APPENDIX A. PA Management Categories as Defined by IUCN

The appendices include a suite of tools and practical information that will help practitioners to identify, screen, prepare for, and establish CMPs.

Table A.1 PA Management Categories

|

Protected Area Management Categories |

|

|

PA definition: “A clearly defined geographical space, recognized, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values.” |

|

|

i) (a) Strict nature reserve |

Strictly protected for biodiversity and also possibly geological/ geomorphological features, where human visitation, use, and impacts are controlled and limited to ensure protection of the conservation values |

|

i) (b) Wilderness area |

Usually large unmodified or slightly modified areas, retaining their natural character and influence, without permanent or significant human habitation, protected and managed to preserve their natural condition |

|

ii) National park |

Large natural or near-natural areas protecting large-scale ecological processes with characteristic species and ecosystems, which also have environmentally and culturally compatible spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational, and visitor opportunities |

|

iii) Natural monument or feature |

Areas set aside to protect a specific natural monument, which can be a landform, sea mount, marine cavern, geological feature such as a cave, or a living feature such as an ancient grove |

|

iv) Habitat/species management area |

Areas to protect particular species or habitats, where management reflects this priority. Many will need regular, active interventions to meet the needs of particular species or habitats, but this is not a requirement of the category |

|

v) Protected landscape or seascape |

Where the interaction of people and nature over time has produced a distinct character with significant ecological, biological, cultural, and scenic value: and where safeguarding the integrity of this interaction is vital to protecting and sustaining the area and its associated nature conservation and other values |

|

vi) PAs with sustainable use of natural resources |

Areas that conserve ecosystems, together with associated cultural values and traditional natural resource management systems. Generally large, mainly in a natural condition, with a proportion under sustainable natural resource management (NRM) and where low-level non-industrial natural resource use compatible with nature conservation is seen as one of the main aims |

Source: Dudley 2008.

APPENDIX B. Global PPP Market Assessment

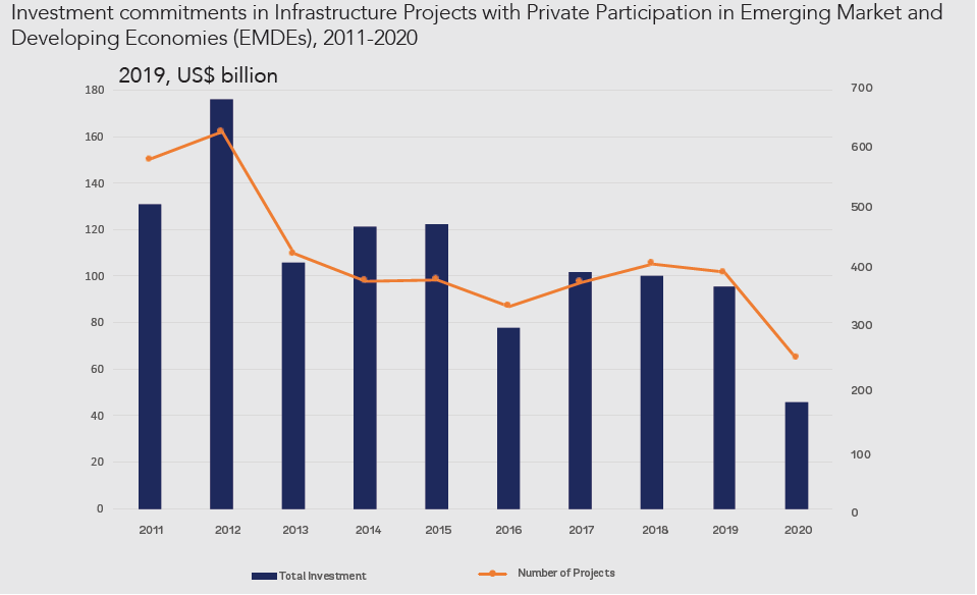

While there is no global database that tracks PPPs across all sectors and regions, the World Bank tracks private investments in infrastructure. In 2019, a total of $96.7 billion in private investments were committed towards 409 infrastructure projects in 62 low- and middle-income countries (WBG 2020a). This represents a three percent decline compared to 2018, which can be explained by market volatility and reduced investments in energy. In 2020, due to the impacts of COVID-19, investments dipped to $45.7 billion across 252 projects, a 52 percent decrease from investment levels in 2019 (see Figure B.1).

Figure B.1 Investment Commitments in Infrastructure Projects with Private Participation in EMDEs, 2011–2020

Source: World Bank 2021.

In 2019, transport (roads, railways, ports, and airports) was the largest sector, accounting for half of global private investments. Energy (natural gas and electricity) was the second largest sector, representing 41 percent of investment commitments. In 2020, transport sector investment commitments were the lowest in the past decade, reflecting the massive changes in movement caused by lockdowns.

The number of countries receiving private investments in infrastructure in 2019, 62 countries, was the highest number in the last decade. Nearly 40 percent of investments occurred in Asia, though investments in Latin America and the Caribbean increased. China, Brazil, India, Vietnam, and Russia received the highest levels of investment. In Sub-Saharan Africa, Ghana and Nigeria were the two biggest investment destinations, with $1.5 billion and $1.1 billion, respectively. Sudan, Chad, the Comoros, Mauritania, Cabo Verde, and Malawi recorded their first private investment infrastructure projects in five years in 2019.

APPENDIX C. Description of PPP Legislation in Selected Countries in Africa

Table C.1 PPP Legislation in Selected African Countries

|

Country |

PPP Legislation |

PPP Legislation |

Date |

PPP Unit |

Unit Overseeing PPP Entity |

|

Ethiopia |

Yes |

PPP Policy Document and the Public Private Partnership Proclamation No. 1076/2018 |

2018 |

Yes |

Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation |

|

Guinea |

Yes |

032 / Public Private Partnerships Act |

2017 |

Yes |

Ministry of Finance |

|

|

|

Decree 041, the application of the 2017 PPP Act |

2021 |

|

|

|

|

|

Decree 042, the organizational framework applicable to 2017 PPP Act |

2021 |

|

|

|

Kenya |

Yes |

The Public Private Partnerships Act |

2013 |

Yes |

National Treasury and Planning |

|

|

|

Public Private Partnership Amendment Bill |

2017 |

|

|

|

Malawi |

Yes |

Public-Private Partnership Act |

2011 |

Yes |

PPP Commission under the Office of the President |

|

Mozambique |

Yes |

Law No. 15/2011, PPP Law |

2011 |

Yes |

Unit under the Ministry of Finance |

|

|

|

Decree No. 16/2012, June 4, PPP Regulations |

2012 |

|

|

|

|

|

Decree No. 69/2013, 20 December, came into force on the year of publication. |

2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

Decree Law No. 15/2010, May 24, governs PPP procurement procedures, on a subsidiary basis |

2010 |

|

Government entities or ministries or municipalities, responsible for the sector of the project. Financial framework, supervision exercised by the Ministry of Economy and Finance |

|

Rwanda |

Yes |

Law No.14/2016 of 02/05/2016 Governing Public Private Partnerships |

2016 |

Yes |

Rwanda Development Board |

|

Uganda |

Yes |

The Public-Private Partnerships Act |

2015 |

Yes |

Ministry of Finance |

|

Zambia |

Yes |

The Public-Private Partnership Act |

2009 |

|

|

|

|

|

Public-Private Partnership (Amendment) [No. 9 of 2018 223) |

2018 |

Yes |

PPP Unit under Zambia Development Agency (ZDA)-PPP Council |

|

Zimbabwe |

No |

2010 PPP Policy. 2004 PPP Guidelines |

|

No |

PPPs administered by the Ministry of Finance with the other relevant Ministry (Ministry of Environment, Water and Climate for Protected Areas) |

APPENDIX D. Case Studies

Table D.1 Key Aspects of Nine CMP Case Studies

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

|

|

Akagera NP |

Dzanga-Sangha NP |

Gonarezhou NP |

Gorongosa NP |

Liuwa Plain NP |

Kruger National Park |

Nouabale-Ndoki NP |

Simen Mountain NP |

Yankari NP |

|

Figure |

D.1 |

D.2 |

D.3 |

D.4 |

D.5 |

D.6 |

D.7 |

D.8 |

D.9 |

|

Government Partner |

RDB |

Ministry of Water and Forest, Hunting and Fishing |

ZPWMA |

Government of Mozambique |

DNPW |

SANParks |

Ministry for Forest Economy |

EWCA |

Bauchi State Ministry of Culture and Tourism |

|

NGO Partner |

African Parks |

WWF |

FZS |

Gregory C. Carr Foundation |

African Parks |

Community: Makuleke Community |

WCS |

AWF |

WCS |

|

Country |

Rwanda |

Central African Republic |

Zimbabwe |

Mozambique |

Zambia |

South Africa |

Congo |

Ethiopia |

Nigeria |

|

Model |

DM |

BCM |

ICM |

IM |

DM |

IM |

DM |

BCM |

BCM |

|

Size Km2 |

1,122 |

4,580 |

5,053 |

6,777 |

3,369 |

265 |

3,922 |

220 |

2,250 |

|

CMP Signed |

2010 |

2019 |

2017 |

2018 |

2004 |

1999 |

2014 |

2017 |

2014 |

|

Agreement Duration |

20 |

5* |

20 |

25 |

20 |

50 |

25 |

15 |

15 |

|

# Year to develop CMP |

3 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

|

Years NGO worked in PA prior to CMP |

0 |

30 |

9 |

4 |

0 |

N/A |

20 |

5 |

5 |

|

NGO Investment $ million |

35 |

.5-1 million / year |

27 |

85 |

20 |

1 |

25.5 |

5 |

3 |

|

Staff Size |

273 |

150 |

270 |

700 |

127 |

~100 |

196 |

N/A |

100 |

|

Annual Budget $ million (including CAPEX) |

3.25 |

5.5 |

5 |

13.7 |

3 |

N/A |

5.3 |

1 |

0.5 |

|

Notes |

|

*Option to extend as foundation. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure D.1 Akagera NP Case Study

Figure D.2 Dzanga-Sangha PA Case Study

Figure D.3 Gonarezhou NP Case Study

Figure D.4 Gorongosa NP Case Study

Figure D.5 Liuwa Plan NP Case Study

Figure D.6 Nouabale-Ndoki NP Case Study

Figure D.7 Makuleke Contractual Park Case Study

Figure D.8 Simien Mountains NP Case Study

Figure D.9 Yankari NP Case Study

APPENDIX E. Description of CMP Models

The Toolkit focuses on three CMP models — bilateral, integrated, and delegated (the latter two collectively referred to as co-management). For a description of financial and technical support see Baghai et al. 2018 .

