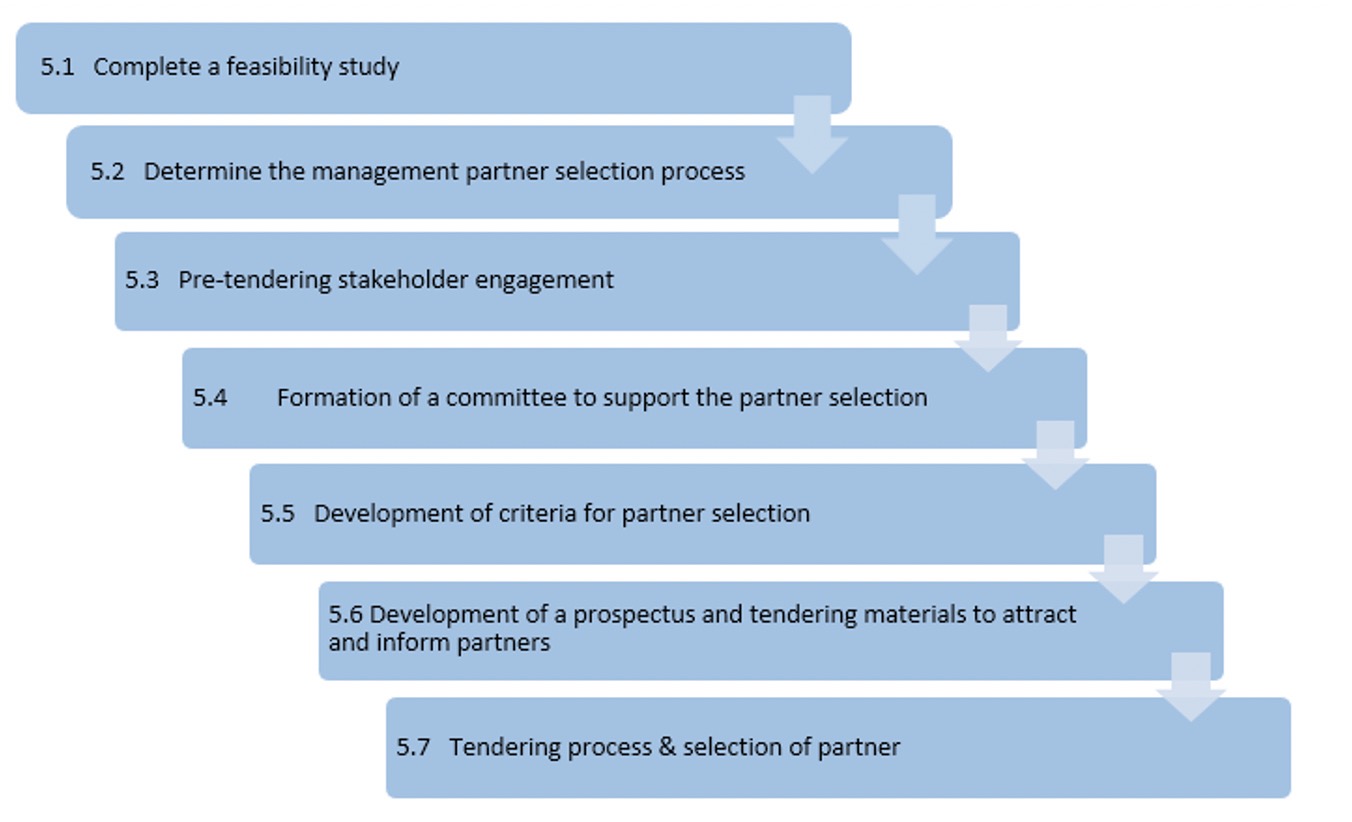

Preparing a CMP involves seven steps that are outlined in this chapter, from completing a feasibility study, to determining the selection process, to selecting a CMP partner. There are two also steps in entering into a contract and managing the partnership. All of these steps are outlined in detail. Tools are provided to help facilitate a transparent and effective process for preparing and establishing CMPs.

Following the identification and screening process (see Table 5.1), the CA will start to prepare for and establish the CMP, which is guided by the relevant country’s legal framework.

Table 5.1 - Completed Checklist for Identification and Screening of CMPs

|

Process |

Chapter |

Section |

Step |

Complete |

|

Identify and Screen CMPs |

Chapter 4 |

4.1 |

Government decision to engage in a CMP |

Ö |

|

4.2 |

Legal review |

Ö |

||

|

4.3 |

Review agency goals and targets |

Ö |

||

|

4.4 |

Screen and select potential PAs for CMPs |

Ö |

||

|

4.5 |

Screen and select CMP models |

Ö |

||

|

4.6 |

Review regional plans |

Ö |

|

Process |

Chapter |

Section |

Step |

Complete |

|

Identify and Screen CMPs |

Chapter 4 |

4.1 |

Government decision to engage in a CMP |

Ö |

|

4.2 |

Legal review |

Ö |

||

|

4.3 |

Review agency goals and targets |

Ö |

||

|

4.4 |

Screen and select potential PAs for CMPs |

Ö |

||

|

4.5 |

Screen and select CMP models |

Ö |

||

|

4.6 |

Review regional plans |

Ö |

As noted in Section 4.2, in many countries CMPs are guided by PPP legislation, which may outline a process for engaging a partner. This needs to be considered along with the process outlined in the Toolkit, Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Seven-Step Process for Preparing a CMP

Source: Conservation Capital 2016; Spenceley et al 2017; Spenceley et al 2016.

