This chapter describes the three primary CMP models used in Africa, and highlights their strengths, weaknesses, and risks. Three case studies are presented to compare the models. Twenty-four best practice principles for CMPs are featured for practitioners to consider in CMP development, management, and closure. The status of CMPs in Africa is provided, highlighting 40 co-management and delegated CMPs, the partners, regional distribution, models used, trends, and projected CMP pipeline.

3.1 - Differentiating between Governance and Management

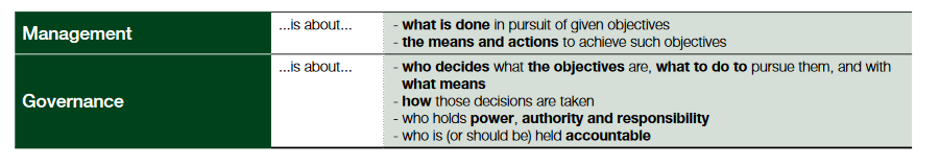

A CMP requires consideration of the existing and desired governance and management structure for a PA. The governance and management of PAs are closely linked; however, for a successful CMP, it is important to understand the difference and to distinguish this in the CMP agreement. Governance is about broad, strategic decision-making, while management is about implementation (see Table 3.1) (Borrini-Feyerabend et al. 2013).

Table 3.1 - Management and Governance of PAs

Source: IUCN 2013.

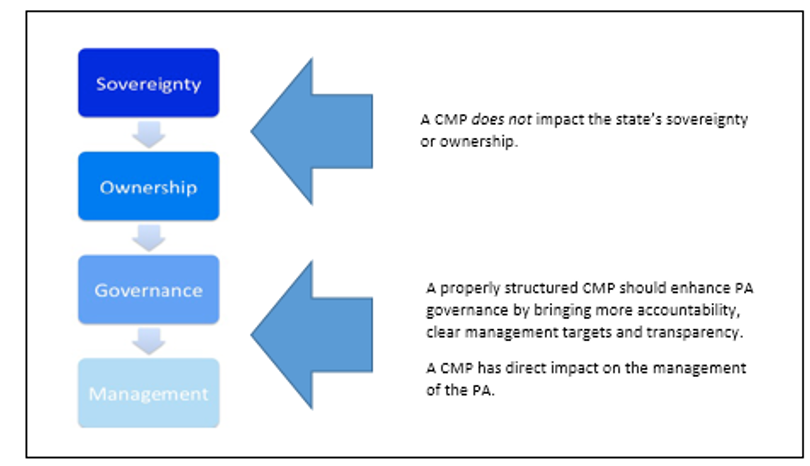

Governance goes beyond just understanding who makes certain decisions around PAs to include interactions among structures, processes, and traditions that determine how power and responsibilities are exercised, how decisions are taken, and how citizens and other stakeholders have their say (Borrini-Feyerabend et al. 2013). While CMPs affect the management and governance structures of a PA, they do not alter a nation’s sovereignty or ownership (see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 - CMP Governance and Management

Source: Adapted from original source Baghai 2016; Borrini-Feyerabend et al. 2013; IUCN ESARO 2017.

There are four types of PA governance structures: governance by government; shared governance; private governance; and governance by indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs) (see Table 3.2).

Table 3.2 - The Four Types of Protected Area Governance Models and Examples from Africa

|

Type |

Description |

Examples |

|

Governance by government |

● Federal or national ministry or agency in charge ● Sub-national ministry or agency in charge (e.g., at regional, provincial, municipal level) ● Government-delegated management (e.g., to an NGO) |

1. The government manages most national PAs in Africa. For example, the Kenya Wildlife Service manages Kenya’s national parks and national reserves 2. Delegated management includes the management agreements with African Parks in Malawi, Rwanda, Republic of Congo, Chad, and other countries in Africa |

|

Shared governance |

● Transboundary governance (formal arrangements between one or more sovereign states or territories) ● Collaborative governance (diverse actors and institutions work together) ● Joint governance (pluralist board or other multiparty governing body) |

A. Collaborative governance includes bilateral and integrated co-management; for example, FZS in Gonarezhou, Zimbabwe and African Wildlife Foundation in Simien Mountains NP, Ethiopia B. The Greater Virunga Transboundary landscape has a tripartite treaty between Rwanda, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo |

|

Private governance |

Conservation areas run by: ● Individual landowners ● Non-profit organizations (e.g., NGOs, universities, etc.) ● For-profit organizations (e.g., corporate landowners) |

● Malilangwe Trust in Zimbabwe is privately owned and governed ● Ol Pejeta Conservancy, Kenya, is governed by a private company ● Mpala Conservancy, Kenya is governed by a non-profit board |

|

Governance by indigenous peoples and local communities |

● Conserved territories and areas established and run by indigenous peoples ● Community conservation areas and territories established and run by local communities |

● Kenya: Imbirikani and Kuku Group Ranch, Il Ngwesi and Westgate community conservancies ● Tanzania: Enduimet and Burunge wildlife management areas, community-governed ● Namibia: ≠Khoadi-//Hoas Conservancy and Torra conservancies governed by community |

Source: Borrini-Feyerabend et al. 2013.

