To enhance PA management effectiveness and reverse the trends of biodiversity loss, 15 African governments have entered into strategic co-management and delegated CMPs, and there is growing interest and momentum in CMPs. This chapter outlines the benefits of CMPs, with practical examples from across Africa, and the potential challenges with their adoption and management.

2.1 - Lessons Learned from PPPs

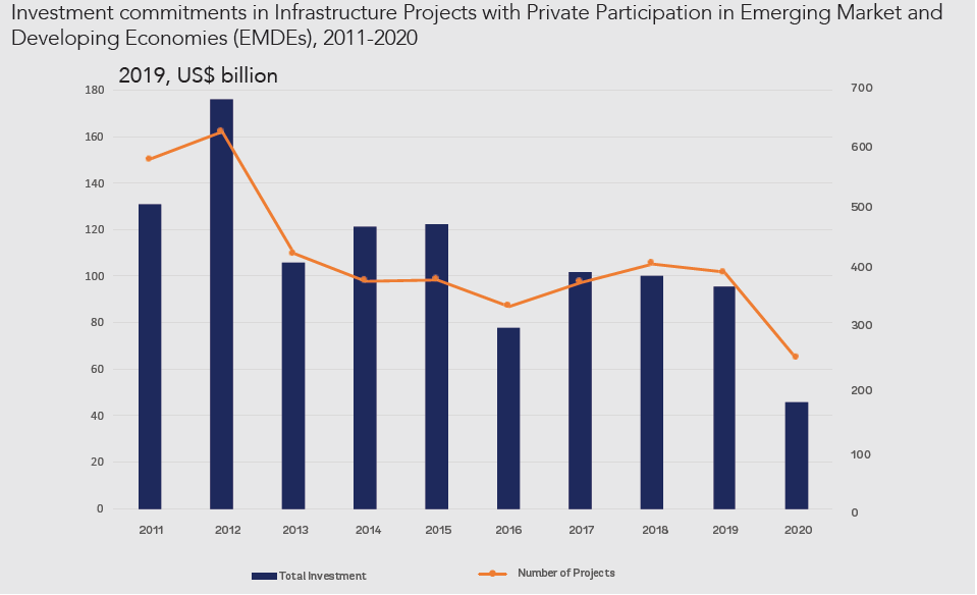

PPPs have been extensively used around the world for decades. While infrastructure (transport, telecommunications, energy, water, solid waste management) attracts the most PPPs, such partnerships are also increasing in public services such as healthcare and education, and in sectors such as tourism (concessions in PAs). See Appendix B for more details on the global PPP market.

PPPs are attractive to governments. Private investments enable governments to serve public interests without over-extending constrained budgets. They also can contribute to achieving SDGs by helping to overcome inadequate infrastructure that constrains growth (WBG 2015). In the government’s effort to reduce project costs and maximize returns-on-investment, the partner may introduce better service delivery, innovations, and implementation and operational efficiencies, while taking on a significant amount of risk and management responsibility.

At the same time, risks associated with PPPs can be high and need to be carefully assessed, mitigated, and allocated if the project continues. These include unexpected project costs or higher costs of engaging with a private partner, poor quality of results, user demand that is different than expected, changes in the legal or regulatory framework that affect the project, and default of the private partner if it cannot financially or technically implement the project (WBG 2017). Some projects are easier to finance than others, and some may be more politically or socially challenging to introduce and implement. Governments run the risk of not having sufficient expertise to understand PPP arrangements, carry out their obligations, and monitor partners’ performance (PPP Legal Resource Center 2020).

For private partners, the benefits of PPPs are linked to the ability to recoup their initial investments and satisfy the expected return-on-investments. In the case of NGO or community partners, conservation, social, or economic outcomes may also motivate the PPP arrangement, with the success of the contract linked to those goals. Partners face many of the same risks as those faced by governments, including unexpected costs, lower or different usage that affects revenue collection, and changing political or regulatory environments.

PPPs in Conservation

PAs have long permitted private companies to operate commercial concessions — for lodging, food, recreational activities, and retail — within their boundaries. A leading example is the U.S. National Park Service, which administers more than 500 concession contracts across its parks with gross receipts totaling $1 billion annually. Management concessions, in which a parks authority outsources responsibility for management or conservation activities to a partner with greater capacity, have been developed in Europe, Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Australia (Manolache et al. 2018; Wilson et al. 2008). Such partnerships, if properly structured, can help governments capture the significant economic value of parks by improving their economic sustainability, improving the quality of tourism services, leveraging investments in conservation, and contributing to biodiversity conservation (Saporiti 2006). Though PPPs are a favored mechanism, they are not always successful. Periodic reviews of PPP performance across sectors and regions offer lessons for the conservation sector.