Table E.1 Bilateral, Integrated, and Delegated CMP Descriptions

|

|

|

Co-management |

|

|

|

Bilateral |

Integrated |

Delegated |

|

Description |

|

|

|

|

|

The government authority and partner agree to co-manage the PA, frequently with two leaders, generally a government warden or conservator (park manager) and the partner’s technical advisor (TA) or manager (partner manager) |

A joint entity and SPV (foundation, non-profit company) is created in the host country, and management is “delegated” from the government authority to that entity |

A joint entity or SPV (foundation or non-profit company) is created in the host country |

|

|

No independent entity is created to manage the park, except a management and/or oversight committee |

Unlike the delegated model, this entity is characterized by 50-50 power-sharing, rather than being led by the partner |

Management of the park is fully “delegated” from the government to the SPV |

|

|

|

|

The governance is shared, but authority for the PA management is allocated to the partner |

|

Governance |

|

|

|

|

|

A governance body is created with representation from government and the partner |

Board with 1:1 representation; often with co-chairs representing each party and/or each party chairs on a rotating basis |

The partner appoints the majority of board members, including the chairperson

There are examples, such as Odzala NP in the Republic of Congo, where the NGO nominates other representatives from civil society and the private sector, so the partner may not have the majority but their nominees represent the majority |

|

|

Decision-making is by consensus |

If there is an even number on the board, it may have an independent board member with particular technical expertise, a representative of a stakeholder community, or in the event of a tie, the casting vote may depend on the topic (for example, if it pertains to law enforcement, the PA authority has the casting vote, and if it pertains to funding, the partner may have the casting vote) |

The government appoints a minority of board members |

|

|

|

The board appoints the senior executive management team |

|

|

Management |

|

|

|

|

|

The government typically appoints a PA manager, as is customary, with authority for the PA (Salonga CMP in the Democratic Republic of Congo is an exception where the NGO appoints the manager) |

The PA management team is led by the PA manager, who is jointly selected by the parties |

The partner appoints the park manager, after liaising with government |

|

|

The PA manager works alongside the partner’s manager on the ground |

The PA manager’s “second in command” is often someone from the wildlife authority, and specifically charged with overseeing law enforcement |

The PA manager has authority over the PA, including hiring and firing of staff |

|

|

Together the warden and TA form a management team (which may include other senior departmental staff as well) |

The PA manager has authority over the PA, and in consultation with the senior management team, has the ability to hire, transfer, and discipline staff |

The PA manager’s “second in command” is often someone from the local wildlife authority |

|

|

The two leaders collaborate, but may lead different departments on a daily basis |

All PA authority staff are managed under the SPV. New contracts are issued to qualified staff under the SPV where appropriate and some government and NGO staff area seconded to the SPV

Secondment is defined as when an employee is temporarily transferred to another department or organization for a temporary assignment. |

All PA authority staff are managed under the SPV. New contracts are issued to qualified staff under the SPV where appropriate and some government and NGO staff area seconded to the SPV |

|

|

Generally, the PA manager is responsible for political representation, government and community relations, and law enforcement |

|

|

|

|

Generally, the partner’s manager will take the lead on operational, planning, and technical activities |

|

|

Source: Baghai et al., 2018; Baghai 2016; Lindsey et al., 2021.

APPENDIX F. CMP Best Practice

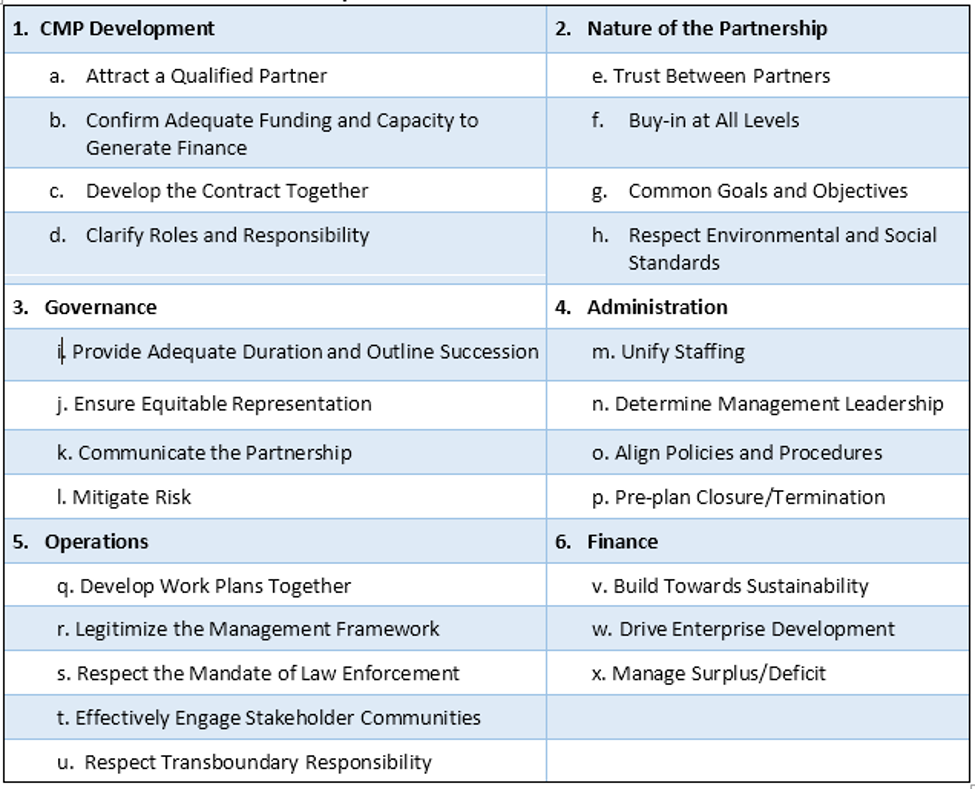

When developing, managing, and ending a CMP, governments and partners should consider a number of best practice principles. These 24 core principles are based on best practice and organized under six core pillars: CMP Development; Nature of the Partnership; Governance; Administration; Operations; and Finance.

Table F.1 Six Core Pillars of CMP Best Practices

Source: Adapted from Conservation Capital 2017.

1. CMP Development

a. Attract a Qualified Partner

The selection of a qualified partner with the requisite skills and experience is fundamental to the success of a CMP. Sections 5.5 and 5.7 outline a process for vetting and selecting a qualified partner. This is fundamental in any CMP. The PA authority is engaging in a CMP to fill certain gaps in their management structure. The very nature of a CMP is to provide a value addition to the PA authority; therefore, the PA authority should be clear on the objectives and the skills needed to achieve these objectives in order to select the appropriate partner.

b. Confirm Adequate Funding and Capacity to Generate Finance

The ability to financially execute a management agreement is fundamental to its success. Developing a proper CMP can take years. Going through this process only to later find that there is not adequate funding or the ability to generate revenue wastes already strained resources. As part of the partner selection process outlined in Sections 5.5 and 5.7, there should be due diligence and verification of start-up funding. Partners should provide documentation of verifiable donor pledges for start-up funding. The “intention” to approach certain donors is not adequate. Longer term funding will also be generated by the business plan and revenue development model; therefore, the quality of the business plan (see Appendix J) as well as the partners’ capacity to execute revenue models is a key aspect of partner due diligence.

c. Develop Contracts Together

Contracts should be developed collectively to foster collaboration, develop joint ownership, and avoid confusion over content. Governments and partners should try to develop CMP templates that based on contract best practice that can be adapted for the focal PA. It is important that principles are clearly agreed on between the partners, and that there are appropriate contractual terms around those principles. From there, a contract can be adapted to particular circumstances. Each partner needs to be comfortable and fully aware of the content of the contract. Joint-development and discussion provides clarity on why certain aspects are included in the agreement and can help avoid unnecessary delays due to misinterpretation.

d. Clarify Roles and Responsibilities

CMP agreements must be explicitly clear about roles, responsibility, reporting lines, and accountability to avoid confusion and conflict. (Appendix P includes a description of roles and responsibilities to include in the contract.) One of the greatest sources of conflicts in CMP is confusion over roles and responsibilities.

Responsibility and ownership of assets is a key issue to clarity at the onset of the partnership, including the basis upon which existing and new movable and immoveable operating assets will be treated at the commencement, during, and the end of the term. Recommendations for how this is managed are included in Appendix P.

e. Trust Between Partners

CMPs can have solid contracts, suitable funding, and a highly experienced partner. However, if there is not trust between the partners, it simply will not work. Developing trust takes time. This can be developed while a partner provides technical and financial support or during the development of the CMP agreement. Mechanisms should be put in place to quickly mitigate conflict that might lead to mistrust between the partners.

f. Buy-in at All Levels

Transparency and open discussion about the CMP development process is critical to ensuring buy-in at all levels. A CMP driven from the top (ministry or even higher) without buy-in at local level risks operational challenges and the undermining of the partnership in the field. Given hierarchies within wildlife authorities, the field teams may not communicate their concerns, but can very easily undercut the partnership in the field. Likewise, a CMP driven from the PA level or by a donor without legitimate buy-in from HQ risks political meddling. Transparency and open discussion about the goals, process, and means of measuring success is vital and will help avoid conflict. In addition, written endorsements from various levels within government will help document consultation and communication.