5.1 - Complete a Feasibility Study

Depending on the legislation guiding the establishment of a CMP, a feasibility study might be required by the government to demonstrate why a CMP is needed. This is common if the CMP is guided by PPP legislation. All of the work undertaken in the identification and screening process (see Sections 4.1-4.6) can be used to complete a feasibility assessment. The feasibility study needs to strike a balance by being specific (which tends to make the remainder of the process much easier), but at the same time avoiding a pre-determination of the outcome, which the market should determine. Additional information might be required under the legislation, which includes the submission and approval process. The subsequent steps follow approval of the CMP by the relevant government authority.

5.2 - Determine the Management Partner Selection Process

Approaches a government can use to engage a management partner include public tendering, direct negotiation, or auction. The Toolkit recommends a public tendering process, when a partnership opportunity is publicly advertised and a partner is selected via a competitive and transparent process. Some countries require a public tendering process for the engagement of a CMP partner for a national PA. Table 5.1 outlines the different mechanisms that might be used to attract CMP partners and the pros and cons of each approach. If done properly, a public tendering for national and international bidders, even when not legally required creates transparency, enables the CA to drive the process, and determine the best possible CMP candidates, providing the highest value for money.

The perception exists that a tendering process takes longer than direct negotiation with a potential partner, which is generally incorrect. A well-prepared and implemented tendering process has a clear timeframe, steps, and procedures, while one-on-one negotiations often take years for CMPs because the process is unclear, lacks transparency, and in some cases, government representatives stall on making a decision because of the lack of clarity and fear of negative repercussions. An unclear process also can create opportunity for corruption.

Even when a partner has been active in a PA for a long period, has invested significant capital, and knows the PA well, a tendering process will help this partner, if selected, avoid misperceptions about its engagement with government and potential challenges in the future that could either delay or derail a CMP. In addition, a tendering process helps the government take ownership of the process, assess the best bids, and drive the outcome.

Some PPP legislation contains a combined approach for when a partner proposes a CMP to the CA and the CA vets the opportunity and decides to proceed with establishing a CMP. In this case, referred to as the spontaneous option in Francophone Africa, the CA uses a tendering approach and the entity that first proposed the CMP is eligible to bid.

Table 5.2 - Different Mechanisms That Might be Used by a PA Authority to Establish a CMP

|

Process |

Pros |

Cons |

|

Public Tender |

Legally required in most cases for public land |

Competitive process may deter partners because of time required |

|

Most transparent process |

Process can be timely, costly, and complicated |

|

|

Market-based system for selecting the best proposal with the highest value proposition |

Risk of attracting bidders that do not meet the criteria, with little or no experience (can be avoided through pre-qualification) |

|

|

Stimulates investor interest by inspiring confidence in the process |

Difficulty in developing objective bid evaluation criteria |

|

|

Best candidates can be selected based on multiple criteria (monetary and non-monetary) |

Limited pool of qualified CMP partners |

|

|

Proper due diligence can be done |

Transaction cost |

|

|

Unsolicited Bid |

Greater flexibility |

Lacks transparency |

|

Investor already interested |

Prone to external challenges regarding transparency, favoritism, and corruption |

|

|

No marketing and promotion required |

Does not comply with law for public lands in most cases |

|

|

CA can proactively identify a partner |

Ad hoc and reactive to bids that are provided |

|

|

|

PA authority responding as opposed to driving process |

|

|

|

Inability to determine best partner, given only one is considered |

|

|

|

Risk is potentially greater for choosing an unsuitable investor, and not getting the best deal |

|

|

|

Not competitive |

|

|

Direct Negotiation (normally with an existing partner that has discussed the submission with the relevant government agency) |

Greater flexibility |

Lacks transparency |

|

No marketing and promotion required |

Prone to external challenges regarding transparency, favoritism, and corruption |

|

|

Relatively simple, quick, and direct |

Does not comply with law for public lands in most cases |

|

|

|

Ad hoc and reactive to bids that are provided |

|

|

|

PA authority responding as opposed to driving process |

|

|

|

Inability to determine best partner, given only one is considered |

|

|

|

Risk is potentially greater for choosing an unsuitable investor, and not getting the best deal |

|

|

|

Not competitive |

|

|

Auction |

Transparent |

Proper due diligence cannot be done |

|

Competitive |

Award goes to highest bidder, not necessarily the best partner |

|

|

Quick and easy |

Difficult to determine shared interest and vision |

|

|

Stimulates investor interest |

Not possible to negotiate other benefits (community support, job creation) |

|

|

|

May limit participation from certain parties |

|

|

|

Potential delays and need to restart the process if winners of the bidding process are unable to make payments |

Source: Adapted from Spenceley et al. 2017.

5.3 - Pre-Tendering Stakeholder Engagement

National parks and reserves are national assets and have a diversity of stakeholders, ranging from citizens who view parks as public resources, IPLCs who rely on the PA’s natural resources, private sector partners operating in and/or around the PA, local government authorities, and conservation and development organizations. Effective CMPs are built on shared trust and understanding among the stakeholders (Spenceley et al. 2016).

