Water Resources Context

Bhutan Water Resources and Demands at-a-glance

Water resources in Bhutan include rivers, glaciers, and wetlands, groundwater, and reservoirs

Long-term average annual precipitation in depth: 2,200 (mm/year) (2017)

Renewable water resources: 96,582 m3 per capita (2017)

Water withdrawal: 449 m3 per capita (2008)

Environmental flow requirements: 69 % of the renewable water resources (2017)

Source:SDG6data.org

River Basins

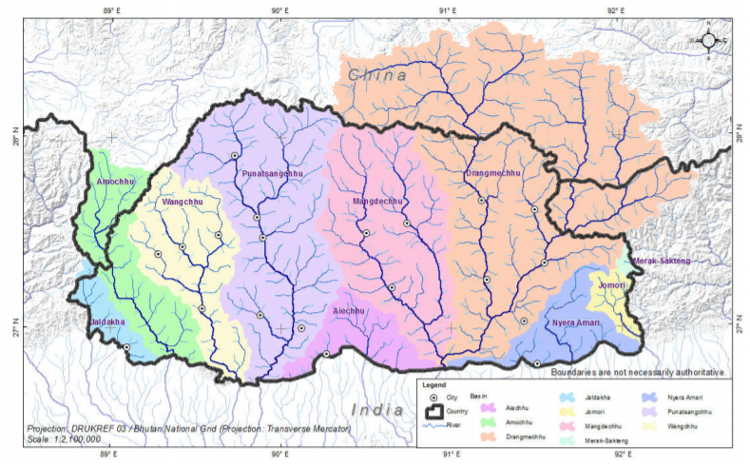

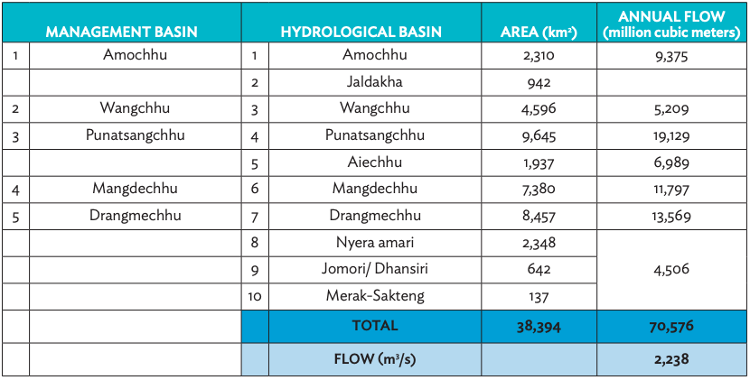

Hydrobasins Bhutan ( ADB, 2016)

According to Water Act provisions, the National IWRM plan promulgates the river basin as the unit of management. Although Bhutan has five major and five minor hydrological basins, it delineates five management basins by integrating the minor basins into the larger ones, this for cost-efficiency and ease of administration of the river basins. All rivers in Bhutan eventually flow to the Brahmaputra River in India (Assam) and it flows to enter the Bay of Bengal through Bangladesh. The total drainage basin of the river is at an area of 580,000 km2 , out of which 50% lies in China, 34% in India, 8% in Bangladesh, and 8% in Bhutan

Source: (ADB 2016)

Manas River is the largest and most extensive river in Bhutan. Its source is from the Arunachal Pradesh district of India and enters eastern Bhutan in the district of Trashigang. It is 376 km long. Manas river consists of three large branches: Mangdechhu, Bumthangchhu, and Drangmechhu. The river serves for irrigation, drinking, economic growth, tourism, and other purposes in the eastern region of Bhutan.

The Wangchhu River runs through the capital city of Thimphu, where most of the country’s population lives. The river originates from the Himalayan glaciers in the country. It is 370 km long river and provides for various purposes like irrigation, drinking, and tourism.

The Punatsangchhu River has two main branches; Phochhu and Mochhu, which meet at Punakha district, and then the river is known as Punatsangchhu. Its source is the great Himalayan range of the country, and it runs for 320 km to join the Brahmaputra River in India. Currently, a hydropower plant to produce 1020 MW of power is being built on the Punatsangchhu River to boost Bhutan’s GDP.

The Amochhu River runs from China to India through Bhutan. The river is 358 km long, out of which 145 km of the river runs in Bhutan. It runs through the southwestern parts of Bhutan. The river adds beauty to the natural landscape of the area and is a major tourist attraction.