Table 2.1 - PPP Lessons that Might be Applied to CMPs

|

Key PPP Lesson Learned |

Description |

|

1. Public sectors need enabling environments in place to apply PPPs well |

A sector’s market structures (in this case, PAs) must have conditions that allow the private sector to operate; regulatory bodies should be able to protect private partners from political interference; and public authorities should have the capacity to develop PPP projects that interest the private sector (WBG 2015). CMPs can help create the right enabling environment to attract investment, such as tourism and payment for ecosystem service investment. In some cases, the willingness of private sector tourism operators to invest resulted from a CMP. |

|

2. PPPs perform better in countries with a higher level of readiness |

Readiness refers to established frameworks (legal, regulatory, and others) in place for preparing and approving PPPs in conservation and a longer track record of PPP transactions (WBG 2015). For those countries that do not have a long track record, having strong and transparent frameworks in place is important. |

|

c. Political champions are vital for PPPs |

Given the public nature of PPPs, securing one or more political champions in government to guide and advocate for the project is essential. A review of International Finance Corporation (IFC) PPP projects found that it is rare for major projects to succeed without advocates (Florizone and Carter 2013). |

|

4. PPPs need to be backed by a sustainable business case |

Most private partners consider it vital for projects to have sound economic foundations that translate into a sustainable business model (Florizone and Carter 2013). For PPPs in the conservation sector, other motivations may be equally or more important, such as increasing wildlife numbers and improving the integrity of PAs. One factor to consider for the conservation sector is that PPPs may add or increase user charges to recoup costs. |

|

5. Partnerships should be structured to achieve public and business objectives |

Defining the right partnership model to fulfill different objectives can be challenging and requires learning from past lessons as well as innovating for the future (Florizone and Carter 2013). Within conservation, community stakeholders may need to be integrated into the partnership, because the success of the arrangement could depend on their buy-in. |

|

6. Communications about the partnership throughout is key |

The stories and success of conservation PPPs should be told early and often to people at every level — local, regional, national, and international — that can influence the project. |

In many African countries, the engagement of a CMP for PA management is guided by PPP legislation (see Appendix C). The process for establishing a CMP outlined in the Toolkit is consistent with PPP legislation.

2.2 - Opportunities and Potential Benefits of CMPs

The status quo of wildlife and PA management is not adequately addressing the conservation crisis, and traditional projects are challenged by their short-term duration and lack of accountability, among other factors. To enhance PA management effectiveness and reverse the trends of biodiversity loss, 15 African governments (see Section 3.6) and their respective ministries and agencies have entered into strategic co-management and delegated CMPs, and there is growing interest and momentum in CMPs. While CMPs have demonstrated significant positive ecological, economic, and social outcomes, they are not suitable in all cases, as described in the Toolkit, and should be considered among a suite of conservation tools. In addition, coordination between CMP partners and other PA managers in the broader landscape (public, private, and community) is important for conservation and development outcomes. Numerous drivers lead governments to engage in CMPs, as outlined below. Nine case studies are included in Appendix D, which describe various drivers for each CMP.

Economic Drivers

a. Attract donor funding and in some cases are a donor requirement

PAs with CMPs have higher operational budgets than those without. Researchers find that the median PA funding associated with CMPs is 2.6 times greater than the baseline of state funding for bilateral and integrated CMPs, and 14.6 times greater for delegated CMPs (Lindsey et al. 2021). Funding from CMPs comes from bi-lateral and multi-lateral donors, private foundations, lotteries, foundations associated with zoos, philanthropists and individual donors, and the private sector through corporate foundations and corporate social responsibility programs. In some cases, NGOs can facilitate charitable donations more easily than governments, can mobilize resources quickly to respond to a crisis, and are able to manage and account for funding in a way that governments may not. NGOs can bring financial accountability through professional financial management and audit procedures that give funders confidence their funds will be accounted for and used for the intended purpose. In addition, the development or improvement of a governance structure as part of the CMP creates additional oversight and a layer of accountability that provides assurance to donors about proper budget management.

Gonarezhou National Park (NP) in the southeastern part of Zimbabwe is managed through a CMP between the Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS) and the ZPWMA. Annual funding for the park increased in year one by 50 percent and the current annual budget is approximately $5 million, including capital expenditure.