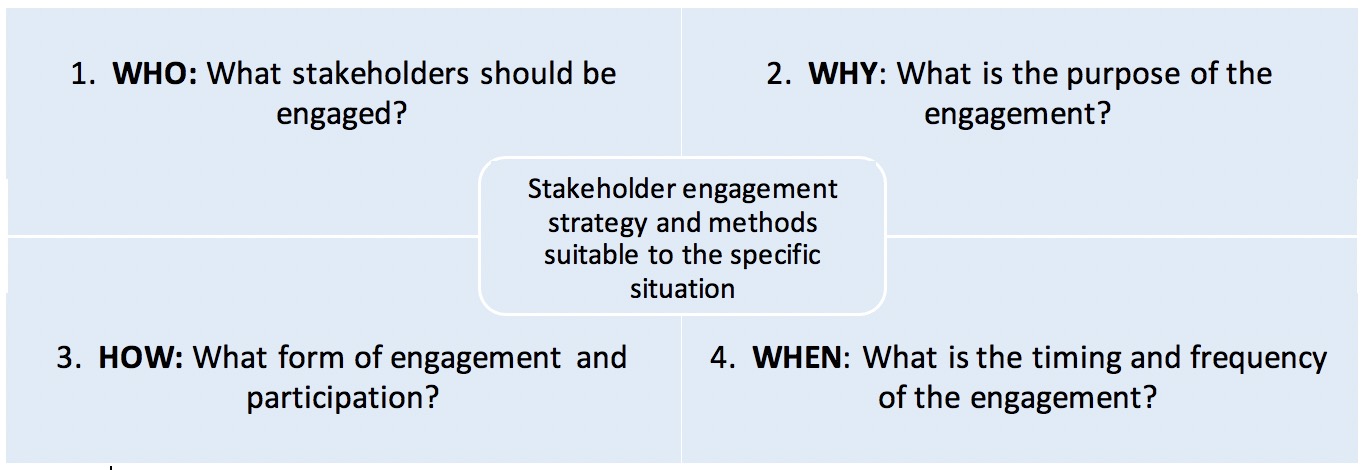

Because PAs are valuable to different groups and individuals for a variety of reasons, outlining a transparent and clear consultative process in important so that stakeholders understand and feel part of the process (see Figure 5.2). Proactive discussion and dialogue with these stakeholders can help avoid problems and delays and, in the worst-case scenario, potential legal challenges.

The first step for the CA is to identify the stakeholders, determine the best mechanisms for engagement and participation, and outline a plan for consultation. It is important for the CA to understand stakeholder concerns and to, within reason, address these points to the extent feasible.

Figure 5.2 - General Framework to Inform the Design of a Stakeholder Engagement Strategy

Source: Dovers et al. 2015.

Special consideration and consultation should be given to citizens and IPLCs that are directly and indirectly impacted by the management and governance of the PA. Chapter 6 discusses social standards that must be considered throughout the life of the CMP process. If the IPLCs have legal claims, CMPs should not be considered until the claims have been resolved or if the establishment of a CMP is part of the solution put forward by the IPLCs. The role of IPLCs can range from providing input into a management plan to serving on a governance body. Their role in a CMP should be thoroughly reviewed and considered in the stakeholder analysis and strategy. In addition, the stakeholder engagement process should ensure gender inclusivity to provide for equitable representation and participation.

The World Bank 2019 Guide to Community Engagement in Public-Private Partnerships outlines a six-step process for engagement of stakeholder communities (see Figure 5.3), which can be followed for CMPs.

Resource Box 5.1 Stakeholder Engagement

The World Bank 2019 Guide to Community Engagement in Public-Private Partnerships, a Draft for Discussion

USAID Resource Guide on Best Practices for Stakeholder Engagement in Biodiversity Programming

Partners should follow a rights-based approach that includes meaningful participation in the formulation and implementation of a CMP by the individuals and IPLCs whose lives might be affected, positively or negatively. A stakeholder engagement process should ensure that:

- Stakeholders’ concerns are captured and potential risks are adequately identified.

- Groups and peoples whose lives might be affected by the project are properly consulted to verify and assess the significance of any impacts.

- Affected groups and communities participate in the development of mitigation measures, decision-making regarding how such measures become operational, and monitoring their implementation.