Sometimes there is a sense that because a CMP is in place, the government does not need to do much. Government’s role and ability to support CMPs — even delegated ones — is critical. This can be political support, fundraising support, providing permissions and legal approvals for import of equipment, and work permits. All of this requires support and buy-in.

g. Common Goals and Objectives

Both parties need to be moving toward the same objectives and goals and share a common vision. This underpins the operations and the direction of the partnership. The government wants to select a partner who shares its mission and ethos. If for example, the government wants to use a CMP to build internal capacity, they want a partner who believes this is the best approach for the PA and is not going to undermine this to maintain presence. The partners should discuss a shared vision and these aspects should be documented in the CMP agreement. Targets and indicators of success should reflect these common goals and objectives. In addition, the specific goals and objectives should be included in the GMP.

h. Respect ESS

ESS are a set of policies, standards and operational procedures designed to first identify and then, following the standard mitigation hierarchy, try to avoid, minimize, mitigate, and compensate when necessary adverse environmental and social impacts that may arise in the implementation of a project. The partners should jointly agree on a comprehensive framework that enables staff and project developers and managers to clearly identify, avoid, minimize, and mitigate social and environmental adverse impacts (see Chapter 6).

3. Governance

IX. Provide Adequate Duration and Outline Succession

The duration of the CMP depends on the PA and the PA authority goals. A CMP can be used as an interim (15-20 year) management tool to help a PA authority develop capacity along with the systems and structures needed for the PA authority to run the PA in the long-term. Alternatively, a government may view a CMP as a long-term and in some cases a more permanent solution, without the intention of evolving the PA management back to the PA authority. This decision is vested with the government for national PAs and either way, intentions should be explicit in the beginning of the partnership to avoid confusion and to ensure proper planning. This dynamic may shift during the life of a CMP and the decision around this should be guided by clear goals and objectives and effective monitoring and evaluation of the partnership and its attainment of clear targets.

Where CMPs are envisioned as an interim tool to build the management framework of the PA and the capacity of the PA authority, a clear timeline and measurable indicators should be outlined to ensure the public sector partner is fully equipped to resume full management control. The duration of this is dependent upon the local context and a number of factors such as conflict, political unrest, corruption, ease of doing business, and lack of funding mechanisms apart from donor funding. Establishing a realistic timeline for each particular PA is important when developing a CMP.

A clear timeline with indicators will also help ensure accountability by all parties. While the PA authority may opt for a long-term or even permanent CMP, they should consider that the long-term devolution of management responsibility to a partner may reduce the incentive for the public sector partner to engage in, or support, the development of conservation related financing initiatives that will foster economic sustainability.

In general, 15 to 20 years is recommended as a minimum. This provides adequate time to attract funding and investment, create SOPs, stabilize operations and transition management if this is the plan. Figure 3.4 is a hypothetical timeline for a CMP in a PA that is highly degraded.

X. Ensure Equitable Representation

Equitable representation on the governing board or committee of the CMP is paramount. No one party wishes to be or feel dominated by the other. A national PA is a public asset and therefore a sovereign matter with the state PA authority often reluctant to relinquish too much control. Nonetheless, the partner is bringing significant finances to the CMP, which requires a justifiable equitable stake, and in the case where the government opts for a delegated management model, often times the private partner has the casting vote. Nonetheless, every effort should be made to reach decisions by consensus, without relying on the casting vote.

The issue of representation, beyond the number of seats held by each party on the governance board, often manifests itself in the position of the board chair. One option is for the public partner to hold the position of chair within a minority of the board. The private partner holds the majority and therefore if consensus is not reached, holds the balance of power should a decision go to a vote. Another option is inclusion of an independent board chair, with expertise, influence, and a commitment to conservation, who hails from neither the public nor the private partner.

Where there is equal representation between the private and public partners:

o The board or committee should strive for consensus (with or without equal representation), whereby voting is avoided and matters are deliberated until a decision is mutually agreed and consensus is reached. This can certainly take time.

o The two parties jointly identify and nominate an independent person with relevant skills and expertise as chair, effectively acting as a neutral broker between the parties.

o Each party appoints a co-chair, which alternates at meetings. In the event the board fails to reach consensus on an issue, the two co-chairs should have the power to deliberate and decide the matter. If the matter still remains unresolved at this point, power of veto can be assigned to each party on particular matters, i.e., the public sector partner over matters pertaining to conservation policy or law enforcement (respecting the government’s ultimate authority over these matters) and the partner over matters pertaining to finance (recognizing that this party will be charged with primary financing responsibility). While not the norm in the corporate world, this option does meet the representation needs of the two parties. However, ideally in time, this arrangement can evolve as the working relationship, trust, and confidence between the parties embeds itself to the point where the parties agree to appoint one chairperson.

XI. Communicate the Partnership

There is a responsibility of both parties (public and private) to effectively communicate, internally and externally, about the establishment and operations of the CMP. This includes communication across the apparatus of the national government, so other ministries and civil service are fully informed and aware; regional/provincial authorities; and local/district authorities. It also encompasses local communities and traditional authorities.

Too often communication is lacking and misunderstandings and misperceptions arise as a result. This can manifest itself whereby other arms of government and the public at large do not realize that this is a partnership with government through its PA authority and erroneously conclude that the partner is the sole manager of the PA. This can create rumors, falsehoods, and negative political dynamics that undermine the actual partnership.

Effective and joint communication is an ongoing process through the life of the CMP and is not a one-off activity at inception. The process of communication is initiated first by the government authority when they start to consider CMPs and engage in a consultative process with key stakeholders. Once the CMP is in place, it should be a specific responsibility of the board to oversee and facilitate this communication ensuring that there is reasonable, regular communication to government ministries and authorities, local communities, and traditional leadership. The board can task management of this communication to a member of the senior management team and this should be guided by a communication strategy that is approved by both partners.

While seemingly superficial, appropriate branding of the partnership is essential and is one means to effectively highlight in particular the public sector involvement in the partnership. All communications materials, including correspondence, should include specific reference to the public and private sector entities involved, and a logo for the CMP should clearly include and illustrate each of the parties. For example, the Gonarezhou Conservation Trust logo indicates a partnership and other communications includes both partners (FZS) and the PA authority (ZPWMA).

Figure F.1 CMP Project Logo Example

I. Mitigate Risk

Minimizing inappropriate risk and liability is critical for a CMP and the individuals involved. If this is not achieved, one or either of the parties, its directors/trustees, and employees can be exposed to unacceptable levels of institutional and/or personal risk, which can result in legal and/or criminal proceedings. Such risk can also deter investment and donor funding. Moreover, it is also the fiduciary responsibility of a board to protect its partners, directors/trustees, and employees from unacceptable levels of public and personal liability.

This is especially important for the partner that is potentially exposed to a range of risks, which may not affect the public sector partner because of indemnification. Law enforcement is a case in point, where the private partner could be held liable for the injury or death of a staff member or a member of the public as a result of anti-poaching operations. This brings serious reputational risk.

Determining the appropriate corporate arrangement or structure for a CMP in light of this risk and liability is essential. Maximizing the protection of the partnership, and therefore its mission, will require consideration of corporate options that have not been commonly applied in the conservation sector; for example, a company limited by guarantee, a company limited by shares, or even a hybrid structure involving a trust and a company. In addition, a risk analysis should be completed by the partner as part of the partnership development process and reviewed and updated annually.

II. Unify Staffing

The ideal CMP should form and represent one single, unified structure of staffing instead of two parallel and separate staffing arrangements under each partner. This creates efficiencies, clear hierarchy and line management responsibility, streamlined communication, and builds a team spirit under uniform standards, procedures, and policies. Conversely, maintaining parallel, but separate staffing structures of the two parties in a bilateral CMP can result in division and at worst, resentment, and tension. If bilateral structures are in place in a CMP, the partners should work to mirror standards, procedures, and policies to the extent possible and clearly outline roles and responsibilities to avoid any confusion.

Establishing a unified staffing structure can be achieved through planned and coordinated secondment of staff by the parties to one of the partners or direct employment in the event of a dedicated SPV. It is essential that within this unified staff structure that no staff receives instructions from, or reports separately to either of the parties individually, but adheres to the agreed line management and reporting structure of the CMP.

III. Determine Management Leadership

Like most field-based programs, the caliber of executive leadership will very often be the deciding factor of success or failure of a CMP. The board should be responsible for appointing the senior executive management positions, including a chief executive officer (CEO) (in the event of a joint entity), either from nominated employees from each party under secondment or through direct recruitment. The manager is a pivotal appointment requiring an individual with skills in:

administration

financial management

fundraising

communications

enterprise development

PA management knowledge/experience

Best practice also recommends that the senior position responsible for law enforcement be seconded from the state PA authority. The senior leader must fully believe in the mission of the CMP and support the ultimate goal of building the capacity of the PA authority. They must have practical management experience in a PA and a sincere interest in and respect for differing opinions and cultures.

The resultant senior management team should be tasked with the appointment of all remaining staff (under a board-approved staff organizational chart for the PA) through the vetting and selection of proposed staff for secondment and where necessary direct recruitment. The senior management team, based upon approved human resource management procedures, shall have this responsibility to hire and appoint staff, and to dismiss. In the event of a dismissal of a seconded staff, the individual concerned would return to direct administration by his/her employer (one of the parties) and for further disciplinary action and/or redeployment elsewhere.