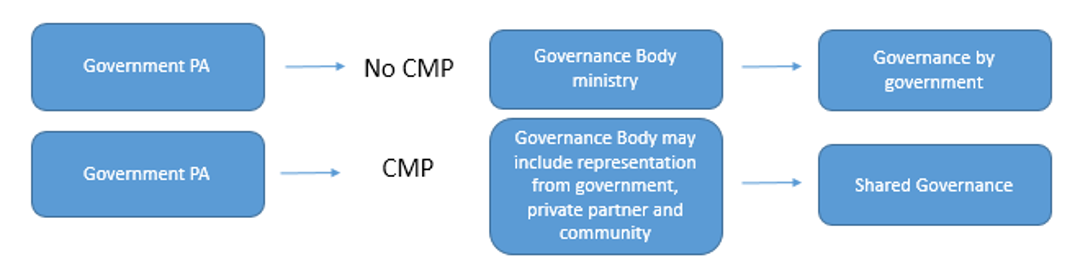

A national government’s engagement in a CMP with a partner may shift the governance model from governance by government to shared governance, i.e., the creation of a board that oversees the governance of a PA and includes government representation as well as representation from the private partner (see Figure 3.2). In some CMPs, the board includes representation from IPLCs. For example, there is community representation in four CMP governance bodies in Central and West Africa in Odzala-Kokoua, Nouabalé-Ndoki (see case study in Appendix E), Pendjari, and Termit and Tin Toumma (Brugière 2020). In many PAs, IPLCs are legitimate and relevant stakeholders and should be involved in the PA governance by having a seat on the board or participating in the advisory committee.

Figure 3.2 - Potential Shift in Governance with the Adoption of an Integrated or Delegated CMP

Source: World Bank. Original figure for this publication.

3.2 - Description of CMP models

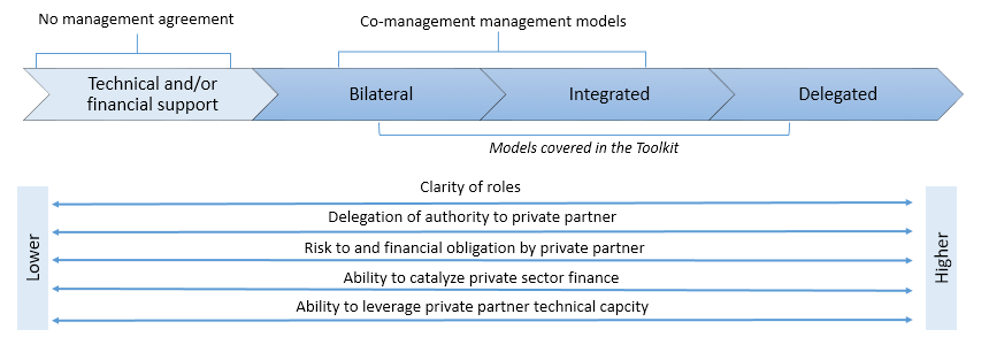

There are three primary CMP models in Africa, one of which, co-management, is further differentiated into two sub-categories (Baghai et al. 2018; Baghai 2016; Lindsey et al. 2021).

Financial and technical support , where the state retains full governance authority and the private partner provides technical and financial support (usually no management agreement).

Co-management CMPs , in which the state and the partner collaborate. This is further differentiated as follows:

a. Bilateral CMPs, in which the state and the partner agree to collaborate on PA management, with the two entities and their structures working side-by-side in the PA under a management agreement.

b. Integrated CMPs, in which the state and the partner agree to collaborate on PA management through a management agreement and create an SPV to undertake management, with equal representation by the parties on the SPV board.

Delegated CMPs , which are similar to integrated CMPs but have the majority of the SPV board appointed by the private partner.

The Toolkit focuses on co-management and delegated CMP models because of growing interest in them. The provision of technical and financial support by a partner to a PA authority is the traditional model of conservation support, which involves the partner implementing projects or providing financial support or advice to the PA authority without, in most cases, a formal management agreement. There are some very successful financial and technical support models. For example, the FZS has had a successful long-term partnership with the DNPW in Zambia for management of North Luangwa NP and with the Tanzania National Parks Authority for the management of the Serengeti NP. However, there are shortcomings in the financial and technical support model that have been extensively documented, such as start-and-stop funding and the lack of long-term project support and accountability. This is partially fueling the interest in co-management and delegated management models.

Bilateral, integrated, and delegated CMPs involve a formal management contract in which the public partner devolves certain levels of management responsibilities to the partner. In many cases, the adoption of a formal CMP is preceded by the partner providing financial and technical support to the PA authority. While not a necessary factor for entering into a CMP, such prior engagement can help the partner understand the challenges in the PA, PA authority capacity needs, conservation targets, and potential solutions. The prior engagement also helps the PA authority understand how the partner works and develop a relationship and build trust, which is fundamental for the success of the CMP. Table 3.3 describes bilateral, integrated, and delegated CMPs, and Appendix E includes a further description of each model.

Prior to signing an integrated CMP in Gonarezhou NP, Zimbabwe, FZS provided technical and financial support for nine years to the ZPWMA (see Appendix D, Figure D.4). The African Wildlife Foundation (AWF) provided three years of support to the Ethiopia Wildlife and Conservation Authority (EWCA) in Simien Mountains NP in Ethiopia prior to signing a bilateral CMP (see Appendix D, Figure D.8).