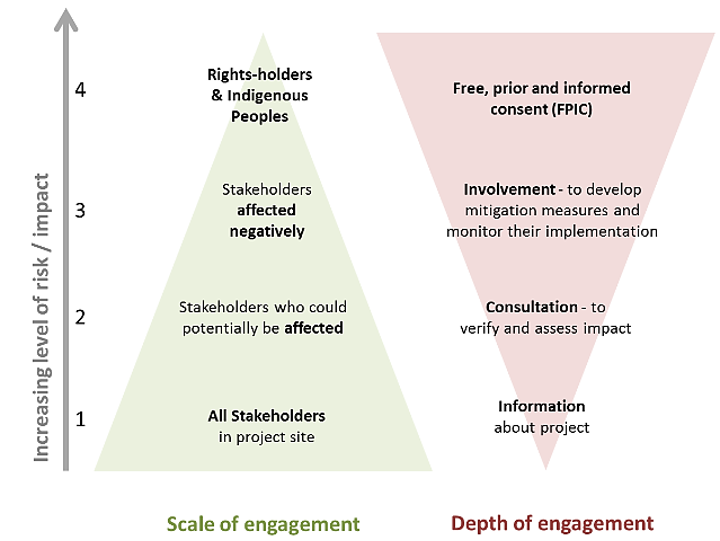

Levels of Stakeholder Engagement

The scale (extent of audience reached) and depth (intensity) of stakeholder engagement should be commensurate to the concerns expressed or expected from stakeholders and the magnitude of potential risks. The general logic of stakeholder engagement is that there is an inverse relationship between the scale and the depth of engagement as the level of risk increases (see Figure 5.4) (IUCN 2016).

Figure 5.4 - Scale and Depth of Stakeholder Engagement

Source: IUCN 2016.

All stakeholders at a project site should be provided relevant information about the project (see Figure 5.4, level 1). Stakeholders who could potentially be affected by project activities must be consulted to verify and assess the significance of adverse impacts (level 2). At this level, fewer people may be involved but they are more deeply involved. If risks and negative impacts are confirmed and judged as significant, affected stakeholders are not only consulted but are thoroughly involved in project design, including in the development of mitigation measures, and later in monitoring their implementation (level 3). If project activities take place on land, waters, or territories to which stakeholders have recognized rights (legal or customary), a process of achieving free, prior, informed consent (FPIC)

(see Chapter 6)is needed (level 4). The project manager should also ensure gender inclusivity in the consultative process (IUCN 2016).

5.4 - Formation of a Proposal Evaluation Committee

The CA should form a proposal evaluation committee (PEC) for CMP partner selection to:

● Determine criteria for partner selection.

● Review tendering documents prior to publication.

● Review expressions of interest and full invited bids from potential partners.

In some countries, the gazettement of the PEC is required. It is recommended that the PEC is made public for transparency purposes and to avoid challenges in the future, regardless of the legal requirement. The PEC must contain adequate representation from individuals with the requisite technical skills and experience to properly appraise a CMP bid. Ideally, there should also be independent experts with PA management experience. The committee should be relatively small to ensure effective operations and management. Membership of the committee should include a representative from the department within the CA that encompasses commercial development and PA planning. All members of the PEC should sign a conflict of interest declaration.

5.5 Determine Partner Criteria

The PEC will establish criteria for the evaluation of potential partners. The following criteria are suggested:

- Organizational Structure

● Potential ability to operate in the focal country (if a new private operator to a country, they may not yet be registered).

● Structure enables the partner to accept donations.

● Record of accomplishment of complying with country registration requirements.

- Technical Experience

Successful PA development and management experience is preferred, or else direct exposure to PA management projects. Given the opportunity to scale up CMPs across Africa, limiting the engagement of partners to those that have already engaged in a CMP will hinder progress. Therefore, selection should consider broader management skills.

Proven professional project management skills, including budget development, staff management and oversight, environmental management, and human resource development.

Progressive nature-based revenue development in PAs, with a particular (but not exclusive) focus on tourism development.

Proven knowledge and application of contemporary innovative conservation financing mechanisms.

Successful donor fundraising, management, and networks.

Successful, effective public relations and communications systems.

The design and application of contemporary corporate governance structures and protocols.

Proven success applying good governance procedures to operations and management.

Demonstrable professional and rigorous fiscal management and control.

- Financial Capacity

✔ Proof of funding required to support the initial period of the CMP obligation and the skills required to attract additional resources and develop sustainable revenue models.

Provision of a detailed, realistic, and professional park management business plan. Appendix J includes a description of PA business plans and tools for development.

Proof of the partners’ ability to commit long-term (20 years).

- Social Impact

Proven local community engagement, integration, and related economic development.

Proven history of optimizing local employment opportunities and positively engaging, where appropriate, with wider local community development initiatives.

Plan for capacity development of staff.

- Shared Vision and Philosophy

Demonstrated commitment to the agency’s vision and philosophy. This can be gauged by reviewing the potential partner’s work in other locations and consulting with references. In addition, the PEC will interview the partner during the tendering process, which is a good opportunity to assess whether the partner’s core values and philosophy align with the PA authority.

The PEC can develop an evaluation framework based on the partner selection criteria for each member to rank the potential partners.