Without the ability to influence leadership in the PA, financial and technical support and bilateral partnerships can be hamstrung by a leader that lacks capacity and underperforms.

XV. Align Policies and Procedures

Senior management will be required to develop policies and procedures related to, amongst others, human resources, finance, and procurement. To ensure harmonization (and as an important feature for future succession), it is recommended that these policies and procedures, and subsequent manuals, be based on and adapted from government policies and procedures.

In an integrated CMP, both partners are responsible for following these policies and procedures. In a bilateral CMP, each partner may have their own policies and procedures; however, the partners should outline unified and guiding policies and procedures to ensure streamlining and consistency of operations.

XVI. Pre-plan Closure / Termination

In the event a CMP either fulfills its tenure or is dissolved by mutual consent prematurely or terminated due to a breach or non-performance of one partner, it is essential the parties pre-agree and understand at the outset a clear and thorough procedure for wind-up of the partnership. It is especially important to outline steps to deal, inter alia, with staff, assets, monies, liabilities, and ongoing third-party contracts and agreements. A lack of clarity over these matters can lead to discourse and disagreement between the parties at the time of closure or termination.

This procedure should address, for example, the following:

● What happens to staff directly employed (i.e., not seconded) by the partnership.

● How finances are reconciled and the process of dealing with balances held.

● How existing donor grants are managed.

● What happens to any financial liabilities at the time of closure; what and how assets are transferred and accordingly how asset insurance is addressed.

● What effect closure has on existing third-party contracts and agreements, such as contracts for tourism facilities and concessions.

Appendix P includes details of each of these aspects and how to incorporate them into a CMP contract.

XVII. Develop Work Plans Together

Developing the annual work plan together is efficient, draws on the expertise of both parties, creates a sense of ownership by both parties, and is a useful way of cross-pollinating technical skills into the public partner agency. Partners should develop an annual schedule that includes the review of the prior year’s achievements against the work plan and the development of the subsequent year’s work plan. This will also create awareness and transparency around budgets and create joint accountability. In situations where the private partner drives the annual work plan development and “hands” this to the public partner, this creates resentment and often leads to conflict. Likewise, when the PA authority develops the work plan and “hands” this to the private partner, there may be some management decisions required by the state that the private partner is not aware of and can lead to misinterpretation. A CMP is a partnership. Therefore, planning should be done together.

XVIII. Legitimize the Management Framework

The management and development of a PA by a CMP must be set within the legal framework of the host country. This will ensure that subsequent management and development subscribes to the prevailing policies, legislation, and regulations of the state.

A general management plan and related business plan for a PA provides a management framework. A GMP is established under PA and wildlife conservation law as the required and accepted instrument to frame the management and development of a PA and to implement relevant government policy. A GMP needs to be approved and ratified by the government, in some cases through ministerial endorsement. Once this is achieved, a GMP becomes in almost all jurisdictions a legal instrument.

Consequently, a CMP operating within the framework of a ratified GMP is implementing a legal instrument of government and is in turn implementing and subscribing to prevailing policy, legislative, and regulatory frameworks. This establishes legitimacy for the CMP beyond the endorsement and ratification of the CMP agreement.

XIX. Respect the Mandate of Law Enforcement

Law enforcement and security is a function of the state, and this is a dynamic that must be proactively respected within any CMP arrangement. Law enforcement undertaken by the private partner without the requisite legal authorization can pose serious liability for the private partner. This could result in criminal prosecution of staff of the private partner. It also risks serious misinterpretation and misperception around the private partner’s involvement with this function. It can be perceived as being solely conducted by the private partner, and accusations that the private partner is effectively operating a private militia can and have arisen. This is politically dangerous and can disrupt the partnership.

The law enforcement mandate of the government should be respected and remain vested with the state within a CMP. This can be achieved through the secondment of law enforcement staff from the PA authority to the SPV, thereby retaining the state as employer and their employees as law enforcement officers with the powers of: search, arrest, confiscation, etc.; the ability to carry more sophisticated (semi-automatic and automatic) firearms; and provide the necessary indemnity. However, they still report through the SPV, supporting a unified structure. Equally, the state can legally grant selected private partner employers involved with law enforcement with the necessary status, such as honorary rangers or police reservists, to conduct law enforcement with similar powers and protection. There are examples of CMPs that are in remote and insecure regions where the private partner has been delegated full oversight of law enforcement by the government, given the situation on the ground.

XX. Effectively Engage Stakeholder Communities

Local communities are almost always primary stakeholders and beneficiaries of a PA. Engagement and liaison with these communities cannot be separated from the PA. To do so would isolate and potentially alienate neighboring communities. Furthermore, primary engagement should not be conducted by a third party or be undertaken in parallel with the CMP. This can conflict with the strategy, objectives, and activities of the PA; cause confusion and tension; create inconsistency; and potentially duplicate effort.

It is, therefore, critical that the CMP be mandated to have primary responsibility to engage with identified neighboring communities over related conservation and livelihood activities; and to establish the necessary partnerships with local government and civil society organizations (if required) to promote and drive these programs. To this end, the CMP will need a dedicated community liaison or outreach department within its staffing structure.

In this regard, it is important that these “neighboring communities” be clearly identified and defined within a CMP arrangements and the geographical parameters of its engagement with these communities are agreed and communicated.

Partners should consider representation of the neighboring communities within their governance structure, either the Board of the CMP Governance body or the advisory committee, in instances where communities are key stakeholders. This was done, for example, in Niger for the CMP in Termit and Tin-Toumma National Nature Reserve and in the Republic of Congo for the CMP in Odzala-Kokoua NP. This will enhance communication between key stakeholders, garner support from the local community, and enable the CMP to take advantage of local knowledge. Local communities know the landscape, understand the threats, and know the dynamics taking place within the local areas. This would be an asset to the CMP.

XXI. Respect Transboundary Responsibility

When a PA is part of a TFCA, engagement with international neighbors and their PA authority is a sovereign matter; therefore, the designated state authority should continue to be the lead agency in international communication and coordination relating to the TFCA.

It is important that the private partner be kept abreast of TFCA matters so that it can contribute fully to the development and success of the TFCA. Accordingly, the state designated authority should copy relevant senior executive staff of the private partner into correspondence pertaining to the TFCA, and should invite these staff to attend meetings, workshops, and other events relating to the TFCA.

XXII. Build Towards Sustainability

Striving for financial sustainability of a PA is a key objective and motivation of a CMP. Reversing the norm of PAs as loss centers and creating the revenues to support improved conservation management are important drivers. Building the commercial basis towards financial sustainability will also help fuel the local rural economy and provide tax revenues to the government, creating incentives that can make a PA both socially and politically relevant. Co-investment by governments helps to leverage funding as it demonstrates a seriousness on the part of the government and helps to build sustainability.

In this regard, it is recommended that the CMP retain revenue generated from the PA to support its operating costs, and over time to reduce and ideally eliminate the need for donor financing over the long term. Such an arrangement will create a cost center and be highly attractive to investors and donors in the short to medium term when such finance will be necessary. Furthermore, recognizing that the private partner will bear the bulk of the responsibility for financial investment and support to the PA, this will create an important incentive for the private partner to build the commercial revenue side of the PA, as it will reduce the scale of operational shortfalls that it will be required to fund. While striving for sustainability and reducing the funding gap is critical, it is important to acknowledge that all PAs in Africa are subsidized and many, despite best efforts, will not attain financial sustainability because of remoteness, lack of enabling conditions, and inability to tap into commercial opportunities. Establishing clear and realistic financial targets is important to not raise unrealistic expectations.

XXIII. Drive Enterprise Development

Linked to the preceding principle, the CMP must be central to driving enterprise development within the PA and be given the requisite mandate to promote and develop such conservation enterprise. This includes being centrally involved in and/or managing the tendering, awarding, and contracting of enterprise and related concessions. Enterprise development is a specific skillset the PA authority should look for when selecting potential partners.

XXIV. Manage Surplus/Deficit

The partners in a CMP need a clear understanding at the outset of their obligations/rights in the event of operating surpluses and deficits. Determination of a projected surplus and shortfall needs to be framed within approved (by the board) and fixed annual budgets, so that expenditure is controlled and remains within reasonable, acceptable limits.

To create additional incentives for the state PA authority to support and facilitate the generation of commercial revenue streams for the PA, consideration should be given for the conditional release of annual operating income surpluses (essentially a form of “dividend”) to the PA authority. The following is recommended for the dividend:

Operating Risk Reserve — Distribution only after a reserve fund is established. A reserve fund should have enough funding to maintain the PA management operations for at least two years. When the reserve fund can be used should be defined in the CMP agreement and will include events such as disease (i.e., the COVID-19 pandemic) or conflict.

Stabilization Period — Distribution only after a fixed period (i.e., five years) following the inception of the CMP concerned. This acknowledges that the first five years (more or less depending on the local context) of a CMP will fundamentally be a development phase with significant capital development investment/expenditure and promotion/establishment of the enterprise base that will drive future revenue.

Distribution only when the annual surplus of operating income, which should be defined as arising purely from commercial revenues and should expressly exclude any donor income and after provisions are made for capital expenditures (CAPEX), for any given year exceeds (50 percent) of the previous year’s operating expenditure budget.

That the undistributed surplus (below the 50 percent threshold) is carried forward as operating reserves.

Equally, in preparation and in the event of operating deficits the public sector partner needs to agree from the outset its financial annual obligation. Ideally, this contribution for simplicity’s sake should be a fixed annual amount and targeted and ring-fenced for specific operating costs, such as payment of salaries of the state PA authority employees or seconded staff. Consequently, the private partner will be clear on its obligations to meet the resultant shortfall against an approved annual operating budget as well as its undertaking to fulfill capital development requirements.

