain in future decades as climate change impacts are increasingly manifested.

Management challenges

Water resources that are accessible for human use is further confronted with management issues. The common management challenges arise from:

Water as Common Pool Resources (CPRs)

In economics, water resources are generally categorized as CPRs owing to its nature as free flowing, vulnerable to depletion and degradation from use. Because of the free-flowing nature of the resource, it is difficult to keep water resources away from users while utilization of the resource results in depletion in quantity and degradation in quality. This nature of water resources poses immense challenges to management especially in terms of allocation, monitoring, and enforcement.

Inadequate Knowledge Base

Currently, there is the challenge of inadequate baseline information on the existing wetland resources in the country including the bio-physical characteristics, socio-economic and cultural values, as well as the threats that endanger these wetlands. Key baseline data is critical in the evolution of a comprehensive sustainable management protocol for wetlands. There are no comprehensive inventories currently being carried out on wetlands. However, a wetlands inventory framework is being developed with plans to scale it up as a nationwide wetlands inventory.

Coordination challenges

Water is a resource that is of utility to many types to uses and users and stakeholders. This requires water resource to be properly regulated and managed in an integrated manner. The Water Act of Bhutan 2011 requires water resources to be managed in an integrated manner. NEC is the designated apex body with the responsibility for overall coordination of water resource management in the country. The line agencies including Ministries at the national level and local governments i.e., Dzongkhag, Gewog, and Thromde Administrations as competent authorities are required to work in coherent, integrated and coordinated manner. However, coordination has been the single most challenge. Lack of organizational capacity and lack of cooperation from concerned agencies make IWRM implementation practically difficult.

The background of the current staff in Watershed Management Division (WMD) is in forestry with limited professional expertise in watershed management. Interdisciplinary knowledge that is vital in watershed management also needs to be embedded within their professional expertise. These capacity constraints impact their engagement in watershed management activities, especially watershed assessments and in developing intervention measures. There is constant churn of staff leading to many experienced staff leaving the department. Further, there are varying capacities among the technical personnel in forestry field offices who support the WMD in carrying out the watershed management activities. Overall, the lack of professional expertise and the required technical training is a constraint facing the department and its field offices. The inter-related sectoral issues related to watershed management and the ability to identify and intervene with appropriate measures is a huge challenge in the watershed management sector both nationally as well as locally. Capacity needs to be built up in carrying out hydro-geological mapping, identifying recharge areas and designing appropriate measures. The field staff require adequate training and expertise to fully comprehend and implement the watershed related activities in the field. Periodic capacity building initiatives for the staff at WMD are limited. However, at field offices, there are capacity building interventions during the implementation of watershed management activities.

For example, an immediate need is the capacity to address the issue of drying up of springs/water sources that is a country wide problem. There is a lack of capacity to assess its causes and to design appropriate measures, particularly, capacities to carryout hydro-geological mapping, identifying water recharge areas, and designing fitting intervention measures to revive the water sources. Wetlands inventory framework is being currently developed, after which a nationwide wetlands inventory is planned to be prepared. For this exercise, sustained training efforts for field office staff are required. As there are no regular training initiatives for WMD and Field Offices, a capacity building and training plan needs to be introduced to address this issue. There is only a single staff who is directly involved in wetlands management, supported by forestry field offices staff. The DoFPS and MoAF have to rely on other agencies for engineering and technical services. Timely assistance is therefore a challenge and is subject to their availability.

Poor awareness and clear legal framework for wetland management

There is an emerging need to increase awareness to support watershed management approaches and its effective implementation in Bhutan across stakeholders. In general, a concern that was highlighted is that watershed management interventions while needing a multi-sectoral approach, receive less priority when compared to sector specific plan activities. In this context, the interventions in watershed management are seen as duplication of activities. All these are further compounded by the lack of a continued funding support. It is important to note that the 2016 watershed management guidelines underline the need for developing an Integrated Watershed Management Plan that can form the basis for an overall Integrated River Basin Management Framework for each basin. The guidelines have also stressed the importance of an M&E process of watershed classification. A key concern raised by the ministry was a general lack of awareness about the concept of wetland management. It was felt that people fail to appreciate the intrinsic values of wetland resources except for the limited consumptive use of some of the wetland resources. This lack of awareness among community members often generated negative tendencies putting the well-being of wetlands at risk.

Wetland management and its conservation are comparatively a new initiative that the country is trying to address. Bhutan has acknowledged the organic linkage between watershed management and the need for complementary management of wetlands. As mentioned earlier, even the Water Act and Water Regulation only touch upon the presence of wetlands. This concern was also mirrored by the MoAF that currently they did not have a legally binding institutional framework for the management of wetlands and the eco systems around it. Further, different government agencies such as NEC, NCHM, MoWHS and local governments were involved in various aspects of wetland conservation and management, without a clear legal framework. The need was felt for harmonizing the roles and responsibilities of the various agencies responsible for the protection of wetlands. The FNCRR-2017 while highlighting on the creation and implementation of wetland management plans does not elaborate much on critical details of inter-sectoral coordination and other approaches that is essential for wetland management.

