Protected areas are the cornerstones of biodiversity conservation and a valuable buffer against the impacts of climate change. However, the global PA estate has been largely under-valued by traditional economic and financial systems that do not incorporate the vast service provisions provided by PAs. This chapter outlines the value of protected areas, the financial gap in biodiversity funding, and the resultant decline in biodiversity. It outlines the target audience for the Toolkit, the methodology, and defines key terms.

1.1 - Introduction

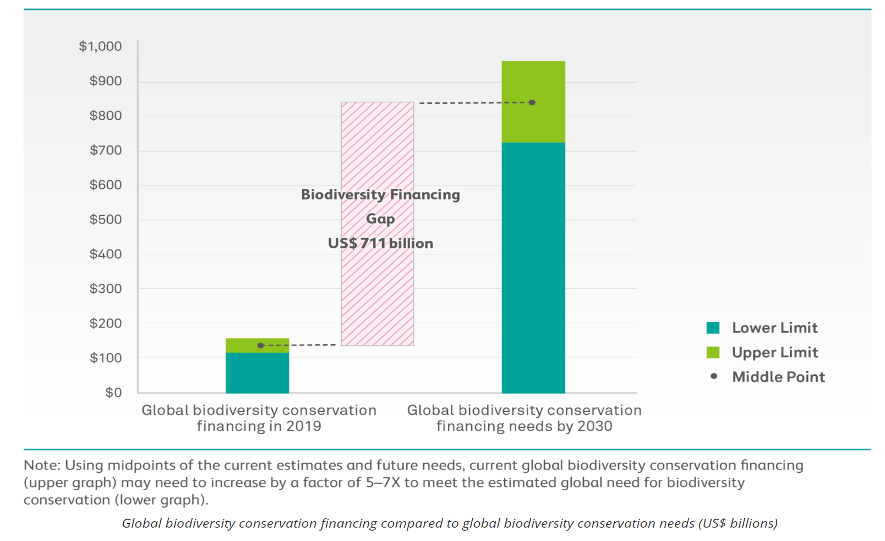

Despite the recognized role of PAs and the systemic risks they face, a report by the Paulson Institute found that as of 2019, a biodiversity financing gap exists of between $598 billion and $824 billion per year (Deutz et al. 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has widened the funding gap by crowding out investment in biodiversity and PAs in lieu of financing for other sectors at a time when traditional revenue streams for conservation, such as nature-based tourism (NBT), have decreased or disappeared. The fiscal and monetary stimulus policies adopted by governments to keep economies afloat will further reduce funding available for environmental conservation (Lindsey et al 2020). In addition, countries are taking on more debt to address the pressing health and economic impacts of COVID-19, which will further strain already limited resources.

New and innovative solutions and partnerships are needed to attract funding and investment, prevent the loss of biodiversity, and enhance ecological and social resiliency. Developing countries require substantial additional resources and solutions to effectively manage their PAs. Engaging the private sector and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to channel additional financial and technical resources is critical for the long-term sustainability of PAs and to support the ecosystem services and climate change benefits they provide.

Collaborative management partnerships (CMPs) are being deployed globally to enhance PA management effectiveness and catalyze green development, and they are particularly relevant in Africa. A CMP refers to when a PA authority (government, private, or community) enters a contract with a partner (private or NGO) for the management of a PA (Baghai 2018). There are three kinds of CMPs: financial and technical support, co-management, and delegated management. Approximately 11.5 percent of Africa’s PA estate is covered by co-management and delegated CMPs.

CMPs are a type of public-private partnership (PPP). The World Bank has produced numerous toolkits and reference materials that document experiences of different countries and sectors in creating and implementing PPPs. Given the severe gap in PA funding and the role of CMPs in conservation, this Collaborative Management Partnerships for Protected Area Conservation and Development Toolkit (CMP Toolkit) builds on the World Bank’s PPP efforts and is tailored for the PA sector. In 2018, PA experts published a paper in Biological Conservation on CMPs in Africa as a means of enhancing PA management and attracting investment (Baghai et al. 2018). One recommendation, given the vast area over which CMPs are deployed and the potential they confer for catalyzing resources for conservation, was for the development of best practice guidelines (Lindsey et al. 2021).