Table 3.3 - Collaborative Management Models, Governance, Management, and Examples

|

Categories |

Co-management Models |

|

|

|

Bilateral CMP |

Integrated CMP |

Delegated CMP |

|

|

Structure |

Partners maintain independent structure |

SPV created, forming one entity |

SPV created forming one entity |

|

Governance |

State leads strategy and oversight with involvement and in some cases, consensus of the partner on certain project-related issues; joint steering committee might appoint project leadership in the PA |

Partner shares governance responsibility with the state. Generally, a joint entity and SPV (e.g., foundation, non-profit company) is created in the host country. Shares are split evenly between the partner and government. Strategy and oversight managed by the SPV board |

Partner shares governance responsibility with the state. Generally, a joint entity and SPV (e.g., foundation, non-profit company) is created in the host country. Partner has most of the seats on the board. Strategy and oversight managed by SPV |

|

Management |

PA authority has management authority but allocates certain management aspects to the partner. For example, the PA authority oversees management of law enforcement and management of PA staff and shares authority with the partner for project-related decisions such as ecological monitoring and tourism development |

Management delegated to the SPV and shared to varying degrees between the state and NGO; often includes secondment of law enforcement manager by the government; all staff managed by the SPV, under leadership of the partner, with some government staff seconded

Secondment is defined as when an employee is temporarily transferred to another department or organization for a temporary assignment |

Management is delegated to the SPV. Partner appoints PA manager; often includes secondment of law enforcement manager by the government; all staff managed by the SPV, under leadership of the partner |

|

Examples |

● AWF and ICCN, Bili Uele, Democratic Republic of Congo ● African Nature Investors Foundation and the Nigerian NP Service, Gashaka Gumti, Nigeria |

● FZS and ZPWMA, Gonarezhou NP, Zimbabwe ● Carr Foundation and government of Mozambique, Gorongosa, Mozambique |

● African Parks and DNPW, Liuwa Plains, Zambia ● WCS and ICCN, Nouabale-Ndoki NP, Democratic Republic of Congo |

Source: Adapted from Baghai et al. 2018; Baghai 2016.

Each CMP model involves different levels of risk, responsibility, and obligations, outlined in Figure 3.3. Both partners should consider all aspects of the CMP and their ability and willingness to take on this commitment.

Figure 3.3 - Risk and Obligation Associated with CMP Models

Source: Adapted from WBG 2020b.

3.3 - Strengths and Weaknesses of Different CMP Models

PAs in Africa are diverse, face a range of threats, and have distinctive needs. Governments and the respective partners should understand the different CMP models and the strengths and weaknesses of each, and determine the most appropriate model for the PA authority and the PA under consideration.

Table 3.4 - CMP Models: Strengths and Weaknesses

|

CMP Model |

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

|

|

Co-management |

Bilateral |

Legitimacy of the PA authority’s involvement in management of a state PA; maintaining government responsibility |

Parallel structures, policies, and procedures in human resources and finance can create frustration, division, financial inefficiency, and tension |

|

|

Capitalize on strengths of each partner — contextual political understanding with international capacity and best practices |

Potential for conflict, especially with two leaders on the ground if their relationship breaks down |

|

|

|

|

Lack of clear accountability and roles and responsibilities if not clearly outlined in the agreement, leading to conflict |

|

|

|

|

Diffuse responsibility can lead to a lack of accountability |

|

|

|

|

Potential for political interference |

|

|

|

|

Potential for mistrust if there is not sufficient transparency |

|

|

Integrated |

All staff employed by the SPV, subject to the same conditions of employment and same rules and regulations, with clear reporting lines |

Political risk/public distrust from high level of independence of private partner. Tensions may result from lack of understanding of the partnership and misperceptions |

|

|

|

Innovation, flexibility, and decision-making culture of private sector combined with PA authority experience, knowledge of the PA |

Potential for conflict and misunderstanding between two entities and work cultures, requiring a leader who can help bridge these |

|

|

|

High level of autonomy at PA level allows quick decision-making |

Managing expectations from local communities and other relevant stakeholders |

|

|

|

Delegated |

Partner has a very clear mandate that allows for quick decision-making and full accountability |

Limited reach because governments are reluctant to delegate to partners, especially flagship PAs that produce revenue for government |

|

|

|

Partnership at governance level ensures government participation in strategy and oversight, lends itself to transparency |

Concern of “foreign entities” taking over national PAs and compromising state sovereignty |

|

|

|

All staff employed by SPV, subject to same conditions of employment, same rules and regulations, and clear reporting lines |

Might be perceived as incapacitating the PA authority |

|

|

|

Innovation, flexibility, and decision-making culture of private sector |

Potential resentment by PA authority, which doesn’t have the resources to fulfill mandate, could result in reluctance to cooperate |

|

|

|

|

Managing expectations from local communities and other relevant stakeholders |

Source: Adapted from Baghai et al. 2018; Baghai et al. 2018b; Brugière 2020.

Researchers found that delegated management and integrated management CMPs have delivered more clear conservation outcomes than bilateral CMPs. Key reasons include: improved governance and oversight structures; the ability to manage the PA independently; autonomy and insulation from political interference; long-term commitments; the ability to build strong teams by attracting skilled staff via transparent, meritocratic selection procedures and more flexibility to discipline or dismiss underperforming personnel; and increased accountability (Baghai et al. 2018; Lindsey et al. 2021).