5.6 Prepare Tendering Materials

The tendering materials will include the scope of the partnership and a detailed description of the project and desired responsibilities of the partner. The CA will outline in the tendering materials that it is seeking a partner to support the management of the PA and will include other targeted desired outcomes. Appendix K is a sample tendering document from the government of Rwanda. In addition to the actual tendering notice, the CA should develop information on the partnership opportunity that can be included in the advertisement and made available on the CA’s website in order to inform potential partners of a CMP opportunity and attract top candidates. At a minimum, the following information should be included:

Park location and map

Park size

Access

Ecosystem types

Wildlife

Threats

Commercial operations

Infrastructure

Number of visitors

CMP opportunity description

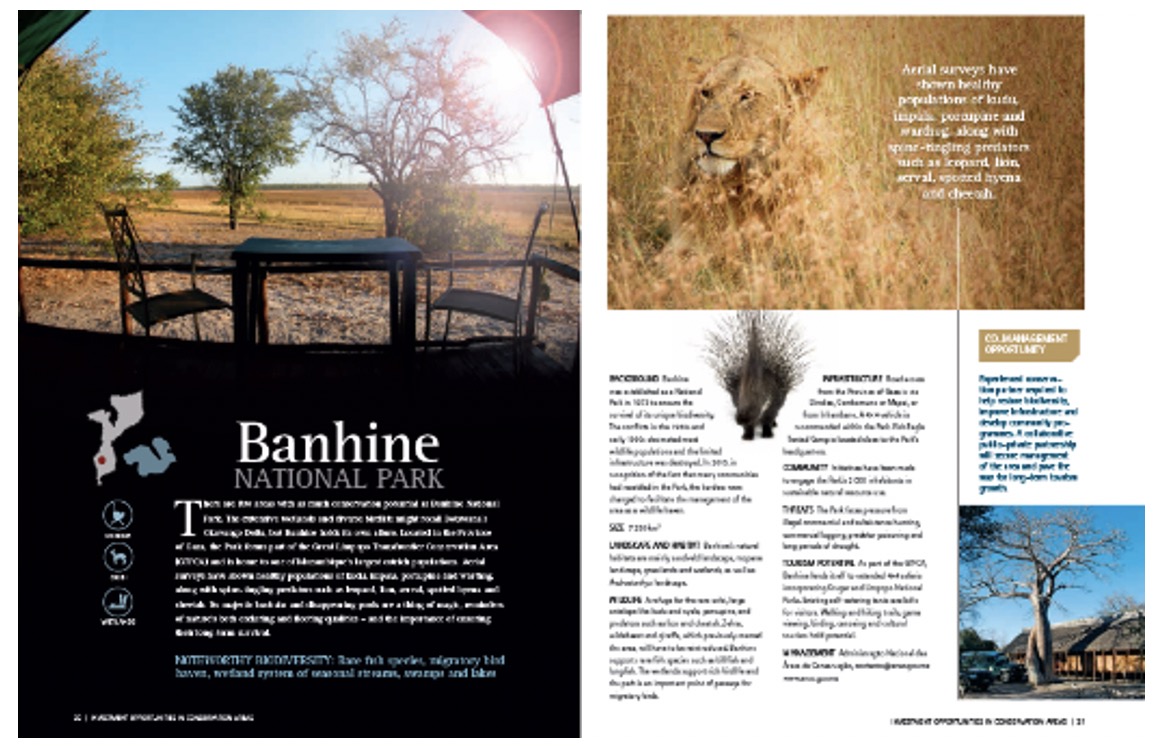

The government of Mozambique, in collaboration with the World Bank and the Global Wildlife Program , held an international conference (International Conference on Nature-Based Tourism in Conservation Areas ) in Maputo in June 2018 to maximize finance for nature-based tourism development and to promote long-term CMPs. As part of the conference, the organizers developed a prospectus that outlined tourism opportunities in eight PAs and CMP opportunities in six PAs. Figure 5.5 is the profile provided for a CMP opportunity in Banhine NP, which includes a description of and background on the park, notable wildlife, habitat type, infrastructure, size, ecosystem type, threats, and tourism potential. Appendix L includes CMP tendering materials from Uganda.

Figure 5.5 - CMP Tendering Materials from Mozambique

Source: WBG 2018.

Note: Developed for the International Conference on Nature-Based Tourism in Conservation Areas.

When the RDB advertised for a CMP in Nyungwe NP in 2019, it provided — in addition to the information referenced previously — a list of park staff, salaries, and visitor numbers to help potential partners develop an informed business plan (see Appendix J).