Vulnerability to Climate change

Climate change has been observed to impact water availability at the local levels. Climate projections reveal that rainfall is expected to be more intense in the future particularly in the southern parts of the country. Further, expected increase in temperature from global warming is already causing increased melting of snow and glaciers. The impact from the above phenomena makes the country vulnerable to

I) Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOF), ii) Increased run-off and flash floods, iii) Drying up of water sources

GLOFs are a considerable concern in mountainous areas as they can lead to substantial loss of life and damage to property and infrastructure in already vulnerable areas.

Infrastructure and Investment challenges

A key concern raised by the ministry is inadequate funding for scaling-up some of the activities related to watershed and wetland management and conservation.

Owing to spatial and seasonal variations in water availability, Bhutan could scale-up investing in water storage and accessibility. However, due to sparse rural settlements that are settled on the slopes, the per capita investment for installation and maintenance of water storage and supply is relatively expensive compared to urban areas.

In urban areas, water supply services are primarily subsidized, inefficient, with high percentage of non-revenue water. Despite the feasibility of improved water services through privatization or corporatization of water supply services, water supply services in urban areas remain largely ineffective and inefficient.

Social Challenges

Though Bhutan has abundant water resources (70,576 million cubic meters per year), accessing them for drinking and irrigation purposes is not easy due to the country’s difficult terrain. Rapid human population growth in both urban and rural areas is adding more pressure on available water resources due to increases in agricultural farming, industrial and domestic uses.

Owing to change in lifestyles, increasing per capita consumption is imposing immense demand for improved water supply.

Water pollution from urbanization, inefficient solid waste management, industrial effluents, intensive agriculture and use of pesticides and fertilizers are causing water pollution.

Need for an Integrated Approach

There is a need to consider these issues in an integrated, spatial approach with a hydrologic unit like a watershed or aquifer to explore the inter-linkages.

A watershed is any surface area, where sources of water, including rainfall and snow melt, collect and drain to a larger water body. Drop by drop, water is channeled into soils, groundwater, creeks, and streams, making its way to larger rivers and eventually the sea. Everyone in the world lives in a watershed, with boundaries defined only by elevation. The watershed at any point is comprised of the upstream area that drains into that point.

Watersheds can be aggregated at different scales – from a small mountainous micro-watershed (such as in Nepal’s Kosi basin), to a large trans-boundary watershed such as the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna or the Indus. The terms watershed, basin, and catchment are often used interchangeably although in some countries, catchment refers to upstream hilly areas where much of the precipitation in a watershed may occur.

Watersheds form the basic building blocks for land and water planning. Every location on land is part of some watershed. Explore the watersheds around the world by clicking on the map below to outline the upstream land area that drains into that point clicked.

Watersheds are comprised of multiple biophysical and socio-economic elements. Biophysical elements are influenced by climate (rainfall, altitude, solar radiation, winds), drainage, soil, vegetation, topography (slopes, erosion features such as rill, gullies, and landslides) and land use patterns (homesteads, cultivated land, grazing land, forests, degraded areas). Socio-economic elements of a watershed involve population and their economic activities (agriculture, livestock, industry, tourism). Watershed management is multi-sectoral in nature due to the multitude of human activities that coexist within them.

All elements and activities in a watershed are interrelated. Any activity that affects water quality, quantity, or flow rate in one part of the watershed may affect locations downstream. For example, deforestation in upstream reaches could increase soil erosion that could impact the storage of any water storage (e.g., dams) or reduce stream channel capacity through sedimentation that could reduce the availability of water in some cases and increase the hazard of riverine floods in other cases. Understanding this multi-sectoral spatial connectivity within a watershed is essential when planning or managing activities for the future.

Watersheds provide a variety of ecosystem services and economic benefits that can be leveraged through sustainable watershed management. Evidence has shown that managing a watershed sustainably can generate multiple benefits, including socio-economic and ecological gains. Sustainable watershed management maintains critical ecosystem services including improving water quality through filtering pollutants, nutrient cycling, and sediment retention; flood control and increased resilience to the impacts of climate change; habitat provision for biodiversity; carbon sequestration and storage; and the provision of critical goods such as food or timber. Other economic benefits afforded by watersheds include reduced costs for providing drinking water, maintaining infrastructure; flood prevention and damage recovery; and hydropower production. Well managed watersheds can also offer health benefits, such as lower rates of illness where water is cleaner as a result of the filtering service of the watershed.

Investing in the maintenance of healthy watersheds has many economic benefits. Many ecosystem services such as carbon storage, nutrient cycling, water filtration and storage, air filtration, and soil formation are often under-valued when making land use decisions. Assigning monetary value to these ecosystem services is essential for encouraging conservation and its associated economic benefits for the local communities. Maintaining riparian connectivity and natural processes in the landscape ensure sustainable and cost-effective provision of clean water over time. Investing in the maintenance of healthy watersheds can significantly lower costs associated with water treatment and flooding.

These issues are important at different scales – not only for large watersheds upstream of hydropower plants – but also for the micro watersheds associated with the small water sources that are critical for water provision around the country. Recent reports indicate that of the 6,555 water sources assessed in 19 or 20 dzongkhags in Bhutan (Gasa was left out as it was assumed to not have a scarcity issue) by the MoAF under a Strategic Program for Climate Resilience preparatory project, about 35% (2,317) were in the process of drying and 2% (147) had completely dried up. This was particularly the case in Samtse, Wangduephodrang and Trashigang Dzonkhags.