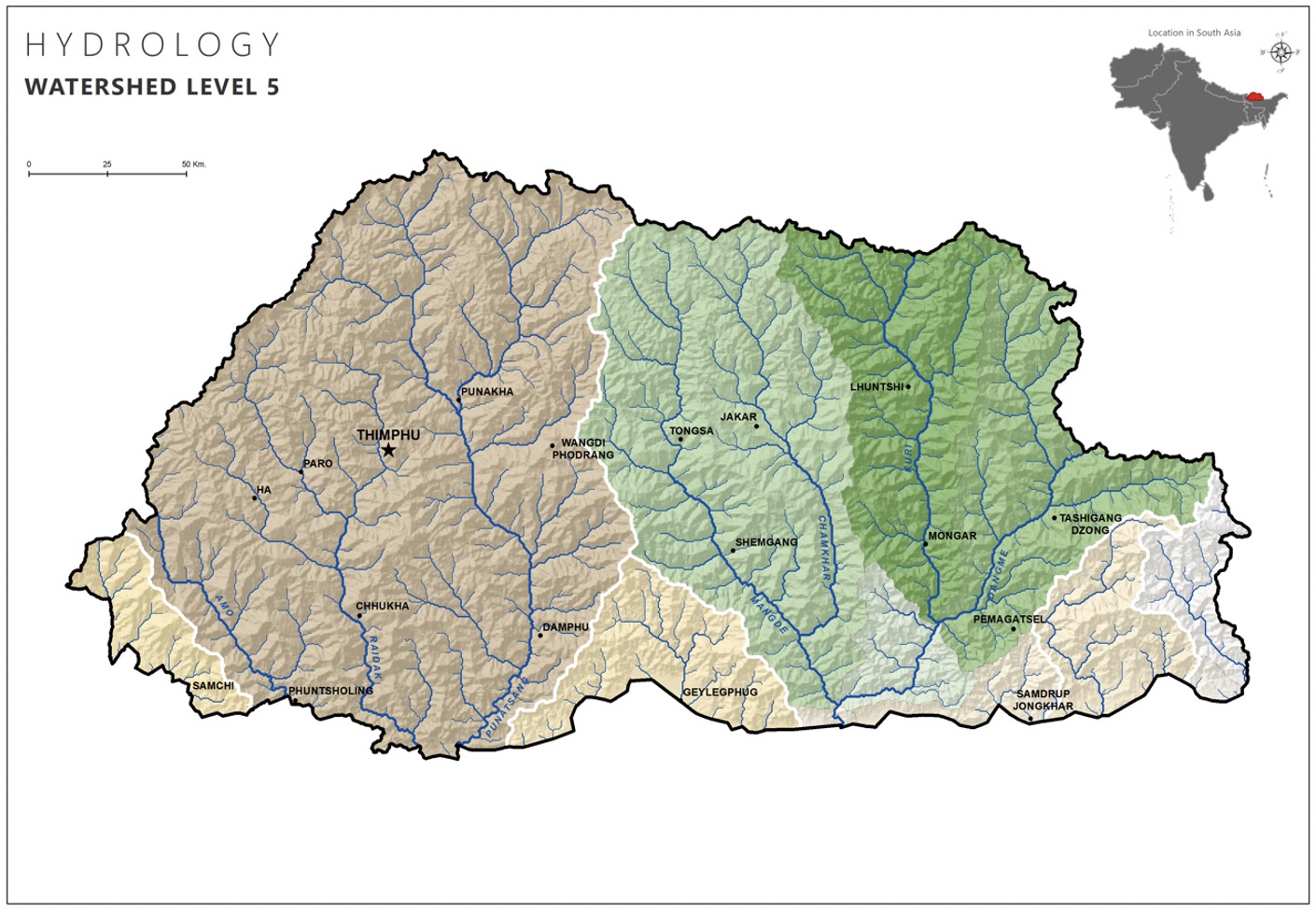

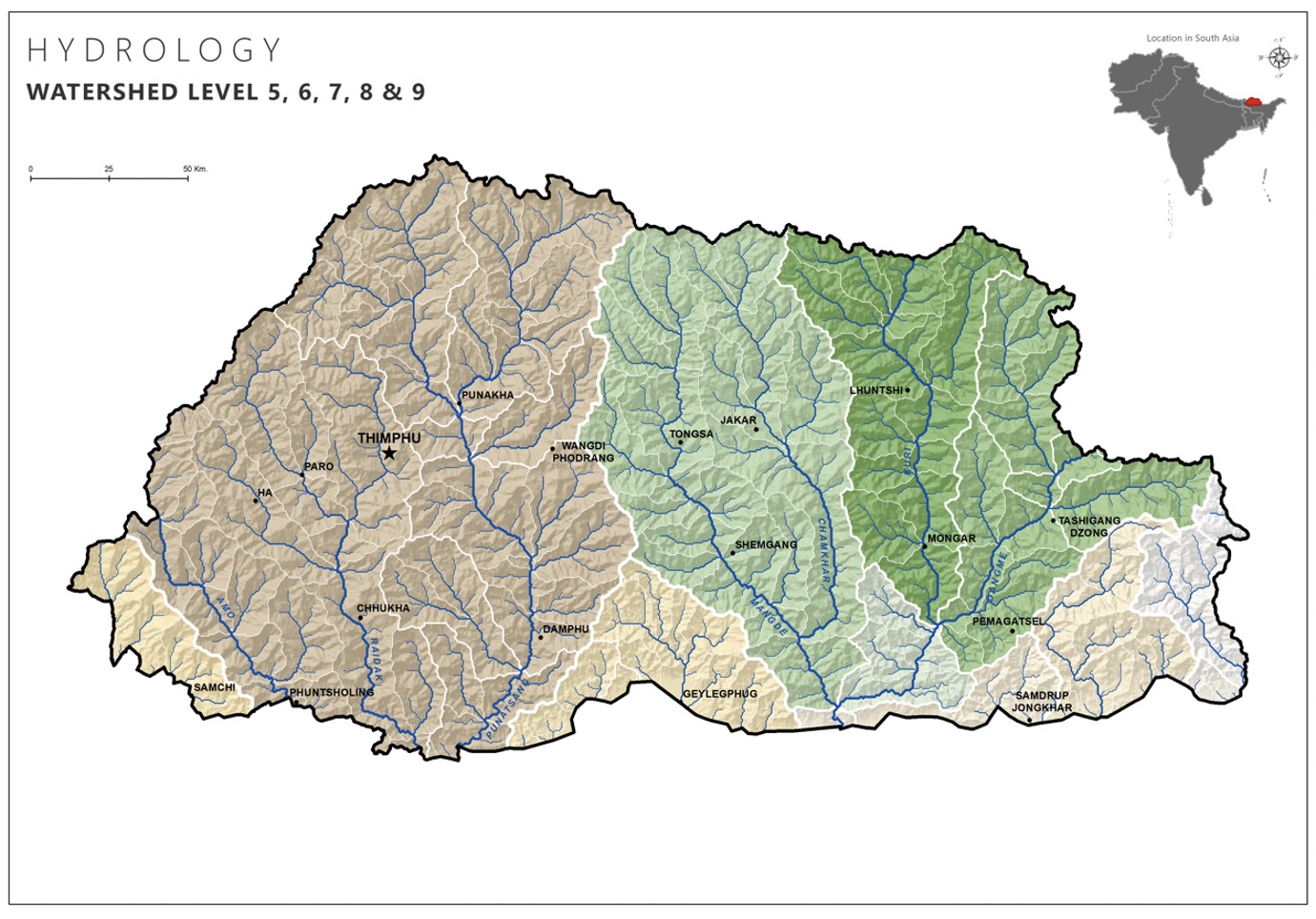

These basins (sometimes also referred to as watersheds or catchments) are composed of smaller hydrologic units at different scales all the way from sub-basins to micro-watersheds.

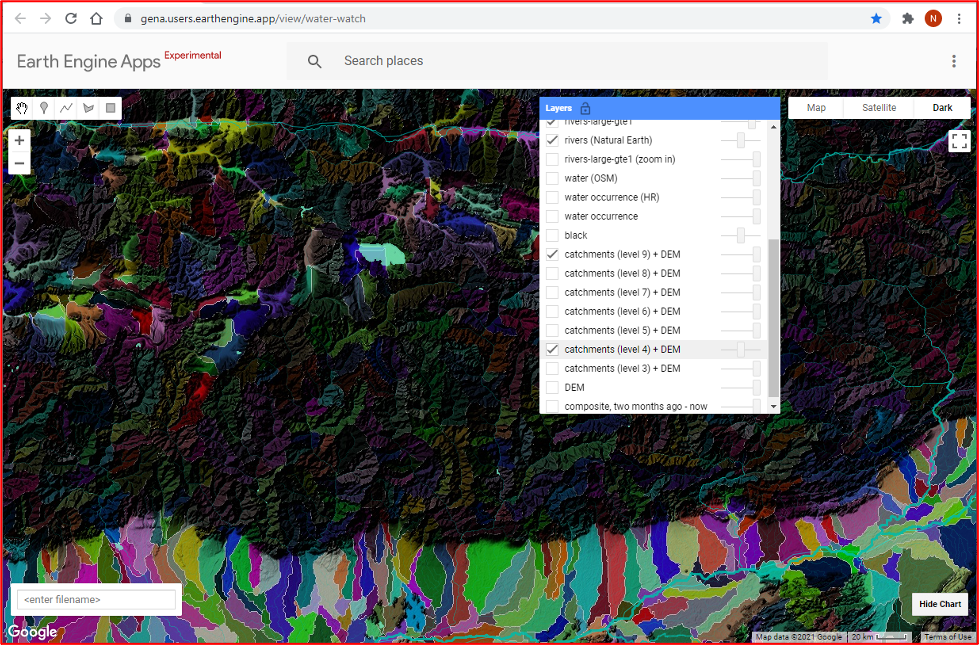

For example, the basins in Bhutan at a more aggregated level (e.g. Hydrosheds level 5) could look like this image below.

And a version at a finer level of disaggregation (Hydrosheds level 9) would look like this map below.

These can be explored interactively at this online interactive application .