Some donors increasingly require a CMP to be in place before providing funding for PA management.

“The Wildcat Foundation has been supporting national parks in Africa for nine years, and currently has substantial grants active in 10 parks in six countries. It is highly unlikely that we would have provided anywhere near this level of support had our NGO grantees not been partnering with African government agencies that gave them full delegated management authority for the parks. The delegated CMP gives us confidence that the parks will be expertly managed. We know the NGOs involved and can hold them accountable for how they use our funds and for the results. We know they will implement a park plan that we’ve pre-approved, and to begin creating good jobs and providing training and mentoring that will elevate the country’s own conservation professionals to become expert senior managers.”

– Rodger Schlickeisen, Director, Wildcat Foundation, a private foundation based in the United States

b. Enhance investment flow

A report titled “Mobilizing Private Finance for Nature” concluded that public funds are insufficient to reverse biodiversity loss and private sector finance can help mitigate the threat (WBG 2020c). However, the right enabling environment must be established to attract private sector finance.

Properly structured, private sector investment in PAs can increase revenue for PA management and community benefits. Poor PA management, often due to a lack of funding and capacity, deters private sector investment and perpetuates a negative feedback loop. CMPs enhance PA management, help to secure the natural assets upon which the private sector depends, and provide a long-term agreement that instills confidence for private sector partners.

The development of a CMP between African Parks and the Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) in Liuwa Plains NP (see Appendix D, Figure D.5) in Zambia enhanced the management of the PA, enabled the recovery of key species (elephants were seen in the Park in 2020 for the first time in 11 years), and as a result, attracted a new high-end tourism investment. Time + Tide developed a five-star lodge that has generated revenue for PA management and the local communities and attracted positive media coverage from Time Magazine, the New York Times, and Travel + Leisure.

“The agreement between African Parks and DNPW is a true partnership with shared commitment and risk. African Parks’ effective management of the area in partnership with DNPW assisted us with the challenge of operating in such a remote space. We return their efforts with the attraction of tourism through our brand, boosting conservation support (through park fees), showing immediate economic return, and proving to communities and governments the worth of preserving their natural capital. This is evident in the direct economic benefits through employment and procurement and educational benefits through the Time + Tide Foundation. Time + Tide is aligned with African Parks and DNPW in our interests and approach to conservation and for that, the partnership has, and will, continue to strengthen and grow.”

-- Bruce Simpson, CEO, Time + Tide, 2021

A CMP can help create an enabling environment for biodiversity offsets, which are measurable conservation outcomes resulting from actions designed to compensate for significant residual adverse biodiversity impacts due to project development after appropriate prevention and mitigation measures have been taken (Business and Biodiversity Offset Programme 2009). Infrastructure development and resource extraction is taking place across the continent at a significant pace and scale, and some private sector companies are engaging in biodiversity offsets. Supporting an existing non-operational PA or creating a new PA are often the most optimal approaches for offsetting. However, a barrier for implementing biodiversity offsets results if the PA authority does not have the capacity to manage the offset funding and to deliver on the clear and regulated offset targets. A CMP can create the right management and governance structure to channel offset funds to desired conservation actions.

In Senegal, Resolute Mining is engaged in a biodiversity offset around Niokolo-Koba NP, West Africa’s second largest national park. A CMP was developed between the National Parks Directorate and Panthera, an NGO based in the United States, along with a tripartite agreement with Resolute Mining for funding conservation activities in compliance with the biodiversity offset.

Enhanced management and a long-term CMP agreement enable partners to optimize ecosystem service opportunities, such as payment for ecosystem services and REDD+. Like nature-based tourism (NBT), these developments, if properly structured, can enhance revenue to the local economy and create jobs, as well as support PA management budgets.

c. Support government PA budgets

One of the primary reasons governments enter into strategic partnerships for PA management is to attract new funding, generate sustainable revenue models, and reduce the financial burden of PA management on the PA authority. Some PA authorities are independent parastatals required to raise capital and generate revenue, which puts enormous pressure on the agencies. In some cases, poor management choices can be the result, such as engaging a private sector partner that provides upfront funding but lacks the capacity to deliver on long-term commercial commitments. CMPs can help reduce the financial burden, enabling PA authorities to make smart, long-term management decisions.