Source: Adapted from Lindsey et al. 2020; Baghai et al. 2018; Conservation Capital 2017; consultation with CMP partners.

APPENDIX G. CMPs in Madagascar

Madagascar’s terrestrial and marine ecosystems are a global conservation priority with unparalleled endemism rates at species and higher taxonomic levels (Waeber et al. 2019). In 2003, Madagascar committed to tripling the extent of the country’s PA network, from under 2 million to 6 million hectares (covering approximately 10 percent of the national territory), under its Durban Vision, Vth World Parks Congress. By 2016, PA coverage in the country had quadrupled, from 1.7 million to 7.1 million hectares (Gardner et al. 2018; Rajaspera et al. 2011). To ensure the management of the PA estate, the government actively pursued management partnerships.

Madagascar’s PA network includes 147 nationally designated PAs, of which the ministry responsible for environment directly manages 15; Madagascar National Parks (MNP) (a parastatal organization) manages 43; and the rest are managed in partnership with national and international NGOs, and local communities (Gardner et al. 2018).

All non-MNP and ministry managed PAs have a legally recognized partner (referred to as a promoter), an international or Malagasy NGO (also universities, mining companies, and private individuals), and are generally governed through a shared governance arrangement incorporating regional authorities and local communities through community-based associations referred to as VOIs (Vondron'Olona Ifotany). The partners are considered as delegated managers of the PA on behalf of the government. These governance structures have evolved iteratively with the initial management plans at many sites outlining community management with partner NGOs or agencies playing a supporting role. In practice, due to lack of capacity and resources, partners are de facto co-managers, providing funds, technical capacity, and guidance (Waeber et al. 2019).

There are also formal management agreements in place with NGO partners. For example:

- Peregrine Fund Madagascar manages four PAs, including the Tsimembo Manambolomaty complex.

- WWF manages four protected areas.

- WCS has delegated management of Makira Natural Park, in the MaMaBay landscape/seascape northeast of Madagascar.

- Conservation International has delegated management of the Ankeniheny-Zahamena corridor and the Ambositra-Vondrozo and the Ambodivahibe Marine PA.

Approximately 12 percent of Madagascar’s GDP is supported by tourism and 80 percent of the visitors come to visit PAs. Despite the innovation around PA governance and collaborative management, Madagascar’s biological diversity is severely threatened by high rates of deforestation (driven by shifting cultivation, charcoal production, artisanal and industrial mining, bushmeat poaching, and over-harvesting of varied resources), resulting in significant species decline and threats of extinction (Gardner et al. 2018). Currently, there are over 1 million hectares of PAs (26 sites) of “paper parks” that are not managed (Razafison and Vyawahare 2020).

APPENDIX H. Contractual Parks in South Africa

South Africa’s apartheid policy introduced in 1958 affected every aspect of the lives of black South Africans—including where they could live and what they could own. In 1994, when Nelson Mandela was elected president, white people owned most of the land, while making up a minority of the population. That same year, the Land Reform Program was launched with an aim of developing equitable and sustainable mechanisms of land redistribution, and to rectify the centuries of discrimination against black South Africans. Along with the Land Reform Program, policies were passed to provide more opportunities for black South Africans to gain access and legal rights to land (Bosch, 2002/2003; Fitzgerald 2010). The Land Reform Program, still in effect today, has three primary aspects: land restitution/land claims: land tenure reform; and redistribution (Fitzgerald 2010).

At the same time, South Africa recognized the value of its PA system and sought creative mechanisms to secure and expand its PA network, while honoring the Land Reform Program. This resulted in a number of contractual parks, which are CMPs between communities, private landowners, and the national PA authority, SANParks. For example, the Kalahari Gemsbok NP (now Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park) is a CMP between the ‡Khomani San and Mier communities and SANParks. The ownership of land is shared between the communities and management is delegated to SANParks. A joint management board (JMB) comprising three SANParks officials and three to five representatives of both the San and the Mier communities oversees the management (Grossman and Holden n.d.).

The Makuleke Contractual Park (see Appendix D, Figure D.7) was created in 1999 and is viewed as a successful innovative solution that is a win-win for conservation and communities. In 1969, the Makuleke community was removed from its land, which was added to Kruger National Park. As part of South Africa’s land restitution process, the Makuleke regained title to their 24,000 hectares in 1998, and in 1999, the community created a contractual park by signing a 50-year delegated CMP agreement with SANParks (Fitzgerald 2010).

The land title is held by the Makuleke Community Property Association, which delegated management to SANParks. The Makuleke, in return, guarantee to use the land in a way that is compatible with the protection of wildlife and if the community wishes to sell, they have to offer it to the state first. A JMB has three representatives from each party and oversees the management decisions. The chair rotates annually and decision-making is by consensus (Bosch D. n.d.; Collins 2021).

The Makuleke have full rights to commercialize their land by entering partnerships with the private sector to build and operate game lodges that are consistent with the conservation management policies of the JMB. The Makuleke oversee tourism, while SANParks oversees conservation management (Collins 2021).

With the call by scientists and conservationists to increase global land and water conservation targets, CMPs present a practical and innovative model to ensure that communities are able to optimize the economic opportunities on their land if they lack the capacity and resources to do so on their own

APPENDIX I. Steps to Identify, Screen, Prepare, and Establish a CMP

Throughout the Toolkit there are links to useful references, checklists, and tools. This checklist includes the steps and some of the tools.

Table I.1 Steps to Identify, Screen, Prepare, and Establish a CMP

|

Process |

Chapter |

Section |

Step |

Tool |

Complete |

|

Identify and Screen CMPs |

4 |

4.1 |

Government decision to engage in a CMP |

Figure 4.1 Decision matrix tool |

Ö |

|

4.2 |

Legal review |

|

Ö |

||

|

4.3 |

Review agency goals and targets |

|

Ö |

||

|

|

Develop PA authority strategy |

|

Ö |

||

|

4.4 |

Screen and select potential PAs for CMPs |

Table 4.2 and 4.2 Sample tool for PA selection |

Ö |

||

|

|

Natural resource inventory |

|

Ö |

||

|

|

PA threat analysis |

Figure 4.6 Sample threat analysis |

Ö |

||

|

|

Performance audit |

|

Ö |

||

|

|

Risk analysis |

Box 5.1 Risk management |

|

||

|

4.5 |

Screen and select CMP models |

Figure 4.8 CMP model selection tool |

Ö |

||

|

4.6 |

Review regional plans |

|

Ö |

||

|

Prepare for Establishing a CMP |

5 |

5.1 |

Complete a feasibility study (when needed) |

|

Ö |

|

5.2 |

Determine the management partner selection process |

Table 5.1 Different mechanisms that might be used by a PA authority to establish a CMP |

Ö |

||

|

5.3 |

Pre-tendering stakeholder engagement |

Figure 5.3. Six-step guide to community engagement in CMPs |

Ö |

||

|

5.4 |

Formation of a proposal evaluation committee |

|

Ö |

||

|

5.5 |

Determine partner criteria |

Sample partner criteria |

Ö |

||

|

5.6 |

Prepare tendering materials |

Sample tendering materials Figure 5.5, and Appendices J and L |

Ö |

||

|

5.7 |

Tender process and selection of partner |

Figure 5.6 Tendering process steps and Resource Box 5.2 |

Ö |

||

|

A |

Expression of Interest |

Table 5.3 and Appendix M. Key components that should be included in an EOI |

Ö |

||

|

|

|

Appendix N. EOI evaluation form |

Ö |

||

|

B |

PEC reviews EOI against criteria, invites full proposals, support site visits |

Table 5.5 and Appendix O. Details to include in a full bid |

Ö |

||

|

C |

Partner selection process |

|

Ö |

||

|

Contract and Manage CMP |

5 |

5.8 |

Contract development |

Table 5.5 Standard headings in a CMP contract and Appendix P. Key aspects to include in a CMP contract |

Ö |

|

5.9 |

Contract management and monitoring |

|

Ö |

||

|

Environmental and Social Standards |

6 |

6.0 |

ESS |

Box 6.4 ESS and CMP Checklist |

Ö |

APPENDIX J. Sample Business Plans for CMP Bids and Planning

The CMP partner will submit a detailed business plan for PA management and community development as part of their bid. This will include operational costs, capital expenditures, and projected revenue. The business plan will guide the CMP and should be linked to an existing GMP if that is in place. If a GMP is not in place, the CMP partner will need to identify conservation targets and strategies to secure these targets. The inclusion of a business plan in the bid will enable the PA authority to assess familiarity with the PA, level of expertise in PA budget planning, and innovation around potential revenue sources. Below are resources on PA business plans and a sample business plan.