3.4 - Case Studies of the Three CMP Models

Appendix D includes nine case studies from nine countries. Below are three examples of CMPs from three countries with three private partners, covering the three CMP models.

Table 3.5 - CMP Model Case Studies

|

Category |

Bilateral CMP |

Integrated CMP |

Delegated CMP |

|

Protected area |

Simien Mountains NP |

Gorongosa NP |

Akagera NP |

|

Size km2 |

220 |

3,200 |

1,122 |

|

Country |

Ethiopia |

Mozambique |

Rwanda |

|

Government partner |

Ethiopia Wildlife Conservation Authority |

Government of Mozambique |

Rwanda Development Board |

|

Private partner |

African Wildlife Foundation |

Gorongosa Project |

African Parks |

|

Year contract signed |

2017 (update of 2014 agreement) |

2016 (update of 2008 agreement) |

2010 |

|

Duration of negotiation |

5 Years |

4 Years |

3 Years |

|

Contract duration |

15 Years |

25 Years |

20 Years |

|

Partner engaged in PA prior to contract |

Yes, since 2012 |

Yes, since 2008 |

No |

|

Revenue retention (see note) |

No. All revenue to national government accounts |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Number of staff |

AWF and EWCA manage own staff separately |

700 permanent, 400 seasonal, 85 percent local |

271, up from 18 in 2010, 99 percent Rwandan |

|

Governance |

Ultimate authority with EWCA. Project coordination unit (PCU) comprised of one EWCA representative; one AWF representative; one KfW representative |

Oversight committee composed of one government representative and one Gorongosa Project representative |

Board of trustees includes seven trustees: three appointed by government; four appointed by African Parks |

|

Ecological success |

● Removed from the World Heritage Site in Danger list ● Livestock grazing in the park reduced by 43 percent ● Ethiopian wolf increased from 55 in 2013 to 75 by 2021 ● Walia ibex population increased from 585 in 2018 to 695 in 2021 |

● Poaching reduced by 70 percent ● Animal population increased from 15,000 in 2008 to 90,000 in 2020 ● 781 elephant, 815 wildebeest, 766 hippo, and 1,221 buffalo (2020), up from 2000 populations of less than 200 elephant, 20 wildebeest, 100 hippo and 100 buffalo |

● Wildlife increase: 5,000 in 2010 to 13,500 in 2019 ● 23 eastern black rhinoceros reintroduced. 2020: population of 27 ● Lions reintroduced. 2020: population of 40 ● Wildlife numbers: From 4,476 in 2010 to 13,442 in 2019 |

|

Economic success |

● Annual operating budget increased from $100,000 to $1 million |

● $85 million invested, $13.7 million annual budget ● Ecotourism revenue: $737,132 from Jan-Sept 2019, compared to a baseline of zero |

● Budget $3.25 million in 2019 ● Revenue: $203,063 in 2010, $2.6 million in 2019 ● Average spend per person: $16 in 2010, $46 in 2019 ● Luxury private sector tourism partners, such as Wilderness Safaris |

|

Social success |

● Modern primary school developed, supporting 363 students ● 1,000 schoolchildren visit the park annually ● COVID emergency cash for work program 2020: 6,405 individual laborers, affecting 1,601 households |

● Human development budget $1.78 million in 2019 ● More than 150,000 people treated per year by medical services ● 500 local families engaged in coffee business, with 200 jobs ● 2019 agricultural extension services reached 10,000 farmers |

● Total community benefit was zero dollars in 2010, $728,435 in 2019 ● More than 2,000 school children visit ANP annually for free with teachers and local leaders |

Source: African Parks, AWF, Gorongosa, and RDB staff and websites (see Appendix D, Figures D.3, D.4, D.8).African Parks, AWF, Gorongosa, and RDB staff and websites (see Appendix D, Figures D.3, D.4, D.8).

Note: Revenue retention at the PA level, in many cases, includes a percentage of revenue that supports the PA authority. Most PA authorities support non-functional PAs with revenue from functional PAs; therefore, this needs to be considered when developing a revenue model for the CMP. The amount that goes to the PA authority may increase after the initial development and stabilization period, which varies depending on the PA. The CMP contract will stipulate in the event of a surplus, the percentage that goes to the PA authority to create a net benefit for the entire PA estate. In other cases, such as Akagera NP, the government of Rwanda provides funding to the CMP budget annually—rather than taking it out in the form of revenues. This is very attractive to donors.

3.5 - CMP Best Practice Principles for Success

When developing, managing, and ending a CMP, governments and partners should consider a number of best practice principles that were developed from experiences of government and NGO practitioners (see Table 3.6). These 24 principles are organized under six pillars: CMP Development; Nature of the Partnership; Governance; Administration; Operations; and Finance (adapted from Baghai et al. 2018; Conservation Capital 2017; Lindsey et al. 2020; consultation with CMP partners). Appendix F includes further description of these principles and Appendix P includes key aspects of each of these principles that should be included in a CMP contract.