The ZPWMA manages approximately 13 percent of Zimbabwe’s total land area. Its annual management budget is approximately $30 million, a high portion of which is salaries, leaving little in the way of operational budgets. Every year, the ZPWMA faces a funding gap (IUCN 2020a). The ZPWMA has CMPs in place for two NPs: Gonarezhou (see Appendix D, Figure D.3) and Matusadona. These parks comprise roughly a quarter of the national parks in the country; therefore, their engagement with partners significantly supports ZPWMA’s national park budget.

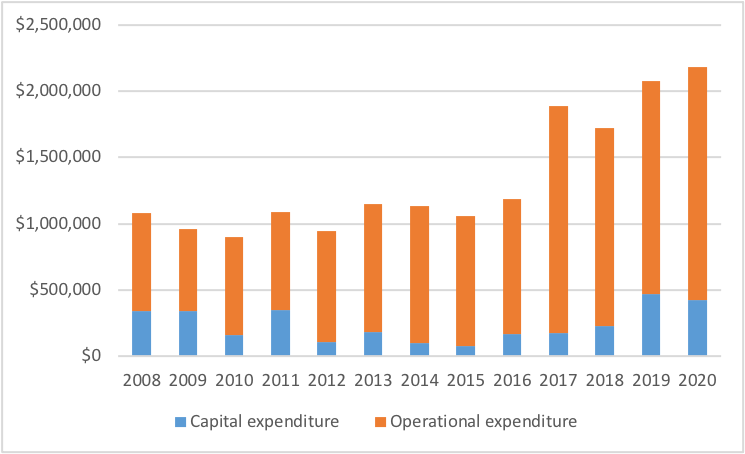

In Malawi, government investment in the PA system is almost non-existent. The average annual budget allocated from the government is approximately $325,000. The Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) has four CMPs with African Parks that have attracted significant funding to the country and converted the PAs into economic engines for the rural and national economy. The annual operating budget for 2020 for Majete NP (see Figure 2.1) is six times the total budget allocated to the DNPW for all its PAs ($310,000).

Figure 2.1 - Majete Wildlife Reserve Annual Expenditure

Source: African Parks Majete Wildlife Reserve Data 2021.

d. Increase foreign exchange, tax revenue, and employment

A functional and well-managed PA also can stimulate the rural economy, increasing tax revenue to the government and creating rural employment (Spenceley et al. 2016). This in turn makes PAs politically relevant. For example, nature-based tourism:

generates 40 percent more full-time jobs than the same investment in agriculture,

has twice the job creation power of the automotive, telecommunications and financial industries, and

provides significantly more job opportunities for women compared to other sectors (Space for Giants et al. 2019).

NBT, while not suitable for every PA, is also the largest, global, market-based contributor to financing PA systems. NBT is a major multiplier in terms of wider economic impacts. For every $1 of direct spending in PAs, including park fees, lodge nights, and activities, an additional $0.79 is spent in the local economy. In some countries, this wider impact is far higher; for every $1 spent by a leisure tourist in Uganda, an additional $2.5 in GDP is generated (Space for Giants et al. 2019).

COVID-19 has had a significant impact on NBT and PAs (Section 1.3). Support is needed to restore and adapt the industry to ensure it can withstand future shocks, and to diversify revenue sources for PAs.

While the mandate of most CMPs cover the PA, many CMP partners invest in the “buffer area,” catalyzing significant benefits for the local communities resulting from micro-finance, agriculture investment, and other enterprises.

Virunga NP , managed through a CMP between the Virunga Foundation and the Congolese Institute for the Conservation of Nature (ICCN), facilitated the development of a hydroelectric power project that stimulated small- and medium-sized enterprise growth from 90 to over 900, creating 3,400 direct jobs and 13,000 indirect jobs (Virunga Foundation Ltd 2019).

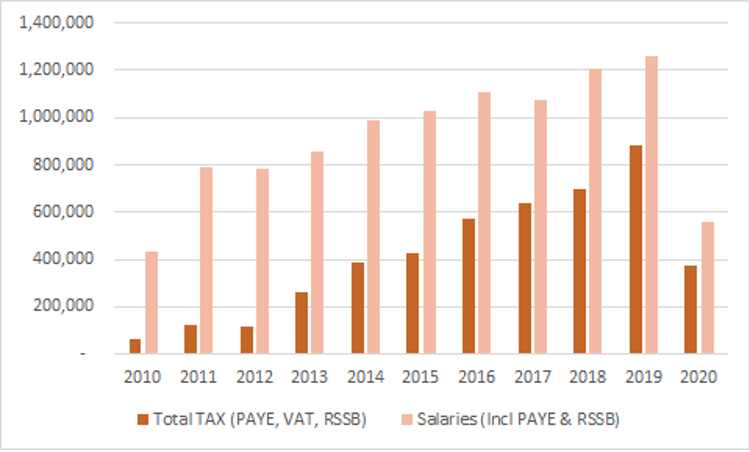

Payment for salaries in Akagera NP, managed through a CMP between African Parks and the Rwanda Development Board (RDB), and taxes to the government of Rwanda increased significantly from 2010 to 2020 (see Figure 2.2 and Appendix D, Figure D.1). Note the decline in 2020 is due to COVID.