Resource Box J.1 Conservation Area Business Plans Tools

1. MedPAN Protected Area Business Planning Tool

An online Excel planning tool for PAs was developed by the Network of Marine Protected Areas managers in the Mediterranean (MedPAN), WWF, UN Environment Programme, the Regional Activity Centre for Specially Protected Areas, and the Mediterranean Action Plan Barcelona Convention with Vertigo Lab and updated in 2020 by Blue Seeds.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/18ytAEWMCjbELggoAAFq5TOMsRSqSGBjC/view

2. Protected Area Business Plan Database

The government of Seychelles, UN Development Programme, Global Environment Facility Protected Area Finance and Outer Islands projects developed a database containing over 40 examples of terrestrial and marine protected area business plans from around the world and guidelines for their development.

https://www.dropbox.com/sh/h5xb8vgl6tytvif/AABjU4MSEWqorDygFlNO0RZMa?dl=0

3. Financial Planning Spreadsheet for Activity-based Costing in Protected Areas

The Nature Conservancy; Conservation Gateway

An Excel planning tool for PAs.

https://www.conservationgateway.org/Files/Pages/financial-planning-spread.aspx

4. Guide for Preparing Simplified Business Plans for Protected Areas

Benjamin Landreau and Charlotte Karibuhoye, 2012

Sample Business Plan

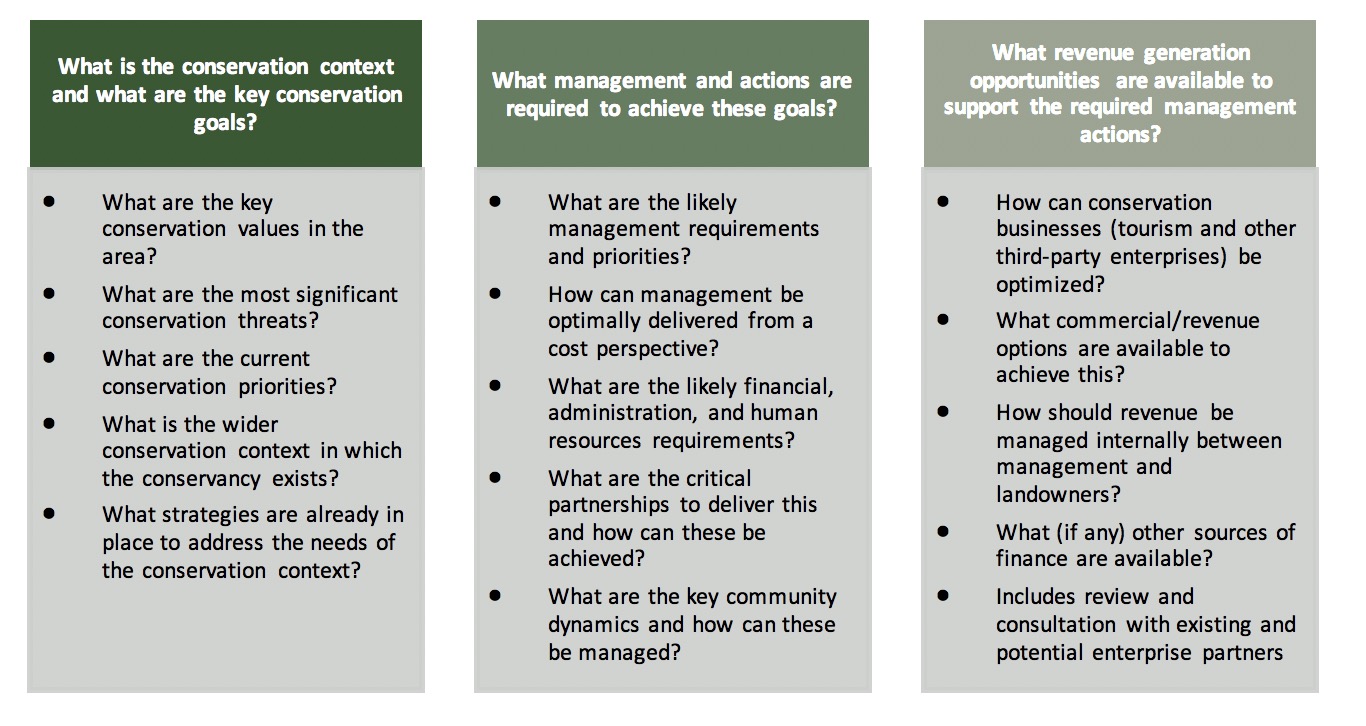

Conservation Capital developed a conservation area (term used interchangeably with PA) business planning (CABP) framework to assess the context and identify conservation needs and priorities of focal landscapes, consider commercial revenue development opportunities, and propose the institutional structuring required to optimize management performance and related revenue generation. Conservation Capital developed this methodology to help PA authorities and community and private landowners develop more financially efficient and sustainable approaches to managing PAs. This methodology provides a framework to address the operational cost side of management as well as potential revenue development, and assesses optimal management, commercial, and governance structures.

The CABP is driven by three primary considerations (see Figure J.1):

Needs of the underlying conservation context

Need for supporting conservancy management actions

Opportunity for commercial enterprise-based revenue opportunities

Figure J.1 Three Primary Considerations of a CABP

Source: Conservation Capital 2018.

A CABP provides a plan that includes the overall conservation outcomes that the relevant entity seeks to achieve, the strategies, activities, and resources needed to achieve them, and how to measure and share progress. Development of a CABP is an involving exercise that typically includes:

Status and situational assessment of the PA.

Review of existing plans, strategies, and other documents.

Defining desired outcomes and key indicators.

Defining the goals and strategies to achieve this, and specific actions.

Capacity assessment of the CA team’s experience and qualifications, and any additional capacity needed and how this could be addressed. This may include the role of partners critical to strategy execution.

Specific funding and other investment requirements.

Development of specific performance measures.

Part of the CABP is a detailed budget that includes four key sections:

Operational costs

Capital expenditure costs

Revenue

Combined cost and revenue

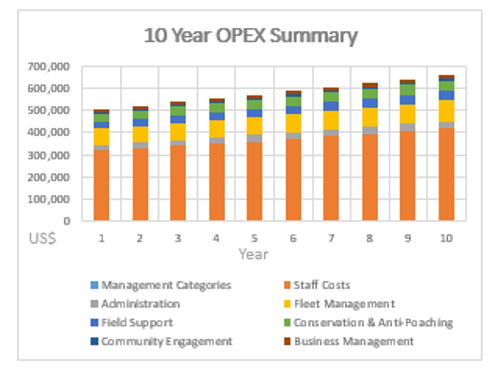

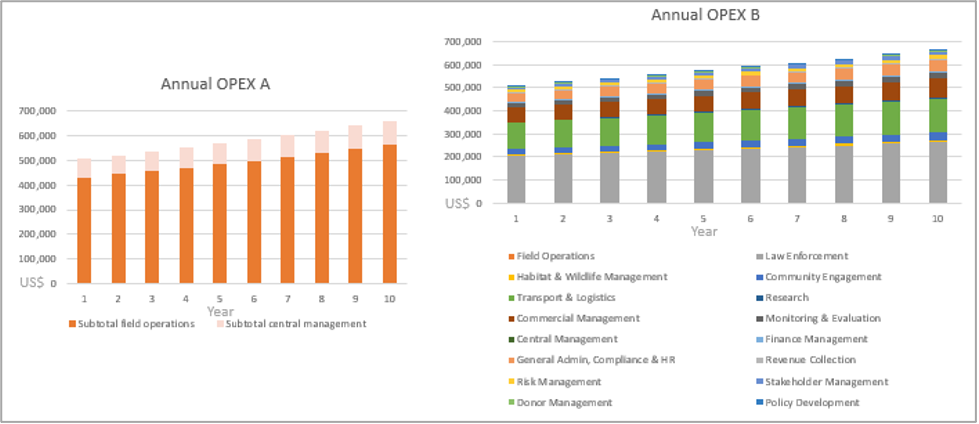

PA Operational costs (OPEX) are broken down in two ways—management categories (seven in the top section of Table J.1) and activity categories (field and central management, bottom section of Table J.1). There are detailed budgets for each management and activity category. Table J.1 is the summary.

Table J.1 10-year PA Operational Expenditures Investment Budget

Source: Conservation Capital 2018.

Figure J.2 10-Year Operational Expenditures Summary and Annual Operational Expenditures

Source: Conservation Capital 2018.