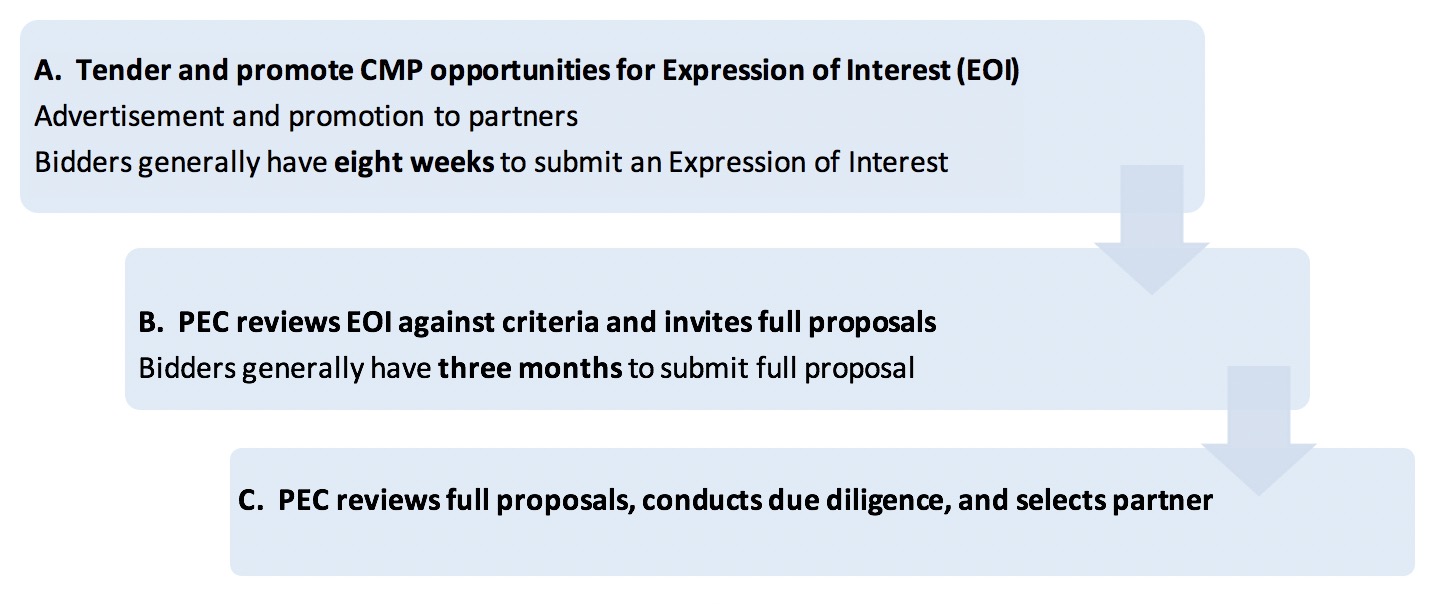

5.7 - Tendering Process and Selection of Partner

After the PEC is formed and ideally made public (see Section 5.4) and the partner selection criteria and tendering materials are prepared, the CA will advertise the CMP opportunity. The advertisement process will be guided in most cases by country PPP legislation and is outlined in Figure 5.6. In addition to public notice and advertisement, the CA can proactively notify partners about the opportunity. For example, when the RDB publicized the CMP opportunity for Nyungwe NP, it sent letters and information to a list of potential partners. Such direct contact does not replace the public notification process, but it ensures that key partners are aware of the opportunity.

Resource Box 5.2 Tendering Concessions

The tendering process for a CMP is similar to the process for engaging tourism investment partners. Spenceley et al. 2017 provides a comprehensive framework for developing effective tourism partnerships and concessions in PAs.

Guidelines for Tourism Partnerships and Concessions for Protected Areas: Generating Sustainable Revenues for Conservation and Development

https://www.cbd.int/tourism/doc/tourism-partnerships-protected-areas-web.pdf

Spenceley et al. 2016 is An Introduction to Tourism Concessioning: 14 Characteristics of Successful Programs

Successful CMP tendering process (Spenceley et al. 2016):

- Is transparent, fair, and well-governed.

- Is based on the legal framework of the country.

- Follows a thorough stakeholder engagement process.

- Is supported by experienced technical consultants and advisors.

- Engages an experienced committee with clear roles and responsibilities.

- Outlines clear selection criteria for awarding the concession to a partner.

- Is competitive.

Figure 5.6 - CMP Tendering Process Figure 5.6 CMP Tendering Process

Source: Conservation Capital 2016; Spenceley et al 2017; Spenceley et al 2016.

A. Expression of Interest

Once the CMP opportunity is advertised, partners will submit an EOI. The time allowed for the submission of the EOI is guided by the legal framework in the country, and generally is eight weeks. In PPP legislation, this is commonly referred to as the pre-selection of bidders phase and an additional step might be required to first preselect bidders (to ensure they qualify to submit an EOI), followed by the EOI. Where feasible, combining these steps is efficient and saves time and cost. During this phase, the PEC will be mainly reviewing the credentials of the bidders, whereas during the review of full bids the PEC will be assessing the plans and proposals. Figure 5.3 includes a list of the key components to be included in the EOI and Appendix M includes a detailed description. Appendix N includes a sample EOI evaluation form.

Table 5.3 - Key Components that Should be Included in an Expression of Interest

|

Category |

Key Component |

|

Partner Description |

|

|

|

Partner identity |

|

|

Key people’s biographies and CVs |

|

|

Experience |

|

|

International best practices |

|

|

Experience in target PA |

|

|

Conflict of interest declaration |

|

|

References |

|

Technical Capacity |

|

|

|

Protected area management |

|

|

Local community |

|

|

Revenue |

|

|

Fundraising |

|

|

Conservation finance |

|

|

Start-ups |

|

|

Technology |

|

|

Business and PA planning |

|

|

Environmental and social standards |

|

|

Project management |

|

Project Description |

|

|

|

Key priorities |

|

|

Alignment with PA authority |

Source: Adapted from: Conservation Capital 2016; Spenceley et al 2017; WBG 2020b.

B. Full CMP Bids

After EOIs are submitted, the PEC will review the bids against the criteria. The PEC will use the evaluation framework it developed based on the partner selection criteria (see Section 5.5) that enables committee members to rank the bids. The PEC will then solicit full bids from qualified partners. Table 5.4 includes the key components that should be included in a full CMP bid and Appendix O includes a detailed description.