This CMP Toolkit aims to assess CMP models, serve as a reference guide for governments and implementing partners considering CMPs, and raise awareness of CMP experiences in Africa to highlight benefits, challenges, and lessons learned. The Toolkit will be enhanced over time with additional insights and technical resources as more governments, communities, private landowners, private sector, and NGO partners increase collaboration and enter into long-term contracts to increase the value of public environmental assets that deliver local and global environmental, social, and economic benefits.

1.2 - Value of Biodiversity and Role of Protected Areas

Biodiversity and ecosystem services are the foundation of human well-being. They underpin our economies, livelihoods, and health, and yet, they are grossly under-valued and not captured in traditional financial models (Lindsey et al 2021). Global biodiversity is under severe threat with critical implications for human well-being. The accelerating loss of biodiversity and the associated impacts are expected to further weaken economies, exacerbate global food insecurity, and compromise the welfare of people (World Bank Group 2020c). The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report rates biodiversity loss as the second most impactful and third most likely risk for the next decade (World Economic Forum 2020).

Well-funded, socially inclusive, and competently managed PAs are the most effective tools to conserve biodiversity (Sanderson 2018). Their effective management and sustainability is essential to biodiversity conservation, climate mitigation, and delivery of ecosystem services depended on by populations and economies (Lindsey et al. 2018).

Biodiversity provides us with food, water, and shelter; regulates our climate and diseases; maintains nutrient cycles and oxygen production; and provides us with spiritual fulfillment and opportunities for recreation and recuperation, which can enhance human health and well-being (Dasgupta 2021). Most of nature’s contributions to people are not fully replaceable, and some are irreplaceable. Protected areas are the cornerstones of biodiversity conservation and a valuable buffer against the impacts of climate change (World Bank 2008). They sustain ecosystem services, natural processes, and key species, and drive economic growth. However, PAs are at risk.

The global PA estate has been largely under-valued by traditional economic and financial systems that do not incorporate the vast service provisions provided by PAs. The depletion of the globe’s natural capital — including natural assets such as forests, water, fish stocks, minerals, biodiversity, and land — poses a significant challenge to achieving poverty reduction and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The heightened awareness around the value of natural capital and the central role PAs play in securing ecosystem services and mitigating the impacts of climate change (Dinerstein 2019) has resulted in various natural capital accounting systems that aim to value these natural assets. The Changing Wealth of Nations report provides 20 years of wealth accounting data for 141 countries and incorporates natural capital as a key factor in determining the wealth of countries (Lange et al. 2018).

Africa supports a quarter of the globe’s biological diversity, nearly 2,000 key biodiversity areas, the second-largest tropical forest in the world, and the most intact assemblages of large mammals on earth (Lindsey et al. 2020). Africa’s biodiversity has been conserved through an extensive network of PAs, including 8,601 terrestrial and marine PAs, covering 14 percent of the continent’s land area and 12 percent of the marine area. These PAs support rare, threatened, and endangered species, vast and diverse ecosystems, and ecosystem services that support human well-being and Africa’s economies.

Africa’s tourism economy, which is driven by its PAs and associated wildlife, contributed 10.3 percent to the continent’s gross domestic product (GDP) and generated $61 billion in 2019. That same year, tourism supported 24.7 million jobs, which accounted for 6.9 percent of the total employment on the continent. While the COVID-19 pandemic has had a catastrophic impact on the travel and tourism industry and its associated revenue and employment benefits (Lindsey et al. 2020), the tourism market is expected to return and growth in certain parts of the sector is projected to continue.

Africa’s PA estate contributes to the economy in many other ways beyond tourism. In Ethiopia, the economic value of ecosystem services in its PAs is estimated to be at least $325 billion per year, and with improved management, this value could double (Van Zyl 2015). In southern Kenya, the Chyulu Hills National Park (NP) and the broader Tsavo conservation landscape provide vital watershed services for the surrounding area and Mombasa, Kenya’s second-largest city. The protection of this forest landscape results in 600,000 tons of avoided carbon emissions per year, valued at almost $5 million per annum (assuming $8 per ton of carbon).

The Nature Conservancy’s Water Fund in Cape Town, South Africa, found that “green” ecological infrastructure restoration (i.e., the protection of forest, reforestation, and removal of invasive species) costs five to 12 times less than “grey” infrastructure (i.e., desalinizing ocean water, drilling for groundwater, building dams). It also found that green infrastructure could reclaim more water per year for Cape Town, a city of four million people that has suffered enormous challenges from lack of water.