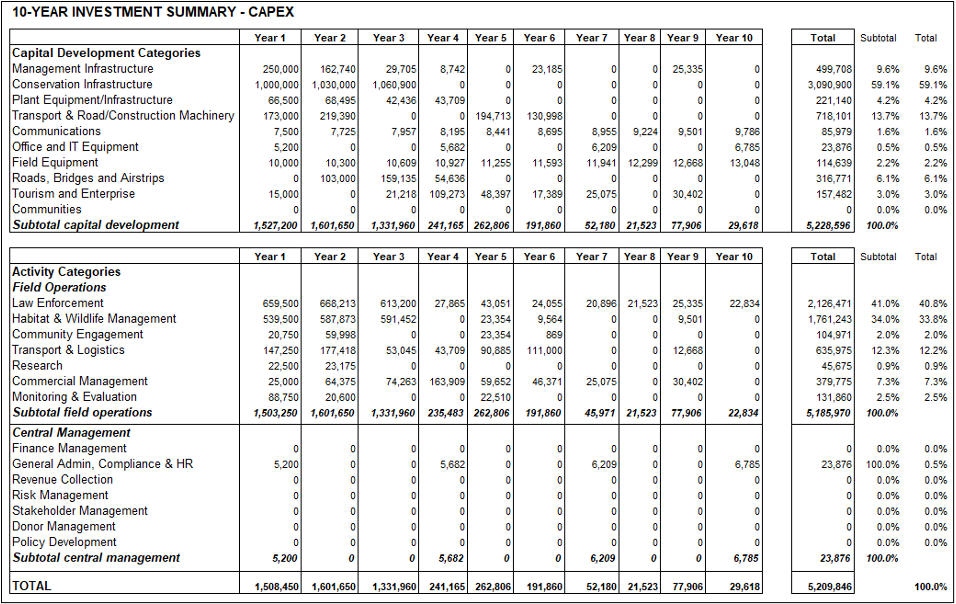

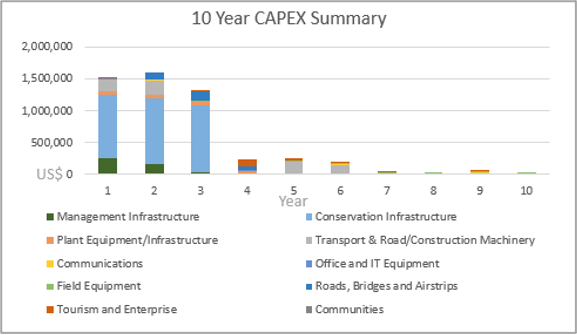

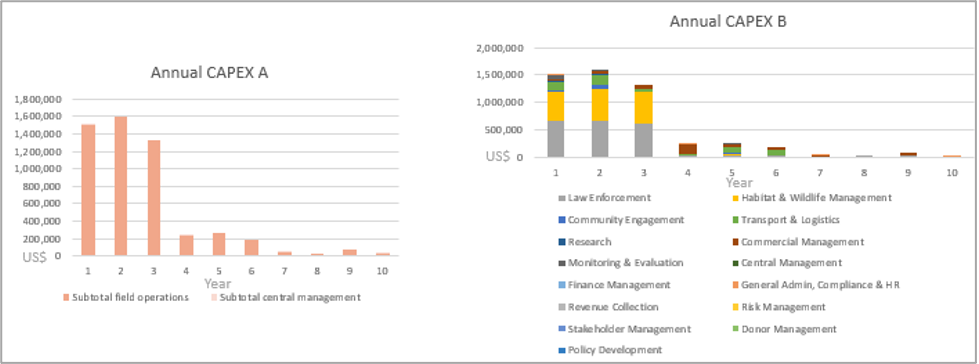

Capital Expenditure . Capital expenditure for a PA is budgeted along program areas, activity categories, and central management. Each program area and activity category has a detailed budget. Table J.2 is a summary of the 10-year CAPEX investment budget.

Table J.2 10-year PA Capital Expenditures Investment Budget

Source: Conservation Capital 2018.

Figure J.3 10-Year Capital Expenditures Summary and Annual Capital Expenditures

Source: Conservation Capital 2018.

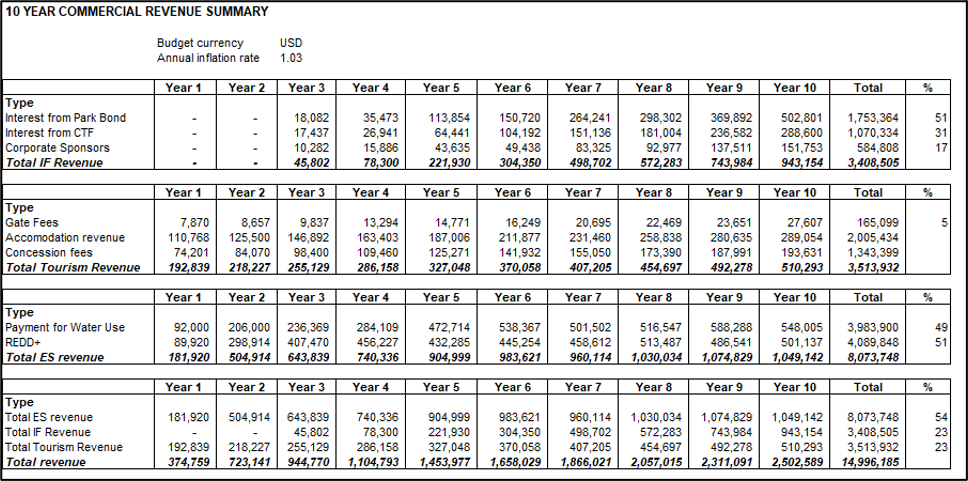

Revenue. Each revenue source has a detailed analysis that includes costs, projections, and trends. For example, the wildlife-based tourism fees include conservation fees, occupancy rates, and revenue retention. Table J.3 is a summary and includes three revenue sources: tourism, payment for ecosystem service (ES), and carbon credits through reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+). IF refers to innovative finance.

Table J.3 10-Year Commercial Revenue Summary

Source: Conservation Capital 2018.

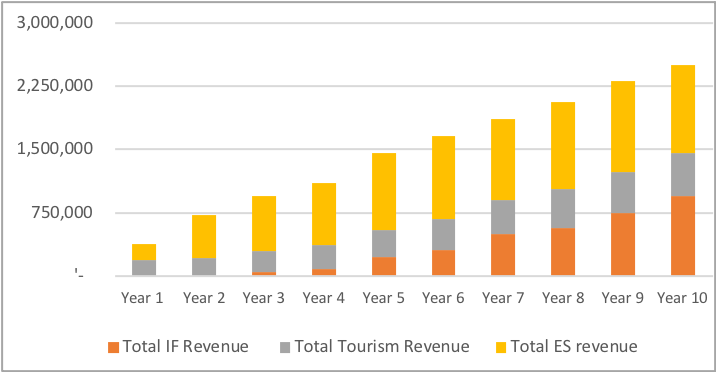

Figure J.4 combines all the revenue from Table J.3.

Figure J.4 Total Protected Area Revenue

Source: Conservation Capital 2018.

Combined cost and revenue over 10 years. The last component of the budget brings the costs and revenue together to determine the gap (see Figure J.6). The budget in Figure J.6 does not include donor funding. A donor funding and investment plan could be designed using the information from the CABP to fill the funding gap.

Figure J.5 10-Year PA Cost and Revenue Summary

Source : Conservation Capital 2018.

APPENDIX K. Sample Collaborative Management Tendering Information from Rwanda

Rwanda Development Board, July 12, 2018

In July 2018, RDB put out a tender notice to attract a partner for the management of Nyungwe NP. This was a public tendering process, which they advertised as per Rwanda law. In addition, they proactively sent letters to partners notifying them about the opportunity. This approach is recommended for any government considering tendering so that suitable partners are aware of the opportunity.

RDB also provided data on park visitors; park revenue; the park organizational structure and salary costs; the financial summary; and a description of the park infrastructure.

RDB requested the following information from bidders in its request for proposals.

I . Key elements of a concept proposal / expression of interest for the management and financing of the national parks identified above should include, but not be limited to some of the following elements:

- A detailed description of the potential financial, administrative, human resources, and management benefits that would be realized for the government and people of Rwanda if the RDB was to pursue an extended private-public partnership with the interested management company.

- A description of the anticipated benefits for conservation, enhanced tourism opportunities, and community engagement/development for each of the national parks of interest.

- A description of the two-to-three priority management actions for conservation, tourism, and community engagement/development that the management company would focus on first if a successful agreement was negotiated for the management of any or all of the other NPs.

- The proposed management structure and governance for the national park, with a description of how the management company would liaison and work with RDB for both policy development and management operations.

The anticipated investments required, including a preliminary costing / financial plan, a description of financial and/or economic viability, and value for money analysis.

The anticipated investments required, including a preliminary costing / financial plan, a description of financial and/or economic viability, and value for money analysis.

The projected revenues (revenue forecast), if any, that would accrue to the RDB as a result of management by the management company, including sources and any sensitivities (if exist).

A preliminary list and assessment of risks (if any), risk mitigations required, and management of risks.

The expectations of the RDB by the management company, if any, for ongoing support of operating funds and infrastructure investments within or adjacent to the national park.

Human resources management — the proposed approach the management company would take for current RDB employees at the national park, as well as for the provision of new employment opportunities for Rwandans in the future. Consideration for park ranger requirements (law enforcement personnel), employment opportunities for existing RDB park staff, and transition strategy for the RDB employees not deemed to be required by the management company should be included in the proposal.

The project preparedness of your management company (or organization) to take on this project in terms of capacity and skill assessment for project development, implementation, monitoring, and reporting.

Note : Given the success of the Akagera National Park governance and management structure, it is mandatory for the proponent to the proposal to use an Akagera National Park-like governance and management model, with the following minimum requirements:

Successful management company must incorporate as a company under the Rwanda Company Law (2009).

Financing of the company will be through a combination of park revenues, contributions from the government of Rwanda, contributions from the successful management company, and donor support.

The establishment of a board of directors for strategic and policy oversight of national park management for which members will be appointed by both the successful management company and the RDB.

Day-to-day management of the park shall be done by a park management unit under the leadership of a park manager, who is also the CEO of the management company.

Policy and management activities will be guided by a rolling five-year strategic business plan, annual activity plans, and annual budgets that will be approved by the board of directors

Law enforcement personnel (rangers) with the powers of peace officer shall be seconded/transferred from RDB.

II . Requirements of the Potential Partner / Management Company

In addition to the elements of the proposal outlined above, the potential partner/management company will meet and clearly demonstrate (describe) in the expression of interest proposal, that they meet the following interests, knowledge, and abilities/experience factors.

Interest:

Have a genuine interest in the development and advancement of Rwanda as a nation, for which conservation-based tourism and community economic development through the protection of its natural biodiversity and ecosystems is a priority.

Knowledge:

Of ecosystem conservation, restoration, management planning, techniques, and practices.

Of sustainable tourism principles, practices, and techniques, including marketing and promotions of park and park experiences.

Of community engagement and economic development principles and practices, within an African conservation context.

Of financial and human resources principals, practices, and techniques.

Experience:

Must have a minimum of 10 years of experience in contributing to and/or supporting the management of parks and protected areas, either all for countries within Africa or a combination of countries outside Africa and countries within Africa — mandatory criteria.

In successfully managing multiple national parks or protected areas within the African continent ( Successful management of multiple national parks / protected areas — this criteria is not mandatory, but will be used to rate the proposal, with preference / score given to those management companies who can clearly demonstrate management of up to five national parks or protected areas. ) with a full range of conservation, protection, sustainable tourism, and community engagement/economic development responsibilities, including:

In the implementation of ecosystem conservation, restoration, and management of protected areas/natural areas.

In the development and implementation of tourism program development and delivery including: meaningful visitor experiences; promotions and marketing; and working with tourism industry partners.

Developing and managing a healthy, productive workforce.

The development and delivery of park visitor and community education outreach programs to build national park/protected areas supporters and constituents.