This points to a need for a more integrated water resources management approach supported by an adequate knowledge base for the relevant watersheds around the country that provide critical water supplies specially to explore options to improve reliability of water supply and manage demands given intra-annual, inter-annual, and climate change considerations.

For more information on more integrated watershed/landscape approaches with examples drawn from around the world, please check out these free resources.

Emerging Opportunities

- Technology :

Many smart water infrastructure technologies are paving the way for a better future and have the potential to contribute significantly to improved service delivery and efficiency. Some of them include Smart Metering, District Metered Areas, Pressure Management, Active Leak Detection, Management Information Systems, Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA), Hydraulic Modeling, etc. Mellinger 2017 - Educated youth:

- Mainstreaming of Sustainability…

The IWRM Process

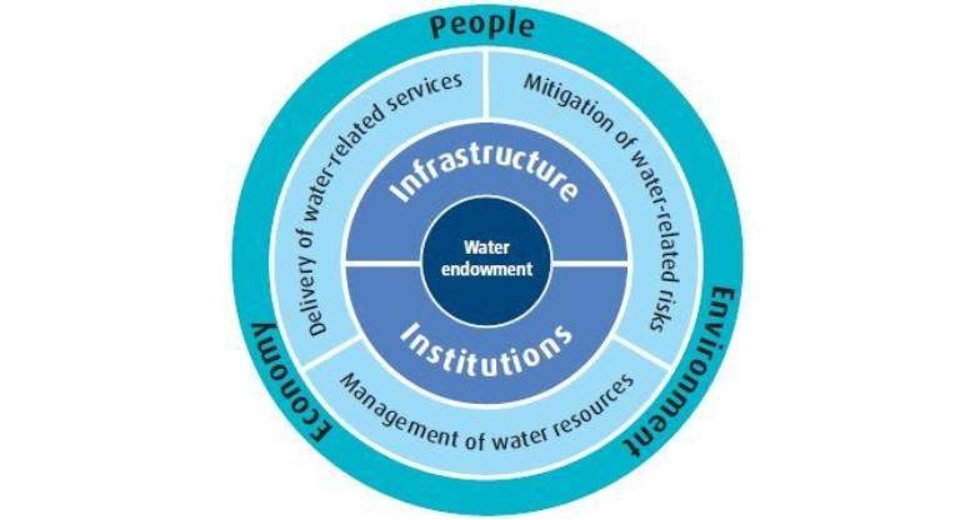

IWRM is a process to promote the coordinated development and management of water, land, and related resources to maximize economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems.

Key components of IWRM are as follows. First, managing water at the basin or watershed level, which includes integrating land and water, upstream and downstream, groundwater, surface water, and coastal resources. Second, optimizing supply , which involves surface and groundwater supplies assessments, water balances analysis, wastewater reuse adoption, and evaluating the environmental impacts of distribution and use options. Third, managing demand, includes adopting appropriate water/scarcity pricing and investment cost recovery policies, utilizing water-efficient technologies, and establishing decentralized water management authorities. Fourth, providing equitable access, includes support for effective water users’ associations, involvement of marginalized groups, and consideration of gender issues. Fifth, establishing policy, examples include implementation of the polluter-pays principle and market-based regulatory mechanisms. Sixth, utilizing an inter-sectoral approach to decision-making, where responsibility or authority for managing water resources is well-coordinated and stakeholders have a share in the process ( Wangchhu Basin Management Plan 2016).

Framework for IWRM in Bhutan

The operational framework for implementation of IWRM is captured in the National IWRM Plan (NIWRMP) of 2016. The plan was prepared based on the legal and institutional framework described in section 2.1 above. The plan was formulated by the National Environment Commission (NEC) with technical support from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and under constant guidance and advice of the technical advisory committee (TAC) comprising of representatives of water related competent authorities and stakeholders. 3 The plan was based on several technical assessments including hydrological and climate modelling, assessment of existing institutional mechanisms, and organizational capacity. Regional and national level consultations and sensitization workshops were held before finalization and adoption of the plan by the NEC. In the process of developing the plan, the NEC was also able to put in place the technical advisory committee, which later became Water Resource Technical Advisory Committee (WRTAC) to the Water Resource Coordination Division (WRCD). The Wangchhu Basin was prioritized as the first basin to be piloted for implementation of IWRM. For this, the Wangchhu Basin Committee (WBC) was established. With technical assistance from the ADB TA (Technical Assistance), the Wangchhu Basin Management Plan was also developed and endorsed by the WBC.

The operational framework for IWRM as contained in the NIWRMP 2016 further elaborates on the principles, approaches, and mechanisms specified in the Water Act. To facilitate coherent and integrated planning, implementation, monitoring, and reporting progress towards water security, the plan demonstrates the following processes and concepts:

1. Identification of common goal and priority interventions

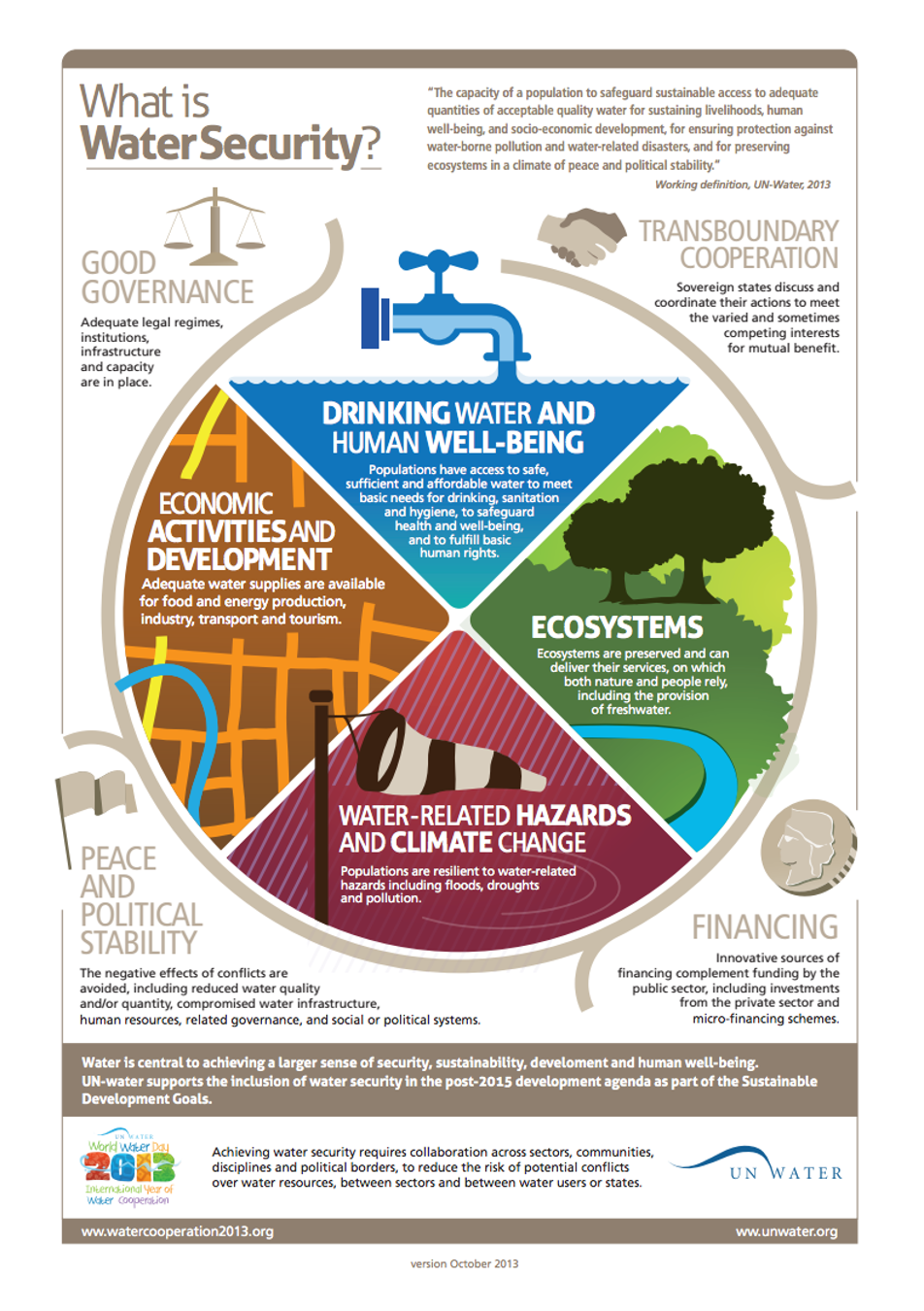

The first step to getting all agencies and stakeholders to cooperate and work together is to define a common purpose for which they must work together – sustainable water resource management in the country. Based on a comprehensive assessment of the situation of water and water resource management in the country, the plan identifies priority issues and challenges to be addressed. In formulating the interventions to address the issues, the NIWRMP 2016 defines water security as the overall national goal of water resource management.

Water Security is defined as “ the capacity of a population to safeguard sustainable access to adequate quantities of acceptable quality water for sustaining livelihoods, human well-being, and socio-economic development, for ensuring protection against water-borne pollution and water- related disasters, and for preserving ecosystems in a climate of peace and political stability ” (UN Water).

2. Bhutan Water Security Index

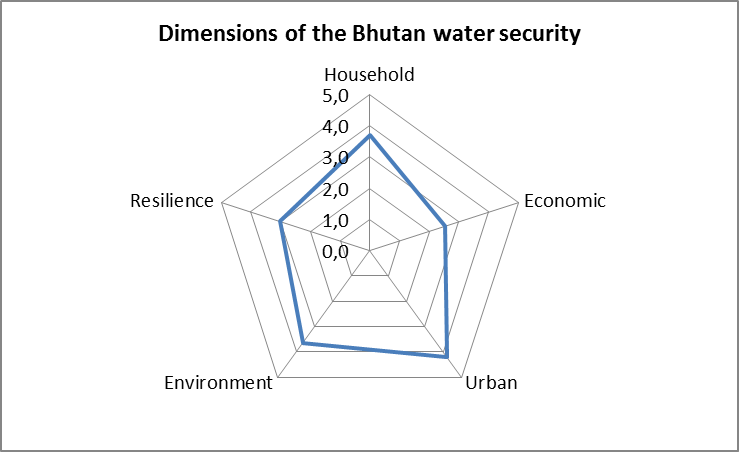

Having defined ‘Water Security’ as the overall goal of IWRM, the NIWRMP introduces the concept of Bhutan Water Security Index (BWSI) comprised of five dimensions, 11 sub-dimensions, and 57 indicators. This concept categorizes the areas of water resource management into five dimensions, which are essentially objectives of IWRM to be pursued by concerned sectors. The key dimensions of water security are:

i.Rural Water Security – to satisfy household water and sanitation needs in all communities.

ii.Economic Water Security – to Support productive economies in agriculture, industry, and energy.

iii.Urban Water Security - Develop vibrant, livable cities and towns.

iv.Environmental Water Security - Restore healthy rivers and ecosystems; and

v.Disaster and climate resilience - Build resilient communities that can adapt to change.