Figure 2.2 - Revenue Generation from Akagera National Park, Rwanda

Source: African Parks Akagera NP Data 2020.

e. Create and catalyze community benefits

In addition to job creation through NBT and in the PA, CMPs have created substantial social benefit by attracting development partners who undertake social development projects or by the partner undertaking these kinds of projects. In addition, CMPs have provided support to communities in times of need. During the COVID crisis, many CMP partners have provided hand-washing facilities and other protective gear. During Cyclone Idai in 2019 in Mozambique, CMP partners provided food and helped rebuild villages.

Gorongosa NP, Mozambique (see Appendix D, Figure D.4) improved food security by engaging approximately 10,000 local farm families, generating 300 additional jobs, and developing health interventions that allow more than 100,000 people to be treated per year. In response to Cyclone Idai, Gorongosa delivered 220 tons of food and water to communities in an operation launched prior to the arrival of international aid.

Technical Support Drivers

Attract skills not currently represented in the PA agency

The most effective CMPs involve partners that bring a suite of skills not currently represented within the PA authority. For example, tourism development is a skill set that some PA authorities seek to attract through a CMP. By complementing the existing skills from the PA authority, each partner brings integral expertise, and the partnership combines and enhances the overall proficiency for PA management, development, and ultimately sustainability.

Enhance PA agency capacity

If structured properly, CMPs can and should enhance the capacity of PA authorities. CMP contracts should require, within reason, the development of capacity of the PA authority staff and the process for doing so. In addition, contracts should include the obligation to share lessons learned across the agency. CMPs can be used as a short-term bridge to help build capacity of the PA authority and management systems or as a long-term and, in some cases, a permanent solution. Regardless of the duration, capacity building of staff is a key component of long-term success.

Operational Drivers

Enhance governance and decision-making

CMPs devolve management, which separates the governance structure (whether new or existing) and oversight from on-the-ground management. That helps streamline operations and avoid decisions made for personal gain and can enable rapid decision-making without the need to refer to the central administration (Brugière 2020). Some CMPs improve or create formal governance structures that help clarify decision-making and management and command lines, enhancing management effectiveness and resulting in efficient operations and rapid implementation.

Help transform non-operational PAs

Many PAs in Africa are considered “paper parks,” meaning they exist on paper, but are non-operational. For example, KWS, one of Africa’s best-funded wildlife authorities, indicated in 2018 that 50 percent of their parks were non-operational (IUCN ESARO 2017). PA authorities can target paper parks for CMPs to attract funding and operationalize them, which will help stimulate the local economy, decrease the financial burden on the PA authority, and support the government in fulfilling its long-term regional, national, and global obligations.

Gorongosa NP, Mozambique (see Appendix D, Figure D.4) was non-operational prior to engagement in a CMP with the Carr Foundation. Wildlife was decimated during and after the Mozambique civil war, employment was minimal, and community benefits close to non-existent. Through concerted effort between the government of Mozambique and the Carr Foundation, the park is now an economic engine that supports community jobs and livelihoods and hosts extraordinary biodiversity following a remarkable ecological recovery. It has attracted positive attention to the country and is a source of pride for the government.

f. Avoid downgrading, downsizing, and degazettement

Governments need to rationalize land use and PAs that are not functioning and face the risk of downgrading, downsizing, and degazettement (DDD). In 2019, the then-president of Tanzania ordered the government to identify PAs that had no wildlife and forests and allocate them to farmers and livestock keepers (Lindsay et al. 2021). The PADDD database, which does not include all incidents of DDD, shows 296 enacted DDD events and eight proposed in East and Southern Africa across 13 countries as of 2019 (IUCN ESARO 2020b). CMPs can target non-functioning PAs that have the potential to become operational, which reduces the risk of DDD (Symes et al. 2015). This in turn can help the country fulfill its international and national conservation obligations.