Table 3.6 - The Six Pillars and 24 Principles for Successful CMPs

|

1. CMP Development |

2. Nature of the Partnership |

|

a. Attract a Qualified Partner |

e. Trust Between Partners |

|

● Confirm Adequate Funding and Capacity to Generate Finance |

f. Buy-in at All Levels |

|

c. Develop the Contract Together |

g. Common Goals and Objectives |

|

d. Clarify Roles and Responsibility |

h. Respect Environmental and Social Standards |

|

3. Governance |

4. Administration |

|

i. Provide Adequate Duration and Outline Succession |

m. Unify Staffing |

|

j. Ensure Equitable Representation |

n. Determine Management Leadership |

|

k. Communicate the Partnership |

o. Align Policies and Procedures |

|

l. Mitigate Risk |

p. Pre-plan Closure/Termination |

|

5. Operations |

6. Finance |

|

q. Develop Work Plans Together |

v. Build Towards Sustainability |

|

r. Legitimize the Management Framework |

w. Drive Enterprise Development |

|

s. Respect the Mandate of Law Enforcement |

x. Manage Surplus/Deficit |

|

t. Effectively Engage Stakeholder Communities |

|

|

u. Respect Transboundary Responsibility |

|

Source: Conservation Capital 2017.

CMP Development

- Attract a Qualified Partner: The selection of a qualified partner with the requisite skills and experience is fundamental to the success of a CMP. Sections 5.5 and 5.7 outline a process for vetting and selecting a qualified partner.

- Confirm Adequate Funding and Capacity to Generate Finance: The ability to financially execute a management agreement is fundamental to its success. As part of the partner selection process outlined in Chapter 5, there should be due diligence and verification of start-up capital sufficient to address the needs of the PA and of the ability of the partner to develop long-term viable revenue models.

- Develop Contracts Together: Contracts should follow best practice and be developed collectively to foster collaboration, develop joint ownership, and avoid confusion over content.

- Clarify Roles and Responsibilities: CMP agreements must be explicitly clear about roles, responsibility, reporting lines, and accountability to avoid confusion and conflict (Appendix P includes a description of roles and responsibilities to include in the CMP contract).

- Trust Between Partners: CMPs can have solid contracts, suitable funding, and a highly experienced partner. However, they will not work without trust between the partners. While a difficult parameter to measure, building trust is something both parties should consider when developing a CMP. No formula exists for such vital trust-building. If the private partner is supporting the PA authority prior to the CMP through financial and technical support, the engagement is a good opportunity to develop trust. However, not all partners work in a PA prior to entering into a CMP, and it is not necessary for success.

- Buy-in at All Levels: Transparency about the CMP development process is critical to ensuring buy-in at all levels. A CMP driven from the top (ministry or even higher) without buy-in at local level risks operational challenges. Likewise, a CMP driven from the PA level or by a donor without legitimate buy-in from PA authority HQ risks political meddling.

- Common Goals and Objectives: Both parties need to be moving toward the same objectives and goals. The partners should discuss a shared vision, and these aspects should be documented in the management agreement as well as the general management plan.

- Respect Environmental and Social Standards (ESS): ESS are a set of policies, guidelines and operational procedures designed to first identify and then, following the standard mitigation hierarchy, try to avoid, minimize, mitigate, and compensate when necessary adverse environmental and social impacts that may arise in the implementation of a project. The partners should jointly agree on a comprehensive framework that enables staff and project developers and managers to comply with ESS (see Chapter 6).

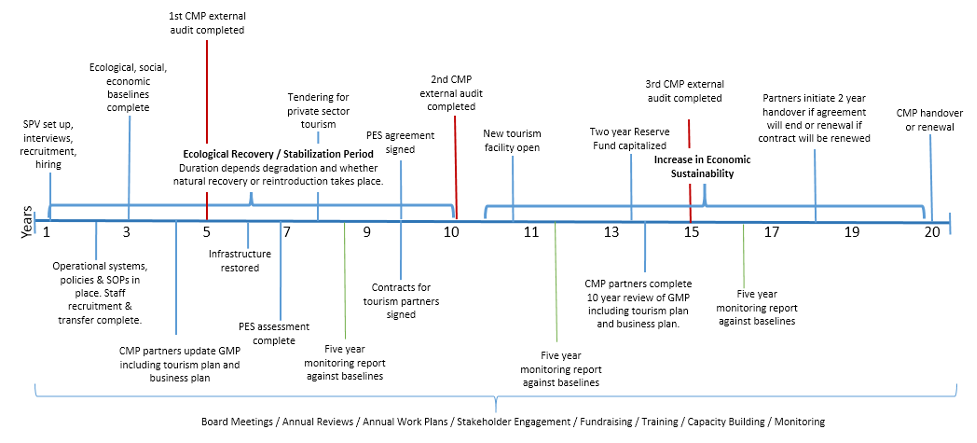

- Provide Adequate Duration and Outlining Succession: The duration of the CMP depends on the PA and the PA authority goals. A CMP can be used as an interim (15-20 year) tool or longer-term, and in some cases, a more permanent solution. The duration is decided by the government for national PAs, and intentions should be explicit in the beginning of the partnership to avoid confusion and to ensure proper planning. In general, 15 to 20 years is recommended as a minimum. This provides adequate time to attract funding and investment, create standard operating procedures (SOPs), stabilize operations, and transition management at the end of the agreement. Figure 3.4 is a hypothetical timeline for a CMP in a PA that is highly degraded. Shorter timeframes, while desirable from some governments, do not provide the duration to establish policies, procedures, steady funding, enterprises, capacity, and overall recovery. If the intention of both parties, as defined in the CMP, is for the CMP to be used as an interim tool, succession planning and how skills will be transferred should be adequately planned.