Water Supply

Water resources in Bhutan can be best described in terms of i) glaciers, ii) glacial and high-altitude wetlands, iii) rivers and river basins, and iv) groundwater and reservoirs. Combined with snow, ice, freshwater lakes, running streams, rivers, and ground water, Bhutan has one of the highest per capita availability of water in the world. With an average flow of 2,238 m3 /s, Bhutan generates 70,572 million cubic meters per annum, i.e., 94,500 m3 per person per year. (ADB 2016).

Online water supply map of BhutanWater Act of Bhutan 2011 mandates the National Environment Commission (NEC) to a form River Basin Committee (RBC) to manage and develop water resources in the country.

Surface Water

Rivers are primary source of water resource in Bhutan. Most of the country’s rivers originate in the frigid alpine regions of the north, including two in the Tibet Autonomous Region and one in India. Bhutan’s rivers are fed by melting glaciers, snow, and rain. Bhutan has five major and five minor river systems that drain through separate basins. The major river systems Amochhu, Wangchhu, Punatsangchhu, Mangdechhu and Drangmechhu (ADB 2016).

GEOGloWS ECMWF Streamflow Hydroviewer

Groundwater

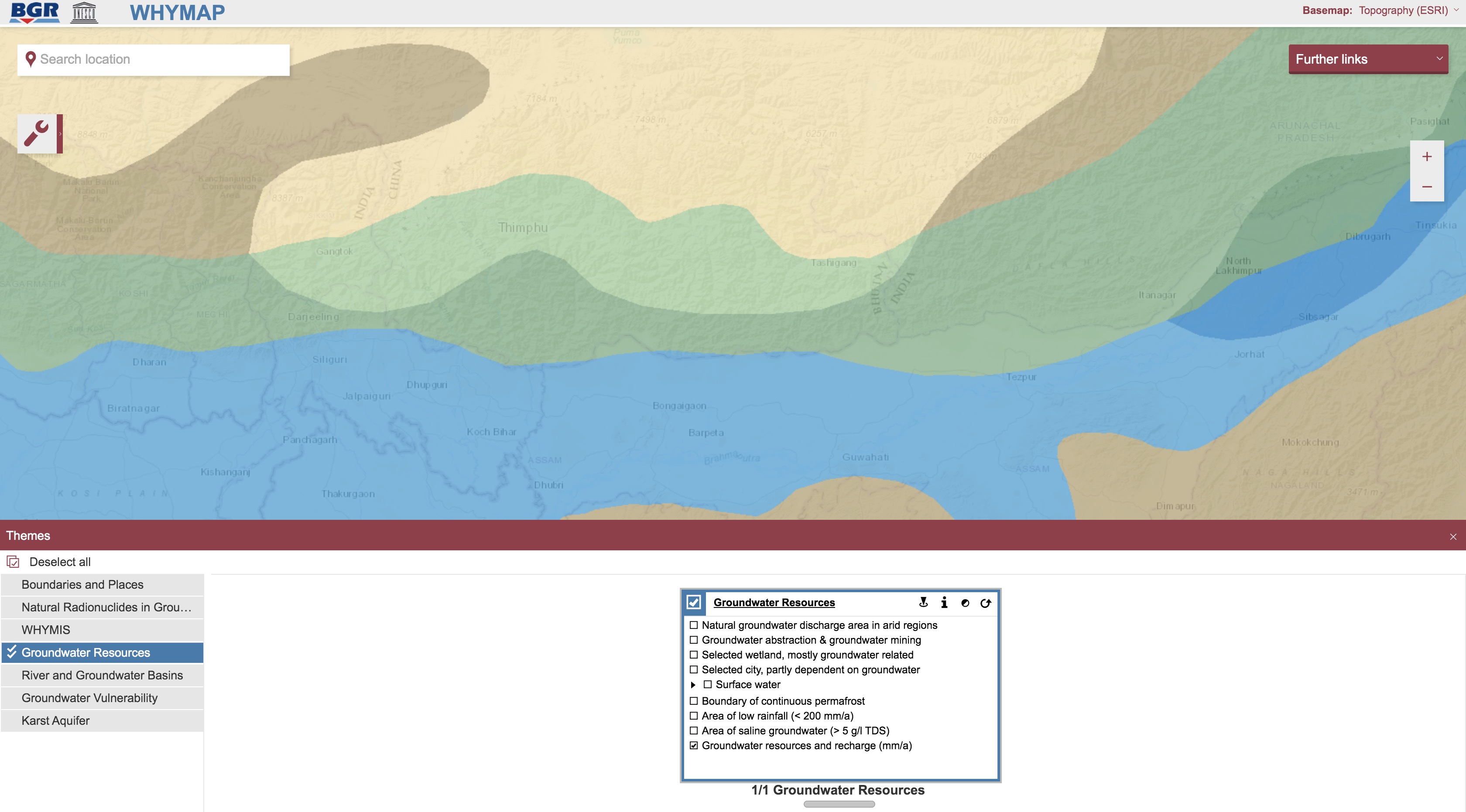

Bhutan’s topography and geomorphic features limit the existence of groundwater and aquifers excepts to the region closer to the Indian border. There are. three major geomorphic features that are the higher Himalayas, the lesser Himalayas and southern foothills that is comprised of fractured crystalline rock. Fractured rock has extremely limited storage capacity and water can only be conveyed along planar breaks. The location of the geomorphic features and recharge rate are displayed in the WhyMap mapping tool below:

The overlap of surface and groundwater, causes a depletion of groundwater resources, as the rivers flow due to it being rainfed. This also causes extreme variations with seasons. there is marginal groundwater extraction in some of the wider valleys in some of the districts of Bhutan, such as Thimphu, Paro, Phuntsholing, Punkaha and Samtse, where there some reserves, but these are only at household levels ( Tariq,Wangchhuk,Muttil, 2021 )

Water Demands

Out of total generated freshwater, it consumes only 1% and drains 99% of water to India. 86% (667 hm3/yr.) of water in Bhutan is used for agriculture, while the remaining 4.5% (36 hm3/yr.) used for domestic and 9.5% (74 hm3/yr.) for industrial purposes.

Agriculture

Bhutan’s economy is dependent on the agriculture, livestock, and forest sectors. It is the source of income for almost 70% of the country’s population who are directly or indirectly dependent on subsistence agriculture. Agricultural products such as potatoes, cardamom, oranges, and apples are exported to neighboring countries like India and Bangladesh. The agricultural sector contributes 15% of total GDP.

Agricultural land has been declining from the strain of population growth, economic expansion, and urbanization. Currently, there is a building ban on irrigated paddy land, so landowners are trying to circumvent the ban by growing highly profitable cash crops on drylands instead of rice paddies. For example, paddy land was reduced by 23 percent from 2006 to 2013, while maize was reduced by 25 percent from 2005-2013. The overall impact of the reduction in arable will reduce crop water requirements, but it will jeopardize food security.

Domestic

36% of the local population use safely managed drinking water. Sub-surface sources, in the form of springs and aquifers, provide water for domestic water supply and small-scale irrigation. An increase in the per capita use of water has raised the sanitation standard and improved the general health of people.