Over the past three decades, PAs have increased across Africa. In May 2020, the Seychelles created 13 new marine PAs protecting 400,000 square kilometers (km2), an area twice the size of Britain (Vyawahare 2020). The expansion of PAs in Africa is due to the recognition by governments of the economic and ecological value of PAs, as well as obligations under global treaties such as the Convention for Biological Diversity (CBD). In 2010, the CBD’s Aichi Target 11 established PA targets for the ensuing decade:

“By 2020, at least 17 percent of terrestrial and inland water, and 10 percent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative, and well‐connected systems of protected areas and other effective area‐based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes.”

According to the CBD, approximately 23 percent of the countries either met or exceeded Aichi Target 11 by 2020, while 56 percent did not report on targets, 16 percent fell short, four percent made no progress, and one percent is unknown. The trend in PA expansion is anticipated to continue. There are calls from scientists and NGOs to increase the post-2020 CBD targets from 17 percent to 30 percent by 2030, and more than 50 governments have already committed. Scientists argue that formal protection of 30 percent of the Earth is required to prevent the average global temperature from rising above 1.5º C, and that securing an additional 20 percent of the planet is needed for climate stabilization by 2050 (Dinerstein et al. 2019).

1.3 - Protected Area Funding Gap

Despite the recognition of the value of biodiversity and the role PAs play in securing the world’s natural capital and ecosystem services, a massive funding gap exists for PA management and biodiversity conservation. Assessing the requirements for maintaining biodiversity and comparing this with existing budgets, the Paulson Institute found that the global biodiversity financing gap is from $598 billion to $824 billion per year (Deutz et al. 2020) (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 - Global Biodiversity Gap

Source: Deutz et al. 2020.

As threats to biodiversity continue to escalate, the cost of protecting and restoring these vital natural assets also will increase. The Global Futures project estimates that under a business-as-usual scenario, the costs of biodiversity loss in some countries could be as high as four percent of their GDP per year by 2050 (Roxburgh et al. 2020).

The dearth of biodiversity funding in Africa is no different. In 2018, researchers assessed 282 state-owned PAs in Africa with lions and found 94 percent were funded insufficiently, with available funding satisfying only 10-20 percent of PA requirements on average. The study concluded that more than $1 billion is needed annually to secure Africa’s PAs with lions. Overall, sufficient long-term financial resources are required for Africa’s PA estate to be managed effectively (Lindsey et al. 2018).

The PA funding gap varies across the continent. For example, using existing donor and state funding, the estimated budget gap for effective PA management for lions in Angola is 98 percent, while in Uganda the gap is estimated to be 67 percent (Lindsey et al. 2018). While the exact scale of the financial gap might be debated, it is widely accepted that PAs need a reliable source of funding to maintain their management operations, meet conservation targets, and provide quality visitor experiences where appropriate, and that the current funding available is wholly inadequate (IUCN ESARO 2017).

Africa’s PAs are financed from three main sources: budget allocation from national governments, revenue from tourism and other user rights, and donor funding. PA funding is not equally allocated across the PA estate, with some PAs receiving more resources than others. In some cases, a portion of revenue is allocated to the PA authorities’ headquarters (IUCN ESARO 2020a). Most, if not all, PA authorities receive some level of national government support, with the funding relatively unpredictable and often inadequate as governments have competing needs from other sectors such as infrastructure, health care, education, and food security (IUCN ESARO 2020a).

In East and Southern Africa, many of the PA authorities rely on revenue generated from tourism. In 2017, tourism revenue comprised 50 percent of the Kenya Wildlife Service’s (KWS) annual budget. In 2019, tourism revenue supplied 80 percent of the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority’s (ZPWMA) budget, while the South African National Parks (SANParks) budget also received 80 percent of its funding from tourism in 2018-19 (IUCN ESARO 2020a). External donors, including private and institutional donors, support approximately 32 percent of the current PA funding in Africa, reaching 70-90 percent in some countries. PA management requires long-term and reliable funding, which makes reliance on sometimes unpredictable donor funding a management challenge for PA authorities (IUCN ESARO 2020a).