Figure 3.4 - Sample Timeline for a 20-year CMP for a PA that Requires Significant Ecological Recovery

Source: World Bank. Original figure for this publication.

Note: Timelines will vary depending on context; this is an example, not a guide.

- Ensure Equitable Representation: No one party wishes to be dominated or feel dominated by the other. There are several ways, beyond representation on the board or committee, to avoid this (see Appendix F).

- Communicate the Partnership: Both parties are responsible for communicating, internally and externally, about the CMP before and throughout the life of the project. This includes communication across national, local, and regional governments, local communities, and traditional authorities. Communication between the private partner and the PA authority is critical to success and cannot be limited to formal structures (Brugière 2020).

- Mitigate Risk: Minimizing inappropriate risk and liability is critical for a CMP and the individuals involved. The partner should complete a risk analysis and mitigation plan, which should be updated and maintained throughout the life of the CMP.

d. Unify Staffing: The ideal CMP should form and represent one unified structure of staffing to create efficiencies, clarify management responsibility, and make standards uniform. In the case of a bilateral CMP, the partners should work to mirror standards, procedures, and policies to the extent feasible and clearly outline roles and responsibilities to avoid confusion.

e. Determine Management Leadership: The caliber of executive leadership is often the deciding factor of the success of a CMP. The board should be responsible for appointing the senior executive positions from nominated employees from each party under secondment or through direct recruitment. Best practice recommends that the senior position responsible for law enforcement be seconded from the state PA authority.

f. Align Policies and Procedures: Senior management will be required to develop policies and procedures related to, among others, human resources, finance, and procurement. To ensure harmonization (and as an important feature for future succession), these policies and procedures should be adapted from government policies and procedures, to the extent feasible, without adopting or incorporating aspects that contribute to operational challenges.

g. Pre-plan Closure/Termination: The parties must pre-agree on a clear and thorough procedure for the closing out of the CMP in the event of completion, breach, or early termination, to deal with staff, assets, monies, liabilities, and ongoing third-party agreements (Appendix P includes details of each of these aspects).

h. Develop Work Plans Together: Developing the work plan together is efficient, draws on the expertise of each party, and creates a sense of ownership by both parties. Partners should develop an annual schedule that includes the review of the prior year’s achievements against the work plan and the development of the subsequent year’s work plan.

i. Legitimize the Management Framework: A CMP must be set within the legal framework of the host country. A general management plan (GMP) and related business plan provide a management framework. A GMP is established under PA and wildlife conservation law as the required and accepted instrument to frame the management and development of a PA and to implement relevant government policy. In some places, GMPs take years to develop and attain approval. In those cases, a rolling five-year business or management plan may be preferable.

j. Respect the Mandate of Law Enforcement: Law enforcement and security is a function of the state, and this dynamic must be respected within a CMP. Law enforcement undertaken by the private partner without legal authorization can pose serious liability for the private partner and risks serious misinterpretation around the private partner’s role.

k. Effectively Engage Stakeholder Communities: Local communities are almost always primary stakeholders and beneficiaries of a PA. Engagement with local communities cannot be separated from the PA management. Proper stakeholder engagement and consultation should take place throughout the life of the CMP.

- Respect Transboundary Responsibility: When a PA is part of a trans-frontier conservation area (TFCA), engagement with international neighbors and their PA authority is a sovereign matter. Therefore, the state authority should be the lead agency in international communication, while keeping the private partner abreast of TFCA matters.

Finance

- Build Towards Sustainability: While very few PAs are completely self-financing, striving for financial sustainability of a PA is a key objective of a CMP. Building the commercial basis toward financial sustainability for the PA also will help stimulate the local and national economy, creating incentives that make a PA socially and politically relevant.

- Drive Enterprise Development: Linked to the preceding principle, the CMP must be central to driving enterprise development within the PA and be given the requisite mandate and authority to promote and develop such conservation enterprise.

- Manage Surplus/Deficit : The CMP partners need a clear understanding of their obligations and rights from the outset of the agreement in the event of operating surpluses and deficits.