Table: Water Security key dimensions, sub-Key dimensions, and Indicators

| Key Dimensions | Sub-key dimensions | Indicators |

| 1. Rural Water Security | - | 3 |

| 2. Economic Water Security | 4 | 12 |

| 3. Urban Water Security | - | 5 |

| 4. Environmental Water Security | 4 | 12 |

| 5. Disaster and climate resilience | 3 | 25 |

| Total | 11 | 57 |

Source: Revised Bhutan Water Security Index: Dimensions, Indicators and Calculations NECS. April 2018

3. Institutional arrangements and coordination framework

Actors in an action arena are more likely to cooperate and work in coherence with each other if the actors have and are aware not just of their own mandates and roles but also able to relate to the role of other players. The players in IWRM implementation may be described in terms of the following roles:

Water allocator, coordinator, and regulator

National Environment Commission is the apex body for all matters related to the environment as per NEPA (National Environmental Protection Agency) 2007. Further, the Water Act of Bhutan 2011 as per Article 13 b) explicitly states that NEC shall ‘ Co-ordinate national integrated water resources management.’ Unless otherwise exempted under Article 33, an environmental clearance from the NEC or the concerned Competent Authority is the pre-requisite to abstraction of water by any person or entity. This implies that abstraction of water, unless exempted under Article 33, must be allocated in the form of environmental clearance. Based on this, the NEC is the national level agency for allocation of water for purposes requiring.

The Competent Authorities, as per Article 15 of the Water Act may be categorized into following roles:

Water resource protection and ecosystem service provider

Water resources of Bhutan originate primarily from the glaciers, snow reserves, and forest areas comprising of watersheds, wetlands and water bodies that need to be protected and conserved. As the custodian of the Forest and Nature Conservation Act 1995 and as per Article 45 and 46 of the Water Act, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forests and its Department of Forest and Park Services (DOFPS) is the primary player when it comes to protection and management of water resources in forests and wetlands in the country. Accordingly, the DOFPS plays a particularly important role in the sustained provision of forest products and ecosystem services. All programmes and activities of the DOFPS executed through the Watershed Management Division (WMD), Forest Resource Management Division (FRMD), the Forest Protection and Enforcement Division (FPED), Social Forestry Division (SFD) and Nature Conservation Division (NCD), have direct and indirect contribution to protection and management of watersheds that enable sustained availability of water in the streams, rivers, and lakes. The programmes and activities are implemented at the local level through the network of divisional forest offices and protected areas management.

Water resource information provider

The National Centre for Hydrology and Meteorology (NCHM) plays a particularly key role as the official source of information on water resources that is crucial for institutions like the NEC and river basin committees (RBCs) to determine the amount of water in the basins and to make water allocation decisions for different purposes. Through its network of hydrological and meteorological stations across the country, NCHM (National Center for Hydrology and Meteorology) collects and maintains raw data as well as carries out hydrological and climate modeling and analysis. Further, the NEC has also delegated NCHM with the responsibility to collect and provide information on ambient water quality.

The Royal Centre for Disease Control (RCDC) is the provider of information on drinking water quality in the country.

The field divisions with the support from WMD carry out watershed assessments and the record are compiled centrally by the WMD. These assessments identify issues and are used to classify watersheds as pristine, normal, degraded, or critical. Watersheds that are classified as degraded or critical are further assessed in-depth for corrective interventions.

The first round of assessments is currently on-going. The information regarding the watersheds is used by the field offices and local governments for providing clearances for developmental work and other interventions in the watershed areas.

Watershed classification guidelines were brought out by the WMD in April 2016. This was necessitated in the context of increasing watersheds being degraded due to increase in population, land use changes and development of infrastructure.

Water supply service provider

The MoWHS is the mandated service provider for urban water supply and sanitation. The Department of Engineering Service (DES) and its Water and Sanitation Division (WSD) in particular are responsible for planning and implementing water supply infrastructure and services towards the objective of providing equitable access to adequate drinking water supply to urban areas. Under an MOU (Memorandums of Understanding) between MOWHS and MOH (Ministry of Health), the mandate for rural drinking water supply services is also transferred to MOWHS.

For irrigation services, the Irrigation Division of the Department of Agriculture, MOAF (Ministry of Agriculture and Forests) remains the implementing agency. The local governments i.e., Thromde and Dzongkhag administrations are the water supply service providers at the basin level. While Class A Thromde Administrations are responsible for water supply and sanitation services in urban areas, the District engineering sections under Dzongkhag Administrations are responsible for providing water supply services in both Dzongkhag municipalities as well as Gewogs in the district.