The COVID-19 pandemic has strained all three sources of PA revenue, dramatically exacerbating the PA funding gap and putting biodiversity at greater risk (Lindsey et al. 2020). National governments have cut, and will continue to cut, conservation budgets to address COVID-related issues. Across Africa, there has been a 60-90 percent decline in tourism-related revenue for PA management due to the travel lockdowns. Approximately 90 percent of African tour operators have experienced a 75 percent or greater decline in bookings (Lindsey et al. 2020). In 2020, the contribution of tourism to Africa’s GDP decreased by 49 percent ($83 billion) and jobs decreased by 29 percent (7.2 million). While donor funding has increased during the COVID crisis to address the emergency period, the cost of maintaining biodiversity continues to escalate because of increasing pressure, and there are concerns about the ability to maintain funding levels. Simultaneously, there is a concerted effort by scientists and conservationists (see Section 1.2) to increase national PA targets post-2020 to up to 30 percent, which will require additional resources. More funding and innovative financial solutions are needed to ensure the effective management of the existing and expanding PAs.

1.4 - Management Effectiveness

The lack of adequate PA management finance (see Section 1.3) is resulting in the underperformance of Africa’s PA network, putting species, ecosystems, and the network itself at risk. Protected areas management effectiveness (PAME) relates to the extent to which management is effective at conserving values and achieving goals and objectives, such as protecting biodiversity (IUCN ESARO 2017).

For PAs to fulfill their obligations, they need adequate resources and capacity. Otherwise, they become non-performing PAs, commonly referred to as “paper parks.” The CBD’s Aichi Target 11 recognizes that increases in PA coverage alone will not halt the loss of biodiversity, highlighting the need for effective management.

In 2020, researchers assessed budgets, management, and threats for 516 PAs and community conservation areas with lions in savannah Africa to determine conservation performance related to biodiversity outcomes, which they compiled into a Conservation Area Performance Index (CAPI). They found that 82 percent of the sampled area was in a state of failure or deterioration, with only 10 percent in a state of success or recovery. A large proportion of the succeeding or recovering PAs have CMPs. The CAPI values varied by region and were lowest in central and West Africa, followed by East and Southern Africa. They also found that the CAPI differed by management regime, including state, private, and community conservation areas (Robson 2021).

While a number of tools are available for PA managers to measure PAME, only 26 percent of Africa’s PAs have completed PAME assessments due to a lack of capacity, meaning there is little understanding of actual PA performance by PA managers. Many assessments in East and Southern Africa were completed only one time or with a different tool in the subsequent year, which does not help a PA manager track progress over time — the very purpose of monitoring management effectiveness.

The CBD Conference of Party 10 Decision X/31 calls for Parties to “… expand and institutionalize management effectiveness assessments to work towards assessing 60 percent of the total area of PAs by 2015 … and report the results into the global database on management effectiveness” (CBD 2010).

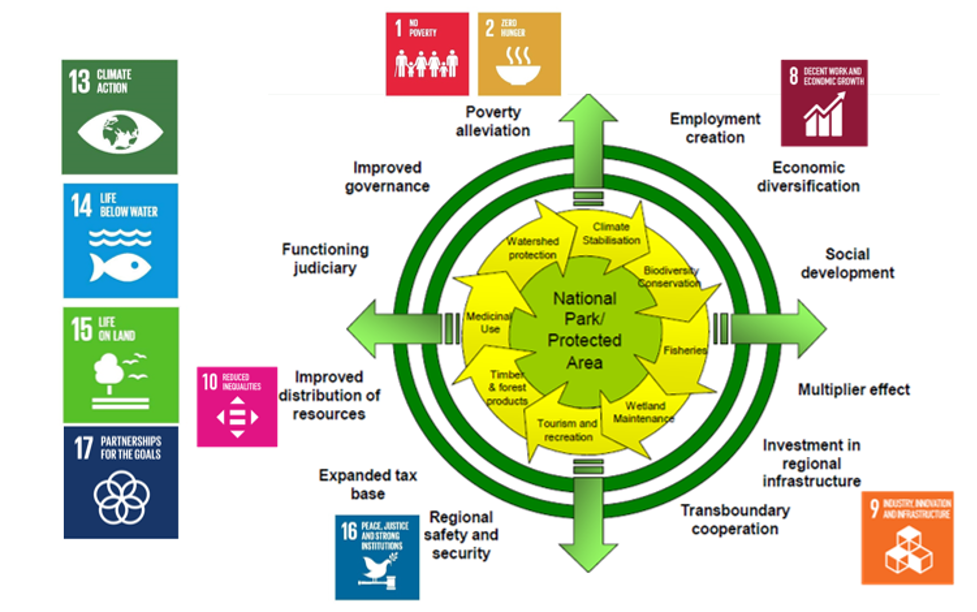

The effective management of PAs can help governments achieve their CBD targets as well as other national and global commitments, such as SDGs. For example, a well-managed PA can enable a government to meet SDG targets 1, 2, 8, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16, and 17 as depicted in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 - Protected Areas and the SDGs

Source: Adapted from African Parks.