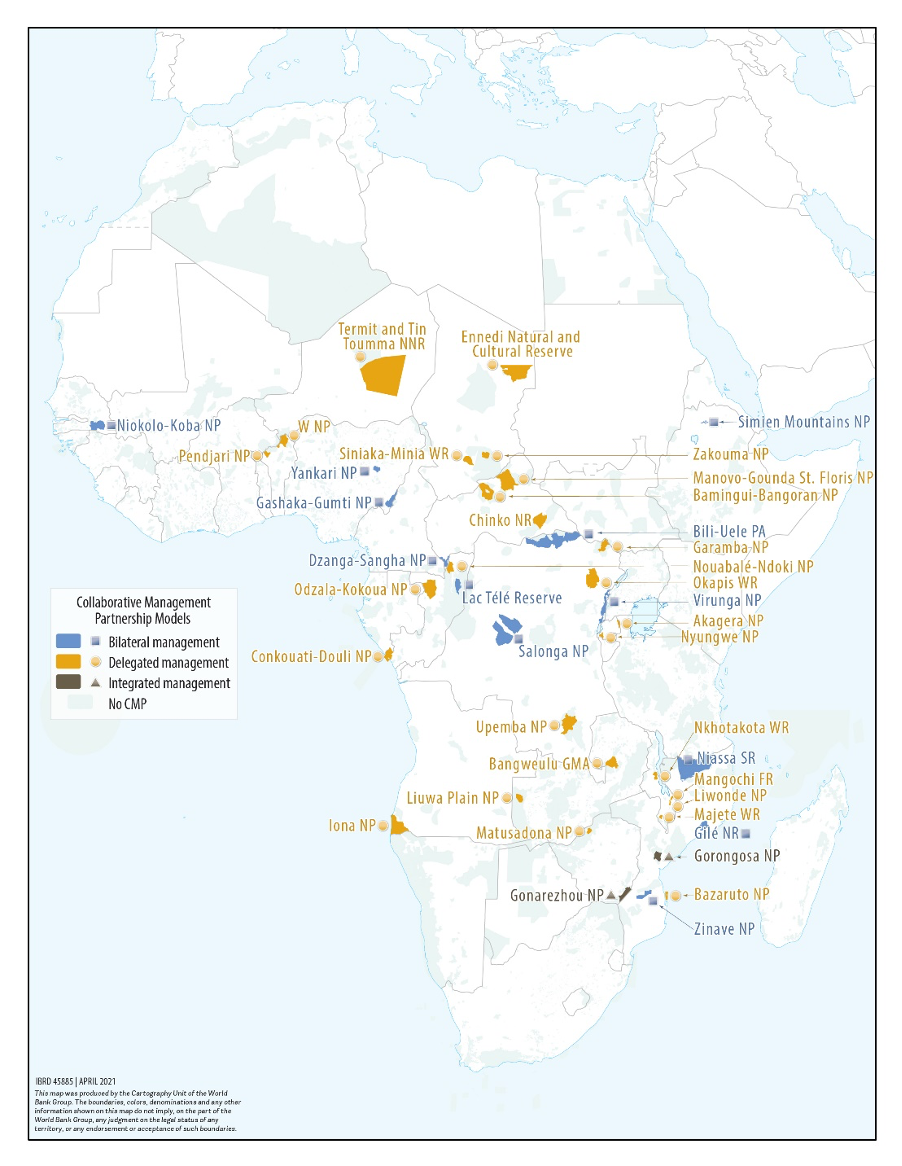

3.6 - Status of CMPs in Africa

Given the growing interest in co-management (bilateral and integrated) and delegated CMPs, the Toolkit focused on these models. While CMPs may include management by private sector partners, the majority of CMPs in Africa are managed by NGOs; therefore, the Toolkit focuses on CMPs with NGOs. There are 40 co-management and delegated CMPs in 15 countries in Africa, with 13 NGO partners (see Tables 3.7-3.9 and Map 3.1). This data does not include Madagascar, which has more than 20 different delegated management entities for national PAs, including national and international NGOs, as well as research organizations (Brugière 2020). Appendix G includes a description of the Madagascar management models. South Africa does not have any CMPs managed with NGOs. They have CMPs managed between PA authorities and communities, which are referred to as contractual parks and described in Appendix H. Appendix D, Figure D.7 includes a case study about a contractual park between the Makuleke Community and SANParks.

Africa supports approximately 8,601 terrestrial and marine PAs covering 4.2 million km2 and approximately 14 percent of the continent’s land area (30,000,000 km2). The area under CMP management represents approximately 11.5 percent of the total terrestrial PA estate.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, none of the 40 CMPs profiled in the Toolkit collapsed or had to reduce staff or cut salaries. Three delegated CMPs were signed during COVID-19, with a number in the pipeline.

Table 3.7 - Bilateral, Integrated, and Delegated CMP List by Country in Africa

|

No |

Country |

Number of Co-management and Delegated CMPs |

Number of NGO CMP Partners in Each Country |

|

|

|

1 |

Democratic Republic of Congo |

8 |

6 |

|

|

|

2 |

Mozambique |

5 |

5 |

|

|

|

3 |

Malawi |

4 |

1 |

|

|

|

4 |

Central African Republic |

3 |

2 |

|

|

|

5 |

Chad |

3 |

1 |

|

|

|

6 |

Republic of Congo |

3 |

2 |

|

|

|

7 |

Benin |

2 |

1 |

|

|

|

8 |

Nigeria |

2 |

2 |

|

|

|

9 |

Rwanda |

2 |

1 |

|

|

|

10 |

Zambia |

2 |

1 |

|

|

|

11 |

Zimbabwe |

2 |

2 |

|

|

|

12 |

Angola |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

13 |

Ethiopia |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

14 |

Niger |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

15 |

Senegal |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

Total CMPs |

40 |

||||

Source: Updated from Baghai et al. 2018; Baghai 2016; Brugière 2020; NGO and PA authority websites; and communication with CMP NGO and PA authority partners.

CMPs provide substantial support for national PA budgets. For example, 50 percent of Rwanda’s NPs are under CMPs, encompassing 92 percent of the national park estate in terms of size, which significantly offsets the RDB’s management budget. In Zimbabwe, the ZPWMA has CMPs with partners in two NPs — in Matusadona with African Parks and in Gonarezhou with FZS — which represents about a quarter of the NP estate. The ZPWMA has an annual budget deficit for NP management. These CMPs substantially offset costs.

The PAs under CMP include some of Africa’s most ecologically significant, iconic, and economically valuable conservation areas.