Enable governments to fulfill national and global commitments

Most African governments have established national conservation targets and are party to pan-African and global treaties. The engagement of qualified partners through CMPs can help governments meet these targets. For example, all African governments are signatory to the Convention on Biological Diversity. CMPs can support governments in meeting their CBD targets, such as the Aichi Biodiversity Targets. These targets are anticipated to increase under the post-2020 global framework.

In 2015, all United Nations (UN) member states adopted the SDGs. Table 2.2 outlines how CMPs will help African governments achieve these targets. SDG Target 13 is particularly relevant given government commitments to achieving climate targets and the recognition of the significant role effectively managed PAs and healthy ecosystems play in climate mitigation and adaptation. Terrestrial PAs have been estimated to store about 12 percent of terrestrial carbon stocks and to sequester annually about 20 percent of the carbon sequestered by all land ecosystems. Nature-based climate solutions, including protection and restoration of forests and other carbon-storing ecosystems, could provide up to 37 percent of the reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions needed to stabilize warming to 2° C by 2030.

Numerous African countries, such as Rwanda, have developed green post-COVID recovery plans that include the sustainable and inclusive development of PAs. CMPs support green recovery targets, including jobs, community resiliency, and revenue diversification.

PADDD stands for PA downgrading, downsizing, and degazettement.

- Downgrading is the legal authorization of an increase in the number, magnitude, or extent of human activities within a PA.

- Downsizing is the decrease in size of a PA as a result of excision of land or sea area through a legal boundary change.

is the loss of legal protection for an entire PA.

Table 2.2 - The Impact of SDGs on CMP

Source: Adapted from https://sdgs.un.org/goals; Lindsey et al. 2021.

Enhance brand recognition

CMP partners brand and market their partnership, which helps create awareness of the PA, the partnership, and the country. In addition, tourism partners are attracted to invest in PAs with CMPs, and brand, sell, and promote the country, PA, and their tourism facility, which enhances overall brand recognition for the country. Likewise, the restoration of flagship species, as a result of improved management, can garner global recognition for the country.

The eastern black rhino was reintroduced into Akagera NP (see Appendix D, Figure D.1), which brought significant attention and media coverage to Rwanda as a tourism destination. Millions of people tracked the rhinos’ progress on social media on their journey from South Africa to the park. These positive conservation stories contribute to the country’s brand and attract visitors and investors.

The film “Our Gorongosa,” about Gorongosa NP and the CMP between the Carr Foundation and the National Administration of Conservation Areas (ANAC), was on PBS, NOVA, and CNN. In 2020, it was shown at film festivals around the world and received multiple awards, creating broad awareness about Mozambique and Gorongosa.

Reduce conflict

CMPs that engage relevant stakeholder communities in the governance model have reduced conflict between government and local communities because they generate increased accountability upward and increased legitimacy downward (Fedreheim 2017). Inclusion of local communities enhances communication and coordination, which helps to reduce misinformation that often leads to conflict around PAs. In addition, local communities often have historical knowledge about the particular landscape and invariably an understanding of dynamics in and around the PA. If relevant stakeholder communities are effectively engaged in PA governance, their knowledge can be used to support and enhance management of the PA. On the contrary, if communities are excluded, their knowledge can be used to exacerbate the threats to a PA and conflict with the management authority.

Increase security

CMPs have helped improve security in certain locations, and this has garnered local support. Unmanaged PAs create an ideal location for rebels and other insurgents, while presence and active management deter insecurity. For example, African Parks has a management agreement in the Central African Republic for the Chinko Reserve. The Central African Republic has been riddled by war, and because of the stability created in Chinko, 380 internally displaced people, mainly women and children, fled into the reserve in 2017 for protection by the rangers. After months of being provided with safety, food, water, shelter, healthcare, and employment, the displaced people voluntarily relocated back to their village with African Park’s support and assistance (Stolton and Dudley 2019).

2.3 - Potential Challenges with CMPs

Over the past two decades, African government and partners have established 40 co-management and delegated CMPs covering more than 468,500 km 2 of diverse habitats (see Section 3.6). The adoption of CMPs is the result of the financial and capacity challenges faced by PA authorities and the suite of benefits outlined in Section 2.2. In addition, some of the early CMPs, such as African Parks’ engagement in 2003 with the government of Malawi in Majete Wildlife Reserve, have provided practical examples of successful management partnerships. Despite the interest in CMPs by government, partners, and donors, challenges remain in the uptake of CMPs by governments and partners and in the management of CMPs.