Industrial

Small-scale industries such as mining, cement industry, fishery, beverage industry, dairy farming, ferroalloys, poultry, hot stone bathhouse, and handicrafts all are related to abundant availability of water to the country and contribute to the economy of the country. All these small-scale industries use water directly or indirectly for their production. ( Tariq,Wangchhuk,Muttil, 2021 )

An interactive line chart on Water Withdrawal by Sector:

Water Infrastructure

Dams & Hydropower

With its steep terrain and fast flowing rivers, hydropower is the major backbone of Bhutan’s economy since the 2000s, it accounts for 27% of Bhutan’s revenue and 14% of its GDP. Eighty percent of Bhutan’s surplus energy is exported to India. However, due to low flows in the winter, Bhutan in 2017 imported four percent of domestic electricity from India. There are. seven large operational hydropower plants and 22 mini and micro hydels in Bhutan as of 2020 with a generation capacity of 2326 MW as of 2021 and two more hydropower projects are under construction. Bhutan has the potential to generate 30,000 MW. Hydropower reliance for development and growth makes the country highly vulnerable to climate change impacts that can impact power generation and existing assets.

Irrigation will have a significant impact on hydropower production in Bhutan. Hydropower production occurs in the main rivers and tributaries, while irrigated agriculture occurs in the highlands. Irrigation canals are fed from waterways. Irrigated water demand consumes a significant amount of water via evapotranspiration, which will not be available for hydropower production.

Global Dam Watch:

Irrigation

Drought and inadequate irrigation facilities are major factors affecting low yield in agriculture.

Bhutan’s rivers have steep gradients and narrow steep-sided valleys; thus, they are hardly used for irrigation. The surface water sources used for irrigation are the second and third order tributaries of the main rivers. This means that water for irrigation is not in abundance, as only what flows through the small rivers and streams in the headwater of the water sheds are available.

Water supply

Urban areas have treated water, but municipalities are facing going demand for water quantity and quality due to rural migration. Lower and middle-class residents in cities face constrained water supplies and have to rely on untreated water sources. Delivering a continuous and reliable water supply is challenging since the distribution infrastructure is insufficient and inefficient. Rural water supply obtains water from streams and spring along the slope and do not have proper water source protection or treated water supply.

The distribution of water even in the capital Thimphu has grown organically and needs significant upgrading

Wastewater Treatment

Only 20% of the urban population in Bhutan have access to sewerage treatment facilities. ( source )

The common type of sewage treatment in urban Bhutan are septic tanks that discharge into the environment with minimum treatment or containment.

At present, wastewater treatment plants in Bhutan are overwhelmed due to the rising population with most homes relying on individual septic tanks. Houses are not connected to a treatment plant properly and hence they pollute the water sources and the land. Investing in more treatment plants to meet the current requirements and help reduce the risk of water pollution is the way forward. ( Tariq,Wangchhuk,Muttil, 2021 ).

Policy Context

Prior to 2011, water resources were managed at the de-jure and de-facto levels. At the de-jure level, water resources were regulated under sectoral legislation, regulations, and guidelines. For example, the Land Act of 1979 and 2007 and the Forest and Nature Conservation Act of 1995 and their regulations have provisions on water. In addition, provision of water for drinking and irrigation were based on sectoral policies and guidelines. Drinking water for communities were provisioned through Rural Water Supply Scheme (RWSS) under Ministry of Health while water for irrigation were provided under irrigation policy implemented by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forests. Similarly, the Land Act of 1979, the Land Act of 2007 and the Forest and Nature Conservation Act (FNCA) of 1995 and regulations have specific provisions on water related to their respective mandates. At the de-facto community level, water resources appropriation and management were governed by traditions and customary practices that vary across isolated communities. With the formulation of water policy and subsequent water act and its regulations, the legal framework for water resource management began to take shape. Over time, de-jure water resource management is increasingly being pursued while traditional de-facto water management practices are on the decline.

1. The Water Act 2011 and the Water Regulations 2014

The Water Act of Bhutan 2011 is the first Act that requires the country’s water resources to be managed in a coordinated, coherent, and integrated manner. The rationale for this approach is based on the importance of water as one of the most important resources of the country and the rights of the state over mineral resources, rivers, lakes, and forests as enshrined in the constitution. The Act lays out the principles of water resource management, defines the powers and functions of government and non-governmental agencies, and specifies mechanisms and instruments to be employed for sustainable water resource management in the country. The Water Regulations of 2014 further elaborates on the provisions of the Act.

The Water Act of Bhutan 2011 is the overarching law governing the water sector. The Act declares the country’s water resources as state property and provides the legal basis for IWRM as the primary approach to sustainable management of the resource. The preamble to the Act establishes the point that water resources are not a subject of utility for any one individual or sector but an essential yet vulnerable resource that needs to be managed in a coherent and integrated manner with river basin approach as the leading principle for implementation of the Act. IWRM, as per Article 83 m) of the Act, is the “ process that promotes coordinated development and management of water resources to maximize the economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems .”

The Act is a true management law in the sense that it lays out the i) principles, ii) Players and iii) approaches and mechanisms, institutional arrangements for planning, implementation, and monitoring progress towards sustainable management of water resources.

2. Water Related Acts

As mentioned above, until the Water Act was adopted the management of water resources was fragmented, addressed in different laws, and only focused on the operational level. The most important Acts that contain water related provisions are acts pertaining to land, forestry and nature conservation, mines and minerals management, electricity, waste, and environmental assessment and protection. The Acts regarding these water-related topics are briefly outlined below.

The National Environment Protection Act 2007

The National Environment Protection Act 2007 is the overarching environmental Act as stipulated in Article 2 which states that: “ All other Acts and regulations governing the use of land, water, forests, minerals and other natural resources shall be consistent with this Act. The provisions of all existing laws relating to environment, which are inconsistent with this Act, are hereby repealed .” The Act promulgates protection and conservation of the environment, water being an important part of it. It lays out the principles of environmental protection, establishes the powers and functions of National Environment Commission (NEC), its Secretariat and Competent Authorities. Chapter IV and V contain provisions for on maintaining environmental quality and Protection of forest, biodiversity, and ecosystem services. Chapter VIII establishes the procedures for environmental quality inspection and verification. Chapter IX deals with compliances requirements and defines offences and penalties.

The Environmental Assessment Act 2000

The Environmental Assessment Act of 2000 introduces the need for economic activities with significant environmental impacts to undergo environmental impact assessment. Article 33.1 of the Act empowers the NEC to adopt a list of projects that competent authorities are required to screen and issue environmental clearance. The NEC’s published the list of activities and the designated competent authorities for screening and issue of environmental clearance include water and water related project.1

The Forest and Nature Conservation Act 1995

The Forest and Nature Conservation Act 1995 has water related provisions concerning watershed management and prevention, minimization and remediation of erosion, pollution, and contamination of water. Article 10 forbids, except under license, manipulation of water sources and water courses by blocking, storing, or diverting river, stream, or irrigation channel. It also prohibits disposal of garbage and wastes into water bodies. In promoting soil and water conservation, Article 14 prohibits issue of license for felling or extraction of timber within 100 metres of riverbanks or edge of any water body or source. Article 29 empowers the Ministry responsible for Forestry to make rules and regulations as deemed necessary to protect soil, water, and wildlife resources. This is further elaborated in Forest and Nature Conservation Rules 2000 empowering the Department of Forest and Park Services to adopt and enforce such regulations as may be necessary to protect soil and water resources and to prevent, minimize and address erosion, pollution and contamination of soil and water.