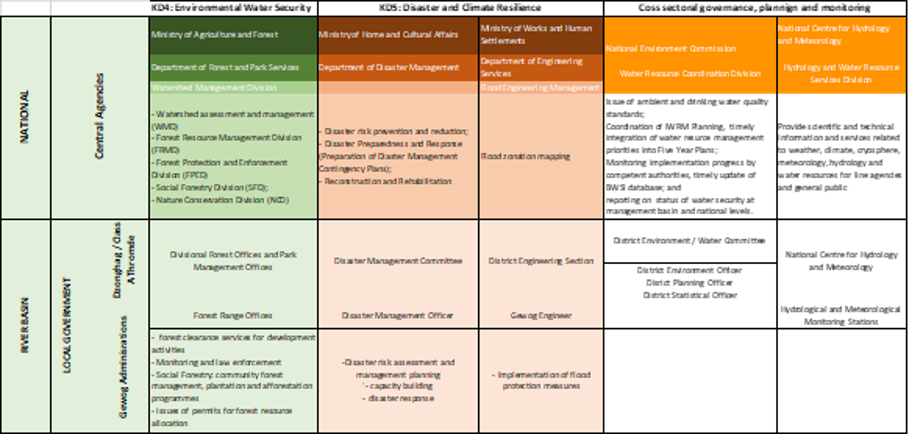

The inter-agency coordination framework identifies the mandate and role of water agencies and stakeholders against the BWSI key dimensions. This framework provides competent authorities at the national and river basin levels with an understanding about their respective roles in fostering water security while being able to relate to and appreciate the role of other agencies in achieving the overall goal of water security. A comprehensive overview of the interagency coordination framework for IWRM is given in the table below.

Table: Institutional arrangements depicting agency mandates against key dimensions of water security.

An important aspect of institutional arrangements for water resource management is the segregation of agencies roles by regulatory and implementing mandates. For clarity of agency roles in IWRM, the NEC and its Secretariat NECS are the coordination and regulatory agency at the national level while the river basin committee (RBC) and its Secretariat are the coordinating agency at the river basin level. The competent authorities are implementing agencies at national and basin levels that plan, implement and report on progress towards their sectoral water security objectives.

Another aspect of clarity of roles relates to resource allocation roles against resource user roles. The NEC and its Secretariat is the national agency for water allocation, which is carried out through the process of environmental clearance of projects. The district environment committee, which also serves as the water committee, with support from the district environmental officer serves as the water allocation agency at the river basin level. However, since this role is attached to the environmental clearance process, the extent of the power to allocate water resources is guided by the NEC’s guidelines for environmental clearance of projects.

Institutional arrangements: Agency mandates for key dimensions of water security

Wetland Management

The FNCRR 2017 provides detailed responsibilities of DoFPS regarding the conservation of wetlands. It is responsible for planning, coordination and implementation of wetland management plans, and protection of wetlands as per technical guidelines provided in the Forest Management code of the DoFPS. Wetland management too requires sustained, concerted, coordinated inter-sectoral engagement. The National Environment Commission (NEC), Ministry of Works and Human Settlement (MoWHS), Department of Agriculture (DoA), National Center for Hydrology and Meteorology (NCHM), Dzongkhag administrations, local governments and field offices are some of the key stakeholders involved in wetland management. Policies for wetland management in Bhutan are formulated by the Watershed Management Division (WMD) on behalf of the DoFPS and under the guidance of MoAF. The asset management, infrastructure development and maintenance are the responsibilities of the respective field offices along with the WMD. The respective field offices, that is, the Protected Area Offices or Territorial Divisions is responsible for the provision of service. The WMD and the DoFPS are responsible for providing technical support and supervision. The financing of the service is done through the central government and the donors. The financial and administrative regulation is the responsibility of the DoFPS.

Apart from other wetlands, Bhutan has three sites designated as wetlands of international importance (Ramsar sites) with a surface area of 1225 hectares. While there is data available pertaining to these Ramsar sites, a national database of wetlands in the country is yet to be developed. Currently the WMD is producing the framework for national wetland inventory, after which a national wetland inventory will be carried out and a database on wetlands will be instituted.

The local governments discuss issues related to wetland conservation, review the progress of implementation and plan interventions, and facilitate in conflict management. They are also responsible for the integration of the planned activities into their annual plans and to explore funding for the implementation of these activities. They also assist in the protection of the riparian zones and streams. In all these activities, the forestry field offices take the lead role, while the local governments collaborate and provide necessary support. Where activities in the wetland were outside the mandate of the DoFPS, for instance, like those related to agriculture or livestock, the local governments take the lead and forestry field offices collaborate and provide required support.

The preparation of the wetland management plans is led by the WMD; however, this activity is now being gradually transferred to the forestry field offices. The mandate for implementation in the wetland management sector is with the field offices under the department and the local government. The monitoring is jointly done by the WMD and the local government. The last mile hand holding on wetland management plans for the local community and users is provided by the field office under the DoFPS with the technical guidance from WMD.

Participation and Monitoring

Community participation in wetland management is driven by awareness programs, consultation meetings, discussions, field visits and surveys. The objective is to ensure that representatives from all households from the wetlands site irrespective of their status and group participate. In order to guarantee their ownership for prioritization and successful implementation of the plan, the community is involved from the assessment stage until the completion of plan. The performance of the implementing agencies is monitored periodically against those activities outlined in the work plan. The monitoring of the performance is done by Watershed Management Division in consultation with the watershed communities and implementing agencies. There is an annual monitoring that is carried out by the field offices while the evaluation of the impact of interventions in wetland management is carried out by the WMD. The results collected through monitoring programs are expected to be in parallel with the targets of the management plan and corrective measures are applied if ongoing work plan and planned activities does not meet the expected targets adequately. However, currently there is no specific framework for performance monitoring or service charters in place. With regard to grievance redressal, efforts are made to resolve any issue through discussions within the DoFPS and if it remains unresolved at this level, recourse is taken according to the law of the land.