Challenges with Adoption of CMP as an Approach

There has been a relatively slow uptake of CMPs for a host of reasons. These challenges were outlined in an Opinion Piece in Biological Conservation (Lindsey et al. 2021) and are highlighted below. Brugière (2020) notes that there is low cultural and political acceptance of CMPs in French-speaking countries in Africa because of the historical and current role of the central government and the perception that CMPs, in particular the delegated model, are an attack on national sovereignty.

Table 2.3 - Challenges for the Adoption of CMPs in Africa

|

Challenges for Adoption of CMPs |

Clarification and Potential Mitigation Measures |

|

|

1. Government concern |

||

|

|

There is a perception that entering into a CMP means giving away national assets and relinquishing too much control |

National PAs are national assets and a CMP does not change its ownership. The government is the ultimate authority that determines which CMP model is appropriate for the PA and this in turn determines the level of “control” transferred to the partner and for what duration |

|

|

Some governments perceive that entering into a CMP is a sign of “failure” or a reflection on their inability to achieve their own objectives |

PA authorities across Africa face enormous challenges due to a lack of resources and escalating threats (see Chapter 1). A CMP is a strategic conservation tool that can help governments improve management of PAs, build national capacity, assist PA authorities in meeting their national objectives, and support a green recovery after COVID |

|

|

Concern about revenue retention at the PA level |

|

|

|

Concern that CMPs do not build capacity of the PA authority |

A well-structured CMP should and can build the capacity of the PA authority. When the government is developing the CMP agreement, capacity building of the PA authority can be a key target with clear indicators for measuring success |

|

2. Lack of qualified private partner |

||

|

|

The success of a CMP depends on a qualified NGO or private partner that shares the same vision as the PA authority and has the technical capacity and the ability to attract funding |

NGOs that have not engaged in a CMP should start by providing a PA authority with technical and financial support and learn about the PA and management needs and build the expertise required. African Parks is mentoring some smaller NGOs to help build capacity for these organizations in CMPs. NGOs engaging in CMPs should share successes and failures so that other NGOs can learn from these experiences. There is a need for a greater focus among NGOs and donors on developing capacity for PA management as the core of conservation and building the capacity of national organizations |

|

3. Lack of donor funding |

||

|

|

The success of a CMP depends on adequate and long-term funding |

There is a huge funding gap in PA management and most donor support is short-term, which is problematic for long-term CMPs. Ideally, donor funding will increase following increased awareness of the ecological, economic, and social success of CMPs. In addition, CMPs create an enabling environment to attract private sector investment |

Source: Adapted from Lindsey et al. 2021.

Challenges with CMP Development and Management

While CMPs have demonstrated success (see Section 2.2), there are challenges in the development and management of such significant partnerships. Learning from these challenges is key to ensuring future CMPs can avoid or navigate potential barriers. Therefore, it is important that forums and platforms exist for CMP partners to share challenges they faced and how they dealt with them.

Table 2.4 - Challenges in the Management of CMPs

|

Category |

Element |

Reasons |

Mitigation Measures |

|

A. Agreements and CMP structure |

Agreements |

Informal or expired agreements that do not give partners and donors confidence to make significant investments |

Agreements should be legally binding |

|

Short-term agreements, which limit the ability of the CMP to define and implement long-term visions and strategies and fail to inspire private investor confidence in the long-term prospects of the PA |

Agreements should be at least 20 years and, in some cases, longer depending on the context |

||

|

Agreement lacks clear division of roles and responsibilities, leading to confusion, conflict, mistrust, blurred accountability, or partners placing blame |

Agreements should clearly outline roles, responsibilities, and accountability of each partner |

||

|

Insufficient delegation of authority |

Weak mandate given to or requested by the partner, with insufficient responsibility to address the scale of challenges facing the PA |

The mandate for management of programs must be clear in the agreement and adequate to address the challenges, which requires proper planning |

|

|

Government retains (or NGO decides not to assume) authority and responsibility for critical aspects of management, but lacks sufficient resources |

Parties must have suitable capacity and resources to fulfill their mandate |

||

|

Lack of sufficient authority over PA management, making decision-making vulnerable to political interference and bureaucratic delays |

CMP agreements should delegate sufficient authority for decision-making and management based on the threats and PA needs |

||

|

Poorly designed models |

Premature withdrawal of a partner before capacity of the PA authority is sufficiently built |