The Land Act 2007

The Land Act 2007, as per Article 2, retains the provisions of the The Land Act 1979 concerning water channel and embankments and compensation on the crop damaged by cattle. The Land Act 1979 provisions on water include use of water for agriculture purposes granting farmers the permission to harvest water for irrigation on the condition that such use does not cause damage to other people’s property and plantations and that the amount of water availed does not exceed the capacity of the infrastructure to carry. The Act also obliges the farmers to maintain irrigation channels and structures irrespective of whether such structures affect other non-beneficiaries. The Act also provides for water sharing on the principles of mutual understanding, traditional customary practices, and equity based on size of land holding and amount of water available in the facility. Additional users may be accorded access to water from the depending on the availability of water in the channel. Article 267 in Chapter XII stipulates that the above provisions shall prevail till the Water Act is enacted.

Mines and Minerals Management Act 1995

The aspect of the Mines and Mineral Act 1995 that relates to water could be Article 4 that defines mineral as “any substance occurring naturally in or on the earth and having formed by or subject to a geological process and which can be obtained from the earth by digging, drilling, dredging, quarrying or by other mining operations”. The term ‘dredging’ used in this definition implies the scope of the Act covers riverbeds and water bodies.

The Electricity Act 2001

The Electricity Act of 2001 is directly related to water given that electricity in Bhutan is generated from use of water resources. It is for this reason that the Act contains specific provisions concerning water. Article 17.1 (xi) empowers the Minister (currently Minister of Economic Affairs) to grant permission to the license holder to acquire ownership or rights to land and water necessary to meet the purpose of the license. Under Article 52.1 (iv), a licensee is granted the rights to over private, public and government land and premises to ‘… divert any water way, lake, swamp, or marsh or to alter the bed, course or channel of any water way.’ Article 53.7 empowers the Bhutan Electricity Authority with the power to determine the Royalty on use of water and land resources.

The Waste Prevention and Management Act 2009

The Waste Prevention and Management Act 2009 contains provisions which relate to water. The purpose of the Act is to protect and sustain human health through protection of the environment by reducing the generation of waste at source, promoting segregation, reuse, and recycling of waste, and disposal of waste in an environmentally friendly manner. Water, being an important part of the environment, has a direct relation with this Act. Specifically, wastewater is subject to the provisions of the Act. Article 2 states that the Act extends to all forms of waste i.e., solid, liquid, or gaseous, hazardous, or non-hazardous, organic, or inorganic from various sectors.

Institutional Context

The institutional framework for IWRM in Bhutan comprises of agencies and ministries at the national level responsible for policy, planning and implementation, and local agencies/ government responsible for local operation. At the national level are the Gross National Happiness Commission along with the Gross National Happiness Commission Secretariat, The National Environment Commission along with the National Environment Commission Secretariat and the sector agencies. At the local level are the local governments, Water Users Associations, and the Dzongkhag Water Management Committee.

National level

Gross National Happiness Commission Secretariat (GNHCS)

The Gross National Happiness Commission is the national planning agency and an Institution that promotes an enabling environment for all Bhutanese to be happy. It is the secretariat that functions as the administrative unit. There are planning officers who support the secretariat with local and sectoral plans. Its policy and planning roles involve screening policies proposed by government line agencies, developing guidelines for national planning, setting sector Key Result Areas (KRAs) and KPIs, and reviewing and endorsing national vision documents and five-year plans that contain water related targets. GNHCS is also responsible for consolidating plans and priorities at national, district and Gewog levels, screening and approving project proposals from sectoral agencies, monitoring progress against plans through the online planning and monitoring system (PLaMS), liaising with Prime Minister’s office in defining targets for annual compacts with sectors, mobilizing resources in collaboration with Ministry of Finance and facilitating fund flow. The GNHCS also undertakes information, research and capacity building roles conducting research for development planning, developing monitoring, and reporting tools and building capacity of planning officers. It is the repository of information on all plans of Gewogs, Dzongkhags, Ministries, and other governmental agencies.

National Environmental Commission (NEC)

The NEC is the apex authority for the purpose of delivering policies, plans, programs, and monitoring water resource management in the country. It is the highest authority and decision-making body on all matters related to policies, plans and guidelines for managing environment and water resources.

The NEC is the main custodian of environmental and water resources management. The key role and purpose of the NEC are to develop policies, plan for water development, programs, and monitoring water resources management in Bhutan. Also, the NEC Secretariat (NECS) in consultation with competent authorities prepares and periodically update the National Integrated Water Resources Management Plan for the conservation, development, and management of water resources.

National Environment Commission Secretariat (NECS)

The secretariat is responsible for the day-to-day functions of the NEC. It consists of five divisions and has a District Environment Officer to carry out its functions at the district level.

Ministry of Agriculture and Forests (MoAF)

The Ministry of Agriculture and Forests (MoAF) is the competent authority for irrigation, watershed, and wetland management in Bhutan. It is responsible for development of irrigation systems and management of watersheds throughout the country. The Ministry’s Engineering Division is responsible for providing engineering services to local administrations for the design and development of irrigation systems. Specifically for watersheds, the Watershed Management Division under the Department of Forests and Park Services (DoFPS) is responsible for categorizing watersheds, preparing management plans, and implementing these plans in collaboration with stakeholders. The WMD was established in 2009 through an executive order by the Cabinet. The division was set up to have an integrated approach in watershed management and to implement functions and responsibilities mandated by the different policies and Acts. The WMD while implementing watershed management programs is also the focal point for wetlands, environment, climate change and range lands. With regard to watershed management, the WMD formulates policies and is guided by key Acts such as Forest and Nature Conservation Act 1995, the Water Act 2011, the Water Regulation of Bhutan 2014, Water Policy of Bhutan, Forest Policy 2011, Forest and Nature Conservation Rules and Regulation (FNCRR) 2017 and other relevant legislations of the country. For wetland management, the WMD has the mandate for planning, coordination and implementation of wetland management programs and their protection as per the Forest and Nature Conservation Rules and Regulations (FNCRR), 2017. The Water Act and the Water Regulation designates MoAF as the competent authority for wetland management in the country providing them the responsibility to develop and implement wetland management plans.

The MoAF is responsible for conserving and promoting sustainable utilization of water resources. They identify areas for conservation, protection, and management of watersheds. The ministry also implements the National Irrigation Policy and develops infrastructure for irrigation including the technologies for innovative ways to use water efficiently for irrigation.

The MoAF has the following responsibilities in watershed management:

Water Resources Management policy and planning role

- Develop and implement watershed and wetland management plans.

- Identify watershed areas that require protection, conservation, and management for sustainable supply of water.

Coordination and regulatory role

- Ensure the protection, conservation, and management of watersheds to sustain water supply and other environmental services.

- Promote payment for environmental services mechanism to support watershed management programs.

The Forest and Nature Conservation Rules and Regulation (FNCRR) 2017 stipulates that the DoFPS should carry out assessments of watersheds and its classifications in river basins by classifying them into critical, degraded, normal and pristine. This activity has to be done in consultation with local governments, communities, and other stakeholders in a participatory process. The DoFPS is also mandated to prepare and implement watershed management plans, formation of watershed management committees and monitoring and evaluation of the plan.