Working with government and NGOs in the management of conservation-based lands and/or programs.

Financial management, including private and public sector fundraising to support management programs.

Letter(s) of recommendation:

One or more letters of recommendation from the governments and/or organizations for which the proponent has successfully managed protected areas outlined above

III. Proposed Duration of Services

The RDB is willing to consider a park management agreement for up to twenty (20) years, renewable and to commence after the signing of an agreement between the successful protected areas management company and the RDB. The management company must include in its proposal, the duration of time for an agreement, should they be successful.

IV. Submission and Review Process:

The submission and review process for this expression of interest will be in two steps:

Step 1. Preliminary management proposal, including:

Development and submission of a preliminary proposal by the potential management companies on the basis of preliminary criteria provided by RDB.

A presentation of the preliminary proposal to RDB by the potential management company.

A more detailed review and evaluation by RDB of the management company preliminary proposal and a decision as to whether to request a more detailed proposal, or not.

Communicate results of the RDB decision(s) for Step 1 to the potential management company (ies) who have submitted preliminary proposals.

Step 2. A detailed park management proposal, including:

Invitations to develop and submit a detailed proposal on the basis of preliminary criteria provided by RDB (criteria yet to be developed).

Development of a detailed proposal by the potential management companies.

Presentation of proposal to RDB by potential management company.

A more detailed review and evaluation by RDB of the management company’s proposal and decision by RDB.

Communicate results of decisions by RDB to potential management companies.

● More detailed contract / PPP Agreement negotiations with the preferred management company selected by RDB.

V . Submission Requirements for Expressions of Interest/Proposal

Interested management companies and organizations who meet the above noted requirements are invited to submit their Proposal, which will include the following information:

Confirmation of interest to be considered for the management and financing of Nyungwe National Park.

General information about the management company / organization that is submitting the proposal, including: main business; country (ies) of establishment, operations and duration of conservation-based business activities.

Information related to the key information elements outlined above.

Information related to how they meet the interest, knowledge, abilities, and experience elements of request for proposals, as outlined above.

An indication of the length of time the management company would consider managing the national park should they be successful, as outlined above.

● Deadline

● Address for submission

● Information Provided by RDB to interested partners

APPENDIX L. Sample Promotional Materials for CMPs from Uganda

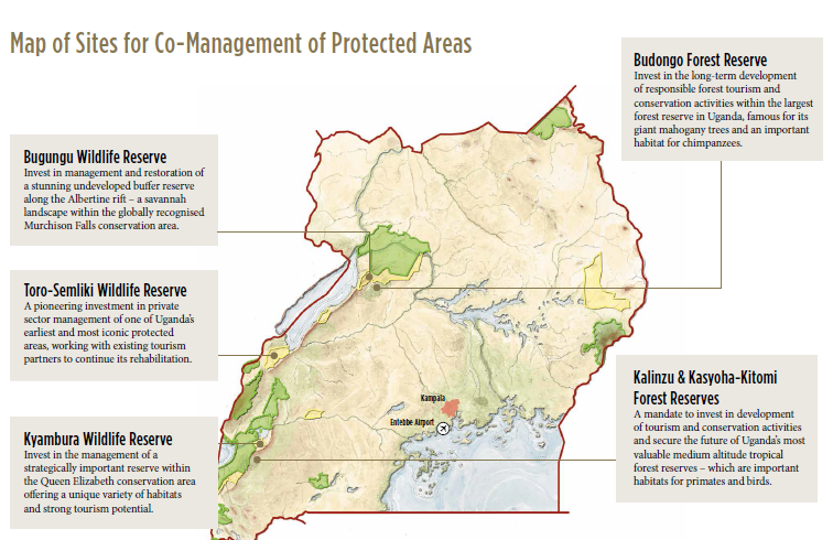

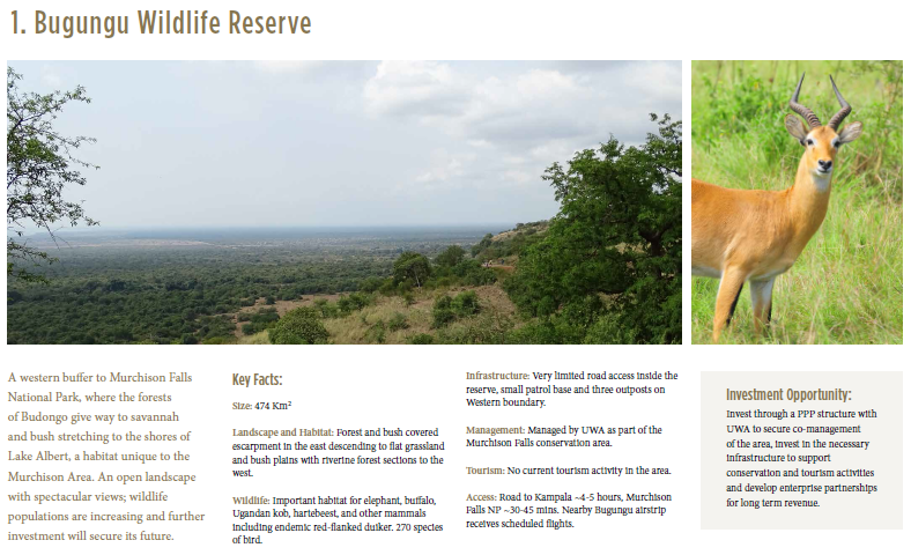

When a CA is embarking on a CMP tendering process, it will need prospectus documents that describe the CMP opportunity and the focal PA. In addition to the sample provided in Section 5.6 from Mozambique, below is from a 2017 conservation and tourism investment forum in Uganda where CMP and tourism opportunities were promoted to potential investors, donors, and partners.

Figure L.1 Map of Potential CMP Sites in Uganda

Figure L.2 Description of CMP Opportunity in Bugungu Wildlife Reserve

Source: The Giants Club and the Government of Uganda 2017.

APPENDIX M. Information for an Expression of Interest

The following information should be included in an EOI for engagement in a CMP.

a. Potential Partner Identify: The bidding organization’s legal identity, structure, and registration information.

b. Key People: Summary biographies of the key people behind the bidding organization.

c. Experience: Summary evidence of 10+ years of relevant engagement in biodiversity conservation, protected area management, and experience in the relevant country.

d. International Best Practice: Evidence of connections with and exposure to international best practice (in Africa and where possible beyond) in the field of conservation area management.

e. Experience in Target PA: A summary of prior operating experience in the targeted PA or its environs.

f. Technical Capacity: Specific evidence of prior successes and positive impact with:

Protected Area Management : conservation development and management of PAs.

Local Community : proactive community engagement and integration and related economic development.

Revenue : progressive nature-based revenue development in protected area contexts — with a particular focus on tourism development and marketing.

Fundraising : donor fundraising, management, and networks.

Conservation Financing : knowledge and application of other innovative conservation financing mechanisms beyond mainstream donor fundraising.

Start-Ups : experience with start-ups — new project development.

Technology : progressive use of technology in conservation development.

Business and PA Planning : experience with professional and realistic business plans and PA management plans.

Environmental and Social Standards ; familiarity and experience with ESS and a plan to comply with ESS (see Chapter 6).

Project Management : exceptional organizational skills and management of complex and dynamic projects.

- Key Priorities : A summary of the anticipated priority management actions for the PA with specific reference to conservation, local community and economic development impacts.

- Alignment with PA authority: The partner’s understanding of the PA authority’s vision and goals and how the CMP will support this vision and help the government achieve key national and international targets and objectives.

- Conflict of Interest : Certification that the partner does not have any conflict of interest and/or is declaring a conflict of interest, which they believe is manageable.

- References : Letters of recommendation from at least two credible independent sources relevant to the interested private sector party’s CMP proposal.

APPENDIX N. Sample Expression of Interest Evaluation Form

Once an EOI is submitted, the PEC can use the sample evaluation form to rank the submissions and determine which potential partners should submit a full bid.

Table N.1 Expression of Interest Evaluation Form

|

Expression of Interest Evaluation Form |

||

|

Name of Bidder: CMP Partner Bidder |

||

|

Name of Evaluator: Member of the PEC |

||

|

Date of Evaluation: Day / Month / Year |

||

|

Category |

Key Component |

Yes =1 / No = 0 |

|

Overall Submission |

|

|

|

|

Submission on time |

1 |

|

|

Well-written |

1 |

|

|

Professional |

1 |

|

|

Includes all requirements |

1 |

|

|

Partner identity |

1 |

|

|

Lack of conflict of interest |

1 |

|

|

References |

1 |

|

Subtotal |

(Highest Score Possible = 7) |

7 |

|

Experience |

|

Qualification High=2 / Med=1 / Low=0 |

|

|

Key people’s biographies and CVs |

1 |

|

|

Experience |

1 |

|

|

International best practice |

1 |

|

|

Experience in target PA |

0 |

|

Technical Capacity |

|

|

|

|

PA management |

1 |

|

|

Local community |

1 |

|

|

Revenue |

1 |

|

|

Fundraising |

1 |

|

|

Conservation finance |

1 |

|

|

Start-ups |

1 |

|

|

Technology |

1 |

|

|

Business and PA planning |

2 |

|

|

Environmental and social standards |

2 |

|

|

Project management |

0 |

|

Project Description |

|

|

|

|

Key priorities |

2 |

|

|

Alignment with PA Authority |

0 |

|

Subtotal |

(Highest Score Possible = 32) |

12 |

|

Total |

(Highest Score Possible = 39) |

19 |

|

Evaluator Signature: |

||

APPENDIX O. Information for a Full CMP Bid

After EOIs are submitted, the PEC will review solicit full bids, which should include:

Corporate and Governance

a. Proposed Corporate Structure

Description of the proposed corporate structure.