4. Delineation of management basins

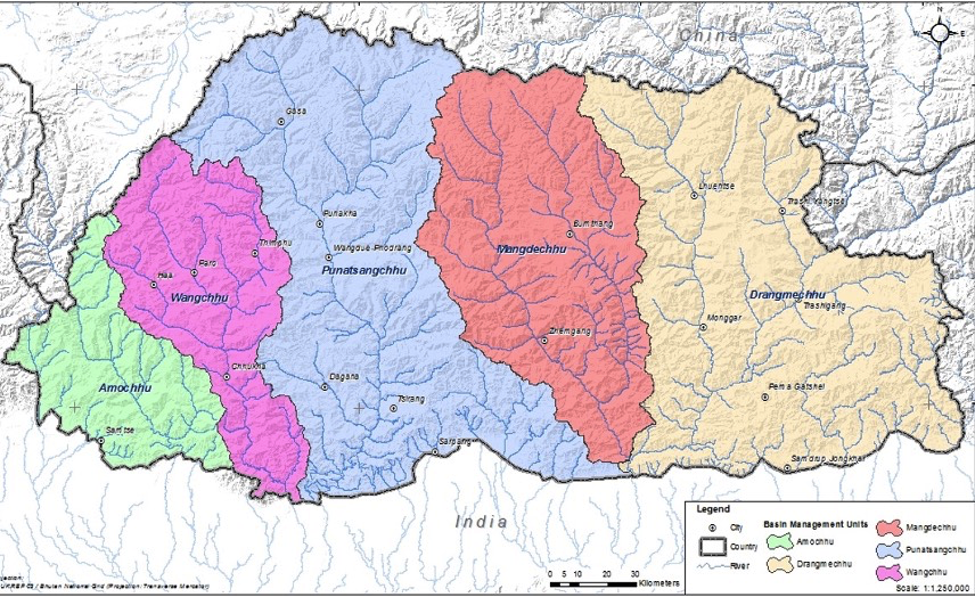

Bhutan has five major and several smaller hydrological basins. While it is theoretically appropriate to pursue water resource management interventions at the level of hydrological basins, the NIWRMP identified the difficulty of putting in place river basin management committees for each hydrological basin – the Manas basin, which covers around 50% of the country, is too big for an RBC to manage while the smaller ones are too small and not administratively feasible or cost effective. To address this issue, the NIWRMP introduced the concept of Management basin as the unit of river basin management. The management basins are based on integration of hydrological and administrative boundaries with smaller hydrological basins integrated into larger ones. The Management basins are i) Amochu, ii) Wangchhu, iii) Puna-tsangchhu, iv) Mangdechhu and v) Drangmechhu. The Bhutan map depicting the Management basins are shown in the figure below.

Figure: Delineation of River Basins for IWRM Planning and Management

Source: NIWRMP 2016, NEC

5. Framework for planning, monitoring, and reporting.

The BWSI is the primary basis for planning, implementation, monitoring, and reporting progress towards the goal of water security at basin and national levels. The proposed modality for planning, implementation, monitoring, and reporting are described below:

Integration of IWRM priorities into five-year plans : No plans are likely to be provided with the required funds if they are not part of the priorities identified in the five-year plan. For this, the NECS as the coordinating agency, has the responsibility of ensuring that water security is identified as a National Key Result Area in the upcoming FYP (Five Year Plan) and the timely integration of the priorities of the competent authorities in meeting their sectoral water security objectives.

The priorities of the competent authorities should be identified along the key dimensions, sub-key dimensions, and the parameters identified against the competent. The concerned competent authority, based on the relevant issues and priorities, is expected to formulate the Agency KRA (Key Result Areas) and key performance indicators (KPIs). Likewise, the local governments are expected to formulate the local government KRA (LGKRA) and KPIs.

Monitoring progress towards water security: During the period of implementation of the FYP, the NECS as the coordinating agency for WRM (Water Resources Management) shall liaise with the competent authorities on the implementation progress. For this, the competent authorities are expected to designate a focal person with the responsibility to collect, compile and enter the Bhutan Water Security Index System (BWSIS) the data/ information on the progress indicators and parameters related to each basin. Logically, the data inputs are required at the district level such that information on water security at the district level should result in water security information at management basin level, which cumulatively results in the status of water security at the national level.

Visualization of water security status: Progress towards water security is measured on a scale of 1 to 5, which can be computed using the guidelines for computation of scores for each of the water security dimensions based on the data collected for the indicators and parameters. The results when projected in a scale of 5 is represented on a five-dimensional spider diagram (see figure below), which allows decisions makers to ascertain progress from last reporting as well as use it to define targets for the next implementation phase.