Effectively managed PAs can help governments achieve national targets. In South Africa, for example, the government established goals under its Green Economy Plan. Likewise, Kenya’s Vision 2030 and Rwanda’s Green Growth and Climate Resilience National Strategy for Climate Change and Low Carbon Development outline targets that CMPs can help governments achieve.

1.5 - Biodiversity at Risk

Ineffective PA management is exacerbating key threats driving the overall decline in biological diversity in Africa, such as illegal wildlife trade (IWT), poaching, habitat conversion, illegal logging, unregulated mining, grazing, unsustainable agriculture and settlement, climate change, and the spread of invasive species. These threats pose a significant risk to Africa’s wildlife, clean water and air, productive soils, fish stocks, and other key environmental services.

The Congo Basin, the world’s second-largest tropical forest, spans six countries in Central Africa and is globally significant for climate mitigation. This expansive tropical forest absorbs approximately 1.2 billion tons of carbon dioxide each year, and its trees store a third more carbon over the same area of land than those of the Amazon (Yeung 2021). According to Global Forest Watch, an initiative of the World Resources Institute, primary rainforest loss in the Congo Basin Forest more than doubled from 2002 to 2019. In 2019 alone, 590,000 hectares were lost — an area more than half the size of Jamaica (Yeung 2021).

Over the last 25 years, Africa’s lion population has declined by 50 percent (Stolton and Dudley 2019). Approximately 56 percent of the lion’s range falls in PAs (Lindsey et al. 2018), a proportion that is likely to grow rapidly as wildlife outside PAs disappears. All of Africa’s great ape species are rare, threatened, or endangered, with trends indicating a continued decline for all except the mountain gorilla. From 2007 to 2014, Africa’s elephant population declined by 30 percent, and from 1980 to 2020, giraffes declined by 30 percent. This unprecedented decline of key species is emblematic of the overall biodiversity and ecosystem service loss in Africa.

These trends in Africa mirror global biodiversity loss patterns. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) report of 2019, the most comprehensive of its kind, found that nature is declining globally at rates unprecedented in human history and the rate of species extinctions is accelerating, with grave impacts likely on people around the world. A WWF (2020) report revealed an average decline of 68 percent in vertebrate species numbers between 1970 and 2016. The IPBES report also found that the current global response is insufficient, and that transformative change is needed to restore and protect nature (IPBES 2019). These trends in biodiversity loss are exacerbated by the impact of climate change (WBG 2020c).

Recognizing the unparalleled decline in biodiversity and intensifying threats alongside the severe limitations in PA funding, many African governments are partnering with NGOs and the private sector in PA management (see Chapter 3) to attract investment and technical capacity (Baghai et al. 2018). These CMPs vary in structure and approach. Due to the severe financial impact of COVID-19 that has put additional strain on PA authorities, along with the proven success of CMPs over the past two decades, governments have greater interest in exploring strategic CMPs, and there is a growing demand from governments for partners.

1.6 - Target Audience

Governments

The Toolkit is designed to help governments understand and consider whether CMPs are suitable for their PA estate and the process for establishing an effective partnership that will result in enhanced PA management and green growth. The target government audience includes staff working for agencies in charge of PAs, as well as those engaged in PPPs who can help leverage existing efforts already widely used in other economic sectors. As the stewards of national PA estates, governments have the ultimate decision-making authority for entering CMPs. While the focus of the Toolkit is African PAs, the tools and approaches outlined can be applied around the world. Given that CMPs attract investment capital and donor funding, the Toolkit will also help relevant ministries, such as the ministries of finance, planning, and procurement, understand the role CMPs play in creating an enabling environment for investment.

NGOs, private sector, and community partners

The Toolkit can also help NGOs and private sector partners interested in collaborating with governments understand CMP best practices. While the Toolkit references government PAs, the processes and practices can be adapted and used for private and community conservation areas and PAs I-VI, as defined by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (see Appendix A, Table A.1). A case study of a CMP between a community in South Africa, the Makuleke Community, and a PA authority, SANParks, is provided in Appendix D, Figure D.7. In addition, while the text refers mainly to terrestrial PAs, CMPs are already being used for marine PAs, such as Bazaruto Archipelago National Park in Mozambique.