Proper due diligence by the government on the partner’s ability to fulfill its mandate. Capacity building of the PA authority should be a core aspect of agreements, and there should be adequate time allocated for transitioning agreements |

|

|

Bilateral CMP models often result in confusion, conflict, and other challenges in which NGOs and governments operate as separate entities with parallel authority hierarchies and separate human resources policies and pay scales |

CMPs must make roles and responsibilities clear. If there are dual structures in a PA, the policies of each partner should mirror the other, to the extent possible |

||

|

Multiple partners in the same PA without a plan |

Multiple NGO partners operating in the same PA and focusing on similar activities, leading to confusion, duplication of effort, and inefficiencies |

If the government engages multiple partners, roles and responsibilities must be clear, and there should be a tripartite agreement to ensure effective communication and coordination |

|

|

B. Government support |

Insufficient government buy-in and support |

Lack of support from the government relating to permits and other administrative elements |

Government support is critical for the success of the CMP |

|

Lack of shared vision at higher government levels regarding sensitive issues such as settlements and oil and mining inside the PA |

The partner should conduct a detailed risk analysis prior to entering a CMP |

||

|

CMPs negotiated from top down without buy-in at headquarters (HQ) level or park level can undermine the functioning of the CMP |

Support from all levels of the PA authority/government needs to be clear and genuine prior to engaging in a CMP |

||

|

C. Community support |

Lack of community support |

Lack of support from stakeholder communities can present significant challenges to the CMP, resulting in delays, expenses, and legal challenges |

Proper stakeholder consultation, following accepted global standards, should be conducted prior to engaging a partner, and social standards should be in place. Community engagement in the governance model should be considered to enhance coordination and support |

|

D. Civil society support |

Lack of civil society support |

National PAs involve a diversity of civil society members with strong opinions about and passion for PAs. Lack of support from civil society members can present challenges to the CMP, resulting in delays, expenses, and legal issues |

Proper stakeholder consultation should be conducted prior to engaging a CMP partner, and transparent communication about the rationale and CMP process is needed continuously to ensure a clear understanding by civil society |

|

E. NGO capacity |

Insufficient NGO expertise in PA management |

Lack of NGO expertise or experience in PA management can translate into an inability to effectively attract skilled personnel and provide necessary support to field staff, as well as the inability of a partner to fulfill legal CMP obligations |

CMP partner selection must be rigorous to ensure partners have adequate expertise to fulfill their mandate |

|

F. Finance |

Insufficient funding |

Insufficient budgets relative to the size and complexity of the PA and levels of threat |

Partners must demonstrate, as part of their bid, proof of finances for the initial stage of the CMP and the capacity to develop sustainable revenue streams |

|

Funding gaps |

Short-term CMPs that are periodically renewed, and CMPs that rely exclusively on large institutional funders, can suffer from a lack of continuity in funding, which can lead to staff layoffs and management setbacks |

Partners must demonstrate, as part of their bid, proof of finances for the initial stage of the CMP and the capacity to develop sustainable revenue streams |

|

|

G. Context |

Overly complex contexts |

Severely complicated scenarios, such as political instability or high densities of people and livestock inside PAs, can present challenges beyond the ability of a private partner (and in some cases governments) to overcome |

The PA authority and the partner should conduct a detailed risk analysis prior to entering into a CMP and determine the feasibility of achieving targets |

|

H. Relationships and trust |

Breakdown of relations |

Breakdown of relations or trust between partners, leading to paralysis or the end of the partnership |

The CMP should outline a clear conflict resolution process |

|

Errant behavior by one or both partners |

Partners not fulfilling pledges; issuing inappropriate external communications; not acting in the spirit of cooperation; and acting outside the law. Other issues include a lack of data sharing, joint planning, budget development, fundraising, and genuine collaboration |

The CMP should outline a clear conflict resolution process. Operating outside of the agreement should constitute a violation with clear means of terminating the agreement as needed |

|

|

I. Enabling environment |

Lack of clear process to establish CMPs |

The lack of clear guidelines and process for establishing a CMP leads to delays and in some cases, donor fatigue, resulting in a loss of finance for the CMP |

Governments interested in CMPs should create the right enabling environment for the transparent adoption of CMPs |

|

Lack of supportive legal framework to manage CMPs |

Legal framework not in place to protect and manage the CMP long-term without political interference |

Governments interested in CMPs should create the right enabling environment for effective management of CMPs |

Source: Adapted from Lindsey et al. 2021.