Ministry of Economic Affairs (MoEA)

The MoEA through the Department of Hydropower and Power Systems and the Department of Hydromet Services is responsible for promoting sustainable hydropower development weather water, climate, and other related environmental services to the various sectors. It facilitates integrated, regionally balanced, and optimal use of water for development of hydropower. The DHMS provides agro-meteorological information, hydro-meteorological data and GLOF warnings and alerts. The Department of Geology and Mines monitors, updates inventory and conducts research on glaciers and glacial lakes. The National Centre for Hydrology and Meteorology was established in 2016 and its mandate is to provide scientific and technical services in hydrology, water resources, meteorology, climatology, and cryosphere.

Ministry of Health (MoH)

The Ministry of Health (MoH) is responsible for monitoring quality of drinking water, as mandated by the Water Act and Water Regulation. It is responsible for the management of infrastructure, planning, monitoring, and implementation for drinking water and sewage in the rural regions of Bhutan in cooperation with local government and stakeholders.

Ministry of Home and Cultural Affairs (MoHCA)

Through the Department of Disaster Management, the MoHCA is responsible for disaster mitigation and relief especially during water related disasters like GLOFs.

The MoHCA develops public awareness by religious bodies about the water pollution caused by religious and cultural belief. The ministry monitors and warns the general public about GLOFs and carries out rescue and relief activities during disasters.

Ministry of Works and Human Settlements (MoWHS)

This Ministry is responsible for overall planning, implementation, and management of infrastructure for drinking water supply and wastewater for rural and urban areas in collaboration with local governments. It is mandated to prepare its development plans in consultation with local governments and to mainstream water resources management into its policies, plans and programs.

Sub-National

District Development Councils

Local governments in Bhutan have a key role to play in operationalization of IWRM. For example, the Dzongkhag Tshogdu identifies elements under the national water sector plan to be implemented at the local level, plan water facilities for drinking water supply and irrigation, and incorporate the National Irrigation Plan in into its local water resources management plan. Under the Water Regulation, the Dzongkhag Water Management Committee is responsible for the proper and effective protection and management of water resources at the Dzongkhag level.

They carry out the planning and management of irrigation and drinking water facilities at the district level in collaboration with the ministries. The oversee the procurement processes for the construction of drinking water and irrigation facilities. They also monitor use of and maintenance of water facilities, they are the reporting body on water facilities to the local authorities.

Watershed management requires a concerted effort that encompasses various sectors with a multi-disciplinary approach in planning and implementation. The WMD therefore faces a challenging responsibility of coordinating and planning with various stakeholders, government ministries, departments, agencies, and corporate entities. Activities in the watershed area that are linked to the mandate of these agencies require them to provide guidance regarding policy or any other technical support prior to implementation of the activity.

The Dzongkhag administration involving its different sectors such as agriculture, livestock, planning, and engineering are also engaged in watershed management. There is also the participation of specific officials from the Gewog administration. As watershed management activities are incorporated into area-based planning framework, local governments are a critical stakeholder in watershed management. They have the responsibility of ensuring identification of watershed management issues and to take remedial measures. They are involved right from the inception stage to completion of watershed management activities within their jurisdiction and have the responsibility to integrate the interventions and measures in their respective annual and five-year plans. Budgetary support from the central to the local governments comes under a general head of accounts. However, with respect to watershed management there is no specific staff for this activity either in the Dzongkhag or the Gewog local administration.

River Basin Committees

River Basin Committees are mandated by the Water Act for the proper management of water resources. Its responsibilities are to prepare the RBMP, foster community participation, monitoring and reporting to NEC, data management and resolution of cross-sectoral and trans-boundary water management issues. Water User Associations (WUAs) are groups of water users of a water facility or source. According to the Act, these are to be established across the country except in Thromdes. Ministry of Education (MoE) and civil society organizations are also integral part of the IWRM strategy in Bhutan.

The committee plans and prepares the river basin management plan and monitors the quality of the water in the rivers. The committee reports directly to the NEC. A River Basin Committee has been formed for the Wangchhu basin in 2016.

Water User Associations

Traditionally in Bhutan, community/ user groups were formed around rural communities living near natural water resources. They functioned according to traditional and customary rights that governed their relationship among them and the water resource. This was more of an informal framework with unwritten codes and rules to guide them. With the emerging challenges of increased population, water shortages and scarcity of water source, their role is even more critical today. The concept of WUAs was introduced through donor assisted rural water supply and irrigation programs of the government. In a way the WUA concept along with the WUA byelaws for election of office bearers and operational norms were embraced by the beneficiary committees under some obligation to avail benefits provided through the water supply and irrigation schemes.

Over the years there have been different agencies and Acts and legislations that independently provided for formation and registration of community groups. The Cooperatives Act of Bhutan 2009, Cooperatives Rules and Regulations of 2010 and the Land Act of Bhutan 2007 in their own way promoted farmers groups. The Agriculture Engineering Division under the Department of Agriculture (MoAF) entrusted user groups with the responsibility of taking over, operating, and maintaining irrigation facilities. The Public Health and Engineering Division (PHED) under the Ministry of Health promoted community participation in the monitoring and maintenance of rural water supply schemes. User groups were mainly formed to implement water safety plans to address health concerns related to water borne diseases.

The Water Act of Bhutan 2011 and Water Regulation 2014 took a step further to harmonize the earlier policies and laws and bring in a mandate for the WUAs to have greater significance in the sustainable management of water resources in the country. This legislation brought both drinking water and irrigation water facilities within the legal purview as responsibilities of the WUAs. With the support of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the Royal Government of Bhutan sought to further build upon the existing mandates governing WUAs by bringing out guidelines through an agreement with the Department of Agriculture along with a proposed guideline on the formation and registration of water users associations in 2016. The legal mandates and the proposed guidelines aim to strengthen WUAs to make them more effective in the management of water sources both for irrigation and drinking water.

Chapter 11 of the Water Act acknowledges the potential role of Water User Associations in sustaining water sources and water supply services in rural areas. It is for this reason that the Act creates the legal space for community participation in water resource management. With the objective of fostering community ownership and sustainability of water supply services, beneficiaries of a specific water source have the option of organizing themselves into a Water Users Association (WUA) primarily for the purpose of maintaining and management of water supply for their needs. The Water Regulation requires the formation of WUAs (Water User Associations) to be registered with the concerned Gewog Administrations. The protocols for formation and registration of the WUAs is provided in the Water Regulation and further elaborated in the Guidelines for Formation and Registration of WUAs.

More on WUAs…

The Water Act of Bhutan 2011 mandates that “Any group of beneficiaries using a particular water source for their water supply needs may form a Water Users’ Association to maintain the water source and to manage water supply services. This is further spelt out in the Water Regulation, 2014 which describes the formation, registration, powers, and functions of WUAs with an overall emphasis to make them important drivers in securing the overall objective of water security in the country. The Regulation emphasizes that WUAs can be involved more deeply in managing water sources by coordinating with local administrations and river basin authorities. This aims to provide WUAs a greater role in local water resource management. The regulation seeks to increase the capacity of WUAs to coordinate with local administrations like the Gewog and Dzongkhags in the field of technical assistance, assessing water availability while at the same time ensuring new users are brought into the WUA. It also stresses on the concept of water sharing by the users when supply is scarce. WUAs are also recommended to invite technical resource persons such as the district forest officer or district rural engineer or others from the local administration to contribute to WUA meetings.