CMPs are demonstrating positive conservation, social, and economic outcomes, and there is greater scope for their use across Africa and globally. Despite the proven success and heightened interest in CMPs, there are limited resources on CMPs in Africa and frequent misunderstandings regarding their structure (Resource Box 1.1). The Toolkit aims to provide information that will help enhance the use of CMPs to ensure that PAs are sustained and thrive in the future.

Resource Box 1.1 Global Wildlife Program CMP Resource Guide

The Global Wildlife Program’s CMP Resource Guide provides descriptions of and links to relevant CMP literature. www.worldbank.org/en/programs/global-wildlife-program.

1.7 - Key Terms

Collaborative management partnerships (CMPs) refers to when a PA authority (government, private, community) enters into a contractual arrangement with a partner (private or NGO) for the management of a PA (Baghai et al. 2018). Through a CMP, the PA authority devolves certain management obligations to the partner and the partner takes on these management responsibilities and in most cases funding obligations. The duration of the contract varies and is dependent on the PA and the goal of the PA authority. While the Toolkit mainly refers to public PAs, the process and principles can be adapted and used for community and private conservation area CMPs. The term CMP includes two key words that are critical to the long-term success of any management agreement — collaboration and partnership (Lindsey et al. 2021).

There are three kinds of CMPs (Baghai et al. 2018):

Financial and technical support , where the state retains full governance authority and the private partner provides technical and financial support.

Co-management CMPs , where the state and the partner collaborate on the management of the PA. This is further differentiated as follows:

• Bilateral CMPs, in which the state and the partner agree to collaborate on PA management and the two parallel entities and structures (the state and the partner) work side-by-side in the PA with a management agreement.

• Integrated CMPs, in which the state and the partner agree to collaborate on PA management through a management agreement and create a special purpose vehicle (SPV) to undertake management, with equal representation by the parties on the SPV board.

Delegated CMPs , similar to integrated CMPs, but in the case of a delegated CMP, a majority of the SPV board is appointed by the private partner.

Community partner refers to a community that lives in and/or around a PA and is engaged in a CMP in the governance and/or management of a CMP, as a beneficiary, or as the owner of a PA, legally or customarily.

Concession is a term used in PAs to describe a contractual arrangement (lease, license, easement, or permit) between a tourism operator (consumptive and non-consumptive tourism) for the use of an area for commercial purposes (accommodation, food and beverage, recreation, education, retail, and interpretive services) (Spenceley et al. 2017). A concession can be structured as a PPP.

Contracting authority (CA) refers to the government entity that has the legal authority to enter a CMP and, in some cases, depending on PPP legislation, is the entity tasked with overseeing the PPP process. In the case of CMPs, the CA often refers to the PA authority or a relevant ministry, such as the ministry of environment or finance. This term is used interchangeably with public partner.

Park or PA manager refers to the warden or the conservator of the public PA.

Private partner or party (a non-state actor) refers to the private sector partner or an NGO partner that engages in a CMP with a government body that has jurisdiction over a PA.

Public partner or party refers to the state actor responsible for PA management such as the PA authority or the relevant ministry, such as the ministry of environment. This term is used interchangeably with contracting authority.

Public-private partnership (PPP) is broadly defined as a long-term contract between a partner (private, NGO, or community) and a government entity for providing a public asset or service, in which the partner bears significant risk and management responsibility and remuneration is linked to performance (WBG 2017). The term is commonly used in the for-profit context for large-scale public works projects, which can create confusion when applied to conservation. PPPs also describes tourism concessions in PAs in some contexts, as well as blended finance models between public and private donors (Spenceley et al. 2017).

Unlike traditional PPPs for large infrastructure projects, conservation PPPs aimed at restoring and managing PAs are not profit-seeking and the partner is commonly an NGO. When the NGO partner engages in profit-making activities, such as tourism, revenues are re-invested in the conservation of the PA or sustainable development of local communities (Baghai 2021).

1.8 - Approach

The Toolkit was developed through: (i) a review of existing literature on PA management, CMPs and tourism concessions; (ii) consultation with conservation management practitioners (government and PA authorities, NGOs, community members, donors, and private sector partners) with experience establishing and managing CMPs in Africa; and (iii) a review of PPP toolkits and lessons learned from other sectors and regions.