Table 5.4 - Details to be Included in a Full CMP Bid

|

Category |

Key Components |

|

Corporate and Governance |

|

|

|

Proposed corporate structure |

|

|

Proposed governance structure |

|

|

Statutory compliance |

|

|

SWOT analysis of the PA and the proposed CMP |

|

Key Policies |

|

|

|

Ethics that will govern the proposed CMP |

|

|

Key people’s biographies and CVs |

|

|

Conflict of interest declaration or lack thereof |

|

PA and Stakeholder Management |

|

|

|

Proposed goals, impact objectives, and key performance indicators |

|

|

Management and human resources structure description and model |

|

|

Conservation development and management plan |

|

|

Stakeholder management plan |

|

|

PA authority capacity development plan |

|

|

Exit transition plan |

|

Finance |

|

|

|

Operating revenue development model |

|

|

Financing and business plan |

|

ESS and Risk |

|

|

|

ESS policy and strategy |

|

|

Risk management plan (see Box 5.1) |

|

|

Environmental impact plan |

|

|

Communications and reporting plan |

|

|

Lesson-sharing plan |

|

|

Marketing plan |

Source: Adapted from: Adapted from: Conservation Capital 2016; Spenceley et al 2017; WBG 2020b.

C. Partner Selection Process

Evaluation Process

Like the EOI review process, full bids will be reviewed against clear criteria established prior to the invitation for bids. During both steps of the tendering process, the EOI and the full bid, the CA will want to facilitate field visits so that partners can visit the site and understand the context. In addition, this is an opportunity for the CA to become more familiar with the partner. During the review of the full bids, the CA and the PEC will want to have a physical presentation session with the partner, giving the PA authority the opportunity to ask further questions and to meet the potential partner.

Due Diligence

After the evaluation process and once a decision has been made on a preferred bidder, the CA will undertake proper due diligence to verify the claims made in the bid, including but not limited to the provision of proof of financing. This should be done prior to any kind of commitment or contracting. A minimum of three references should be contacted. Too often this due diligence is not properly undertaken, significantly increasing the risk that the concession will not be optimally developed (Conservation Capital 2016).

5.8 Establishing a CMP

CMP Contract Development

Once the PEC selects the partner and the CA has completed thorough due diligence on the potential partner, the CA will lead in negotiating and developing the actual legal contract that binds the CMP. The content of the contract will be guided by the legal framework of the country, and contracts will vary depending on the kind of CMP model selected by the PA authority. If the CA does not have internal capacity, it should contract a CMP expert to support the contracting process. Table 5.5 includes the standard headings in a CMP contract, and Appendix P includes a detailed description of the key aspects to include in a CMP contract. Contracts should be concise and explicit to avoid any confusion and conflicts of interpretation.

Table 5.5 - Standard Headings in a CMP Contract

Source: COMIFAC 2018; Spenceley et al 2017; WBG 2020b.

5.9 Contract Management and Monitoring

Managing a contract helps ensure that a mutually beneficial relationship exists between the PA authority and the partner (Spenceley et al. 2016). Contract management also enables the partners to swiftly mitigate challenges, adapt as needed, and in the worst-case scenario, terminate a CMP agreement if needed. Contract management and performance monitoring includes two key components: monitoring and evaluation (M&E) and audits. The PA team generally completes the M&E and an external expert completes the audit. Using both approaches with a CMP is recommended, as it enables the partner to regularly track progress and thwart any challenges, while also benefiting from an external assessment of progress against the CMP contract.

Box 5.1 Risk Management

Risks in the CMP process (see Table B5.1) can lead to costly delays, work stoppages, threats to the operation, negative publicity, and reputational harm to both partners. A successful process to develop CMP agreements must include effective risk management by identifying, mitigating, and monitoring risk through stakeholder engagement, site assessments, regular reporting, adequate due diligence, and employing experienced/reputable technical personnel. This is a continual process throughout the life of a CMP.

The CA should pay particular attention to the risk management plan outlined by the potential partner in the bidding process to determine if the risk analysis is extensive and covers all the potential risks, and if the potential partner’s strategies for mitigating the risks are adequate.

Table B5.1 - CMP Risks and Mitigation Measures

|

Category |

Risk |

Mitigation Measure |

|

Financial |

An inability for the partner to secure capital, or to make payments. Currency fluctuations also pose a risk |

Proof of funding from the partner in the bid |

|

Proper due diligence during the bidding process on the partner, and verification of capital and fundraising experience |

||

|

Political |

Political interference, unrest, or sudden policy changes |

Transparent and competitive CMP selection process signed off by relevant ministries |

|

Effective engagement of relevant government entities, i.e., ministries |

||

|

Solid legal contracts that minimize the ability for political interference |

||

|

Contract termination with compensation |

||

|

Social |

Local community members are not supportive of the project and delay implementation; or lack of compliance with social standards |

Proper stakeholder engagement process |

|

Effective engagement of communities |

||

|

A partner that is committed to community engagement and has a verifiable record of positive community development |

||

|

Compliance with social standards (see Chapter 6) |

||

|

Inclusion of community representatives in the governance structure |

||

|

External |

National or international financial or security crisis, disease, and other events can impact the ability of a partner and / or the contracting agency to fulfill their obligations |