There is no comprehensive inventory of WUAs in the country. As per the Water Act 2011, the NEC is the agency entrusted with the responsibility of promulgating WUAs. However, no WUAs have been formed under direct initiative of the NEC. From the pilot experiences in the Wangchhu basin, the WUAs were created by the health and agriculture sectors for rural water supply and irrigation purposes, respectively. Many of the WUAs established earlier are not functional. There is no existing system of registering and monitoring the functionality of WUAs. The WRCD, NECS has prepared the Guidelines for formation and registration of WUAs, which remains to be formally adopted and applied.

With a view to enlarging the provisions of the Water Regulation, 2014, particularly to provide greater clarity on the procedures for formalization and regulation of WUAs, guidelines on the formation and registration of water users associations were proposed in 2016. A key element of the guidelines was for the WUAs to collaborate with Gewogs and Dzongkhag administrations and River Basin Committees (RBCs) in planning and implementing activities to achieve the National Integrated Water Resources Management Plan (NIWRMP) objectives (Guidelines, 2016). The focus of the guidelines was also to bring about a mechanism for sound institutional design and self-governance of water management. This also involves encouraging existing viable practices and bringing in novel approaches (ibid). The guidelines also recommend WUAs, the local administrations and the central agencies to work in a collaborative and sustained manner so as to generate key inputs from the local level into the respective agency plans enabling them to be more viable for implementation. The National Environment Commission Secretariat (NECS) has taken on the responsibility of framing the guidelines and the further formalization of the WUAs. The initiative has been piloted in the Wangchhu Basin with its implementation over the past one year. The aim is to learn through the implementation experience from the Wangchhu basin and accordingly reformulate the guidelines and protocols to be finally operationalized.

The Water Regulation 2014 stipulates that all users (members of households using water from a facility or source or people using irrigation water facility) are members of Water Users Association (WUA). Further, if members are users of both drinking water and irrigation facilities the WUA will be for both the purposes.

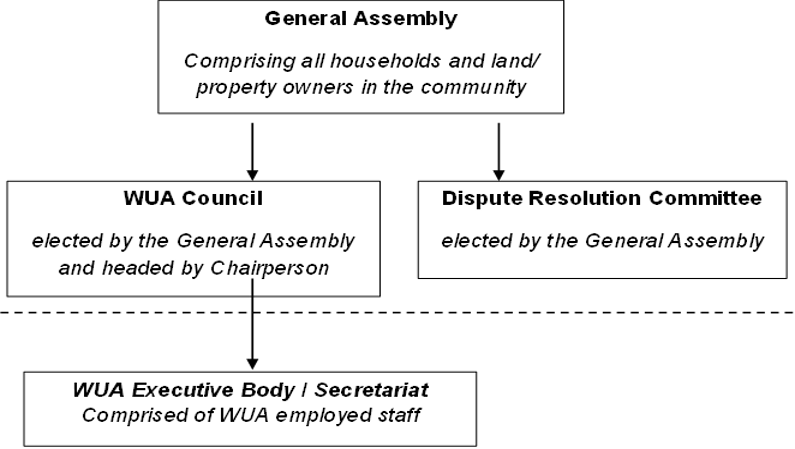

The Gewog administration is critical to the establishment of WUAs within their jurisdiction. The Water Regulation mandates a chairperson and two members with functional literacy as core composition of the WUAs. The guidelines further detail that there should be a secretary, an accountant, auditors, executive members and at least two water guards for management purposes. The basic organizational structure of the WUA as per the guidelines is given below:

Organizational structure of WUAs

The Gewog administration has to guide the community in processing the application for registration and formation of WUAs. It keeps a registry of the registered users/WUAs within its jurisdiction. Information of registered WUA with its name and address, date of registration, the registration certificate number, the founding council members, names of the office bearers and the chairperson along with their status of tenure and the current operational status of the WUA have to be stated. The Gewog administration has to facilitate the issuance of water abstraction permits after assessment, and if they lack expertise and technical know how it can seek support from the Dzongkhag administration. The Gewog administration in general and the Wangchhu Water Security Index (WWSI) in particular are the current repositories of the information database regarding WUAs in Bhutan.

Currently, a Chhusup (literally translated as water guard) is entrusted by the members of a community with the responsibility to ensure water supply for drinking and/or irrigation. This concept of Chhusup became integrated into the WUA concept that was introduced through rural water supply schemes and irrigation projects. While many WUAs, particularly those that are consistently facing water supply issues tend to embrace this concept. The role of Chhusups either rotates among the members of the group or the members appoint a person who is remunerated through contributions from the members. Not all WUAs have Chhusups.

The Gewog agriculture extension supervisors assist in the process of social mobilization in irrigation (renovation and construction works) and in the formation of WUAs in respective areas/sites. Under irrigation, the physical infrastructure assets like pumps, generators, storage tanks and so on, are handed over to the beneficiaries/users/WUAs, after the completion of construction and installation. They own and manage these irrigation assets while the local governments provide technical and financial support. The WUAs are responsible for allocation and provision of irrigation water to the beneficiaries/farmers using the irrigation assets/facilities. This allocation of water and provision has to be done by the WUAs in an equitable manner. However, the allocation of water in most cases by WUAs is done based on traditional water rights. Rural communities continue to employ traditional norms and customary practices in water sharing for household water supply and irrigation. The Water Act and its Regulation recognize such traditional water rights only to the extent that such rights do not infringe on water need of other downstream and upstream community and that the mechanisms result in fair and equitable distribution of water (see article 40 of Water Regulations, 2014).

With regard to operation and maintenance, WUAs in the form and structure created for rural water supply services and irrigation programs are primarily supported by government projects especially for locally unavailable material needs such as pipes, cement etc. Local members of the WUA contribute labor. There are also WUAs that collect fees from members to supplement O&M expenses. However, this is not consistent across all WUAs.

The Gewog administration has to guide the community in processing the application for registration and formation of WUAs. It keeps a registry of the registered users/WUAs within its jurisdiction. Information of registered WUA with its name and address, date of registration, the registration certificate number, the founding council members, names of the office bearers and the chairperson along with their status of tenure and the current operational status of the WUA have to be stated. The Gewog administration has to facilitate the issuance of water abstraction permits after assessment, and if they lack expertise and technical know how it can seek support from the Dzongkhag administration. The Gewog administration in general and the Wangchhu Water Security Index (WWSI) in particular are the current repositories of the information database regarding WUAs in Bhutan.

Currently, a Chhusup (literally translated as water guard) is entrusted by the members of a community with the responsibility to ensure water supply for drinking and/or irrigation. This concept of Chhusup became integrated into the WUA concept that was introduced through rural water supply schemes and irrigation projects. While many WUAs, particularly those that are consistently facing water supply issues tend to embrace this concept. The role of Chhusups either rotates among the members of the group or the members appoint a person who is remunerated through contributions from the members. Not all WUAs have Chhusups.