5. Framework for planning, monitoring, and reporting.

The BWSI is the primary basis for planning, implementation, monitoring, and reporting progress towards the goal of water security at basin and national levels. The proposed modality for planning, implementation, monitoring, and reporting are described below:

Integration of IWRM priorities into five-year plans : No plans are likely to be provided with the required funds if they are not part of the priorities identified in the five-year plan. For this, the NECS as the coordinating agency, has the responsibility of ensuring that water security is identified as a National Key Result Area in the upcoming FYP (Five Year Plan) and the timely integration of the priorities of the competent authorities in meeting their sectoral water security objectives.

The priorities of the competent authorities should be identified along the key dimensions, sub-key dimensions, and the parameters identified against the competent. The concerned competent authority, based on the relevant issues and priorities, is expected to formulate the Agency KRA (Key Result Areas) and key performance indicators (KPIs). Likewise, the local governments are expected to formulate the local government KRA (LGKRA) and KPIs.

Monitoring progress towards water security: During the period of implementation of the FYP, the NECS as the coordinating agency for WRM (Water Resources Management) shall liaise with the competent authorities on the implementation progress. For this, the competent authorities are expected to designate a focal person with the responsibility to collect, compile and enter the Bhutan Water Security Index System (BWSIS) the data/ information on the progress indicators and parameters related to each basin. Logically, the data inputs are required at the district level such that information on water security at the district level should result in water security information at management basin level, which cumulatively results in the status of water security at the national level.

Visualization of water security status: Progress towards water security is measured on a scale of 1 to 5, which can be computed using the guidelines for computation of scores for each of the water security dimensions based on the data collected for the indicators and parameters. The results when projected in a scale of 5 is represented on a five-dimensional spider diagram (see figure below), which allows decisions makers to ascertain progress from last reporting as well as use it to define targets for the next implementation phase.

Figure: Water Security visualization diagram – an example

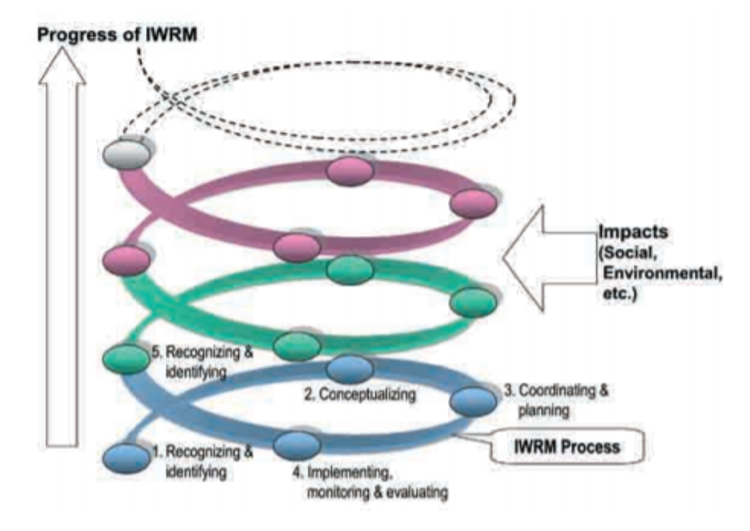

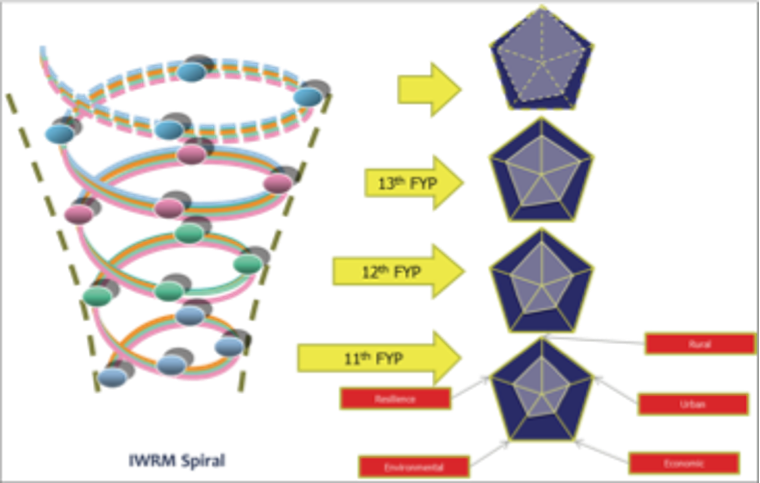

IWRM spiral: Water security is a long-term goal and not something that is achievable in a five-year plan period. Further, there is no straight forward formula to achieve it under changing social, political, economic, and environmental circumstances. Hence, it is more an iterative process of conceptualizing, planning, implementing, monitoring, and evaluating the outputs and outcomes of interventions. The priorities and issues that could not be accommodated or addressed in the previous cycle are incrementally incorporated in the subsequent cycles. This iterative process of learning by doing for IWRM is referred to as the IWRM spiral. As demonstrated in the figure below, the shape and size of the spider diagram represents the level of water security in the basin or country and can be tracked over time to reflect on the progress made in each of the five dimensions of water security.

Figure: Application of IWRM spiral to tracking progress towards water security across five-year plans

The National Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) Plan 2016 focuses on coordination as a center administration rule and specifically expands on a strong Bhutanese custom of water sharing and coordinated management. IWRM serves as the guideline document in the planning and implementation of climate change adaptation to achieve sustainable water security. It provides a comprehensive approach in water management at the basin level incorporating both water and land resources.