Reserve fund to support operations during crisis |

|

Security plan to ensure standard of procedures for security risk |

||

|

Clear standard of procedures to manage crisis |

||

|

Structure that allows for quick and strategic adaptive management |

||

|

Contract |

Poor quality CMP contracts that are vague, does not provide clarity on roles and responsibilities, does not anticipate challenges, and does not include clear CMP objectives |

If the PA authority lacks capacity to develop a high-quality contract, they should engage an expert to support the contract development |

|

Use best practice for contract development and refer to Annex P |

||

|

Trust |

Lack of trust between the parties. The best contracts might be in place, but if there is not trust between the parties, issues will emerge |

Proper due diligence on the partner and consultation with references, and shared vision with the PA authority |

|

Regular monitoring and evaluation (see Section 5.9) |

||

|

Conflict mitigation procedures in place and followed |

||

|

Performance |

Disagreement over performance. |

Establishment of joint work plans with clarity on roles, responsibility, and accountability |

|

Establishment of clear targets (key performance indicators) |

||

|

Routine monitoring and evaluation |

||

|

Contract termination without compensation for poor performance |

||

|

Non-Performance |

Closing out a project early |

Plan in advance for the project close out |

|

Clearly outline in the contract what happens with assets, staff, revenue, and responsibilities in case of an early termination |

Source:

Adapted from Lindsey et al. 2021; WBG 2020b. Adapted from Spenceley et al., 2016.1. Monitoring and Evaluation

a. Regular

b. Internal

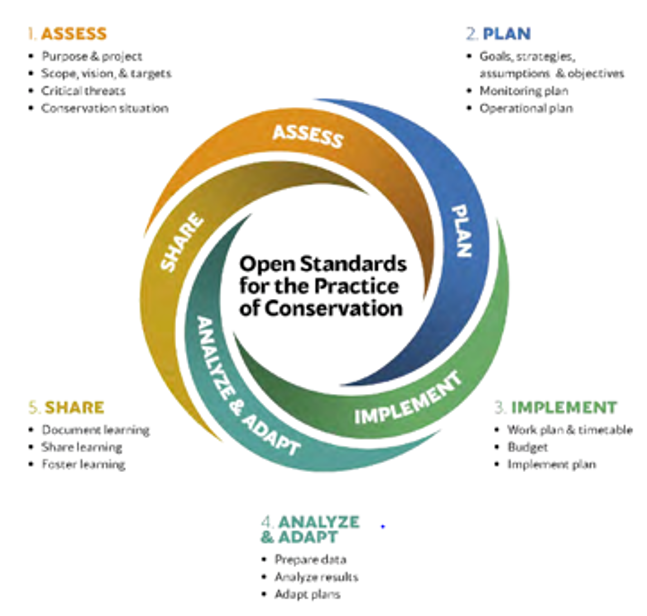

M&E should be done regularly by the CMP management team and an M&E officer (if this position exists) covering: the performance of the CMP on i) conservation, social, and ecological targets; and ii) compliance with the obligations of the contract. This is part of standard project management (see Figure 5.5). Each component will require different monitoring reports. Reports are provided routinely to the board or committee, depending on whether they involve an integrated, delegated, or bilateral CMP. The reporting timeline and frequency should be specified in the CMP and at a minimum, the board or committee should receive monitoring reports twice a year. Monitoring is done against clear targets outlined in the annual work plan and against the annual budget. The management team may also consider an internal audit every other year to assess overall performance against targets and obligations within the CMP contract.

Figure 5.7 - Project Management Cycle

Source: Conservation Measures Partnership 2020.

2. Audit

c. Every Three Years

d. External

At a minimum, an external auditor should review the CMP every three years. The auditor should be an internationally recognized PA management expert and should be jointly selected and agreed on by the partners. The audit should assess and appraise the implementation and compliance by each partner of their respective obligations contained in the CMP contract and evaluate the general performance and achievement of the CMP’s intended goals and objectives. The auditor should make specific recommendations for areas of improvement. The report should be submitted to the board or committee for approval, with a presentation made by the auditor. The cost of the evaluation should be built into the operational budget. If there is a challenge and/or an issue in implementation, the board or committee may choose to schedule an evaluation outside of the routine schedule. COMIFAC recommends in their CMP guidelines an audit every five years, which is somewhat standard (COMIFAC 2018). However, much can happen in five years; therefore, audits every three years are recommended.

Non-Compliance and/or Non-Performance

If M&E or the audit process determines that targets are not being met or a party is not fulfilling its obligations, the board or committee should work collectively to rectify the situation in good faith. This may require a change in management at park level, a shift in approach, adaptive management, or realignment of budget. Should the partners not agree on how to rectify the situation and proceed in good faith, they should follow the conflict resolution section of the CMP contract.

SMART Targets

During the planning phase (see Figure 5.7), the CMP partners will develop joint annual work plans, general management plans, and five-to-10-year business plans. To enable assessment of progress and performance, these plans should include targets that are specific, measurable, assignable, realistic, and time-related (SMART). Management targets should include targets within the following categories: i) ecological; ii) financial; iii) social; and iv) operational. SMART targets will enable the partners to adequately assess performance against the contract and help to mitigate any claims of non-performance. The establishment of baselines in the beginning of the CMP, if they do not already exist, is essential to enable project monitoring.