The Gewog agriculture extension supervisors assist in the process of social mobilization in irrigation (renovation and construction works) and in the formation of WUAs in respective areas/sites. Under irrigation, the physical infrastructure assets like pumps, generators, storage tanks and so on, are handed over to the beneficiaries/users/WUAs, after the completion of construction and installation. They own and manage these irrigation assets while the local governments provide technical and financial support. The WUAs are responsible for allocation and provision of irrigation water to the beneficiaries/farmers using the irrigation assets/facilities. This allocation of water and provision has to be done by the WUAs in an equitable manner. However, the allocation of water in most cases by WUAs is done based on traditional water rights. Rural communities continue to employ traditional norms and customary practices in water sharing for household water supply and irrigation. The Water Act and its Regulation recognize such traditional water rights only to the extent that such rights do not infringe on water need of other downstream and upstream community and that the mechanisms result in fair and equitable distribution of water (see article 40 of Water Regulations, 2014).

With regard to operation and maintenance, WUAs in the form and structure created for rural water supply services and irrigation programs are primarily supported by government projects especially for locally unavailable material needs such as pipes, cement etc. Local members of the WUA contribute labor. There are also WUAs that collect fees from members to supplement O&M expenses. However, this is not consistent across all WUAs.

WUA guidelines at present per se do not mandate the inclusion of women in a specific manner. It is left to the initiative/willingness of the respective households or groups that form the WUA. The Department of Agriculture and the Dzongkhag/ Gewog administrations stress on the importance to involve more women to participate and join WUAs as committee members.

Federations are the coming together of different WUA along the same water-source, who are its users and have the objective of conservation and preservation of the sources, resolve common concerns, and also manage the influx of effluents into the source. These are planned as larger groups of WUAs that have a common objective and seek to maintain the water sources in a clean and sustainable manner thereby benefitting all the users, new as well as old.

A sustained application of the WUA guidelines even in the Wangchhu basin is yet to take place.

The basin level water security index (WSI) which is part of the Bhutan Water Security Index is one of the mechanisms for the maintenance of the local water data base. Currently it is developed for the Wangchhu basin and is called the Wangchhu Water Security Index (WWSI). The data for this is collected based on five key dimensions. The data is collected at the Chiwog level and entered into the WWSI data base system that generates reports regarding the status of the water security in that area. It is planned to develop this WSI for other management basins using the same process. The WWSI system also has information on the WUAs in the Wangchhu basin.

As per the WUA guidelines, the Gewog administration and the concerned staff are responsible for monitoring WUA and its operation. The administration of the Gewog is responsible for the establishment of the WUA within their jurisdiction. The Gewogs have to maintain a registry of the different WUAs in the local database in the Gewogs. According to the guidelines, the Gewog Administrative Officer (GAO) is the Registrar of the WUAs in every Gewog administration. Gewogs can hold WUA accountable if it exceeds certain developmental activities that strains water capacity and its catchment. The Gewog administration has to ensure that the WUA is operating according to the laws stipulated in the water regulation. WUAs have to submit an annual report of its operation, status, and other details to the Gewog administration. The Gewog/Dzongkhag administration can establish byelaws for the smooth working and other operational aspects of the WUAs.

A grievance redressal mechanism (GRM) has also been proposed in the guidelines for feedback and recording grievances from each registered WUA. Issues relating to equitable water sharing, equal treatment of members and information on the induction of new members are some of the key points that the GRM platform seeks information on. The Gewog administration can initiate a process to penalize or provide a notice of suspension or even cancellation of any WUA registration if there is found to be non-compliance by WUAs in following mandated guidelines or byelaws.

WUAs are increasingly expected to play a critical role in the resolution of disputes among water users. The Water Regulation mandates the appointment of a facilitator to negotiate conflicts along with a process of voting among members to reach a decision which currently is brought to the Gewog for an amicable resolution. The guidelines stipulate a strong role for the Dzongkhag Water Management Committee (DWMC) to address concerns of WUAs and its members. The DWMC works with the respective administration and the NEC to seek resolution to any matters of dispute.

The Water Regulation 2014 provides for WUAs to “determine and adopt water user fees that are commensurate with the services rendered by its members”. The financial aspect has not been clearly articulated in the guidelines, especially with regard to how fee and charges have to be mobilized. In the Wangchhu Basin pilot that is currently being implemented, fees are collected from among the members of the WUA. The fees collected are used for water source maintenance, operation, costs of infrastructure and the service providers. The fee collection process is rotated amongst the members of the group. The fee collection process and the ultimate use have not been standardized in terms of what manner it is to be utilized or what share is to be used for maintenance activities of the WUA infrastructure. Presently, while in some cases the money collected/budget at hand is maintained by the Gewog administration, in others it is maintained by the WUAs themselves. With respect to WUAs on irrigation, fees are charged annually during the general meeting and the funds collected are kept as a maintenance fund in accordance with the WUA constitution and byelaws. The fees collected are both in cash and in kind.

Key challenges

Formalization of WUAs: Currently, on the ground, the WUAs still tend to be more in the realm of traditional and customary practices for drinking water, water safety plans and irrigation schemes. The lack of formalization has been pointed out as resulting in their non-systematic functioning. Wherever formed, either as required by projects or as entry points for the use of a water resource, WUAs have had a staggered existence, with its sustainability driven by the need and character of the users. Most of the WUAs are now non-functional after being established as part of development projects that have since been completed. There are some that are functional, actively looking after the maintenance of the infrastructure, operation and management of the water sources and related infrastructure.

Capacity constraints: There is low technical and financial capacity among the beneficiaries and users of the WUA communities. This could have an adverse impact on the planning, management, and protection of the respective water sources that they are attached to. Currently there are limited interventions to increase awareness and to provide training especially on roll out of water safety plans and/ or rural water supply projects.

Lack of monitoring: Currently, there is weak monitoring by Gewogs over the operation of the WUAs.

User fees and financial resource mobilization: There is inadequate institutional mechanism for mobilization of resources and for collection, maintenance and audit of fees collected. As pointed out earlier, the situation of some WUAs maintaining their accounts with Gewogs while others maintaining and managing it by themselves is an indicator of the absence of a standard protocol or regulation for establishment and operation of WUAs. There is no uniform standard applied with regard to collection of user fees in WUAs in the Wangchhu basin.

Database on WUAs: While Gewogs do maintain a list of the WUAs within their jurisdiction they are neither exhaustive and are not updated with respect to their operational status, members, and office bearers. A comprehensive database of WUAs in the Wangchhu river basin is yet to be developed. There is an absence of a functional, incentivized institutional mechanism with respect to the WUAs, leaving them at times with a lesser sense of purpose that hastens their disintegration. While the intent of the establishment of WUAs is clear, there is a lack of a strong institutional framework and any sort of allied supporting incentive mechanism. This aspect among others is what the NECS is working on and hopes to remedy with the implementation and the learning from the implementation of the Wangchhu basin pilot. The potential trajectories of WUAs and RBCs depend greatly on the experience and learning of the Wangchhu Basin Committee and the Wangchhu Basin Management Plan.

Civil Society Organizations

This is made of the Royal Society for the Protection of Nature (RSPN), the Tarayana Foundation, and the Bhutan Water partnership in the water sector. They spread awareness to the local communities about water related issues such as conservation, pollution, misuse of water and promote the efficient use of water.

Regional

South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation

The objectives of the Association as outlined in the SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation) Charter is to promote the welfare of the peoples of South Asia and to improve their quality of life; to accelerate economic growth, social progress, and cultural development in the region and to provide all individuals the opportunity to live in dignity and to realize their full potentials; to promote and strengthen collective self-reliance among the countries of South Asia.