African Parks manages the Benin section of Parc W, West Africa’s largest PA, via a management partnership with the government of Benin. Parc W safeguards key species for the region.

WCS manages Nouabalé-Ndoki NP (see Appendix D, Figure 5) in partnership with the government of the Republic of Congo. WWF manages Salonga National Park in partnership with ICCN. The parks represent some of the best examples of an intact forest ecosystem remaining in the Congo Basin.

The Virunga Foundation manages

Virunga NPin partnership with ICCN. This is the only park in the world that supports three species of great apes.

Table 3.8 - Status of Co-management and Delegated CMPs in Africa

|

Active CM and DM CMPs |

40 |

|

Countries with CMPs |

15 |

|

Number of partners |

13 |

|

Shortest CMP |

5 Years |

|

Longest CMP |

50 Years |

|

Earliest CMP signed |

1985 |

|

CMP signed between 2015-2021 |

73 percent |

|

Total PA area in Africa km2 |

4.2 million |

|

Km2 with CMPs |

490,264 |

|

% PA area under CMPs |

11.5 percent |

Source: Updated from Baghai et al. 2018; Baghai 2016; Brugière 2020; NGO and PA authority websites; and communication with CMP NGO and PA authority partners.

The first CMP in Africa was in 1985 in the Fazao-Malkafassa NP in Togo (Brugière 2020). A substantial number of CMPs (73 percent) have been signed between 2015-2021, due to the demonstrated success of some of the earlier CMPs and increased government and donor interest in CMPs. Some contracts executed during this period were updated, extended, or improved existing contracts, or represented the graduation from a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to a more formal agreement. In many cases, updated contracts were due to lessons learned from earlier CMPs. For example, NGOs and government partners may better understand key factors for success, such as a clarity of roles and responsibilities, and the updated agreement incorporates these improvements. In addition, some of the earlier contracts were entered into urgently due to poaching and other illegal encroachment (Brugière 2020). The updated and revised versions incorporate lessons learned.

Table 3.9 - CMP List by NGO in Africa

There are 40 co-management and delegated management CMPs between government partners and NGOs in 15 countries in Africa with 13 NGO partners, excluding Madagascar and South Africa.

DM=delegated CMP; ICM=integrated CMP; and BM=bilateral CMP.

|

No. |

NGO |

Protected Area |

Country |

Model |

Size (km2) |

CMP Signed* |

|

1 |

African Parks |

Akagera NP |

Rwanda |

DM |

1,122 |

2010 |

|

2 |

African Parks |

Bangweulu Game Management Area |

Zambia |

DM |

6,000 |

2008 |

|

3 |

African Parks |

Bazaruto Archipelago NP |

Mozambique |

DM |

1,430 |

2017 |

|

4 |

African Parks |

Chinko Reserve |

Central African Republic |

DM |

59,000 |

2014 |

|

5 |

African Parks |

Ennedi Natural & Cultural Reserve |

Chad |

DM |

50,000 |

2017 |

|

6 |

African Parks |

Garamba NP |

Congo, Dem. Rep. |

DM |

5,133 |

2005 |

|

7 |

African Parks |

Iona NP |

Angola |

DM |

15,000 |

2019 |

|

8 |

African Parks |

Liuwa Plain NP |

Zambia |

DM |

3,369 |

2003 |

|

9 |

African Parks |

Liwonde NP |

Malawi |

DM |

548 |

2015 |

|

10 |

African Parks |

Majete Wildlife Reserve |

Malawi |

DM |

700 |

2003 |

|

11 |

African Parks |

Mangochi Forest Reserve |

Malawi |

DM |

407 |

2018 |

|

12 |

African Parks |

Matusadona NP |

Zimbabwe |

DM |

1,470 |

2019 |

|

13 |

African Parks |

Nkhotakota Wildlife Reserve |

Malawi |

DM |

1,800 |

2015 |

|

14 |

African Parks |

Nyungwe NP |

Rwanda |

DM |

970 |

2020 |

|

15 |

African Parks |

Odzala-Kokoua NP |

Congo, Rep. |

DM |

13,500 |

2010 |

|

16 |

African Parks |

Pendjari NP |

Benin |

DM |

2,755 |

2017 |

|

17 |

African Parks |

Siniaka Minia Wildlife Reserve |

Chad |

DM |

4,260 |

2017 |

|

18 |

African Parks |

W NP |

Benin |

DM |

8,000 |

2020 |

|

19 |

African Parks |

Zakouma NP |

Chad |

DM |

3,000 |

2010 |

|

20 |

ANI |

Gashaka Gumti NP |

Nigeria |

BCM |

6,402 |

2018 |

|

21 |

AWF |

Bili-Uele PA |

Congo, Dem. Rep. |

BCM |

32,748 |

2016 |

|

22 |

AWF |

Simien Mountain NP |

Ethiopia |

BCM |

220 |

2017 |

|

23 |

Carr Foundation |

Gorongosa NP |

Mozambique |

ICM |

3,770 |

2008 |

|

24 |

Forgotten Parks Foundation |

Upemba NP |

Congo, Dem. Rep. |

DM |

11,730 |

2017 |

|

25 |

FZS |

Gonarezhou NP |

Zimbabwe |

ICM |

5,053 |

2017 |

|

26 |

IGF Foundation |

Gile National Reserve |

Mozambique |

BCM |

2,860 |

2018 |

|

27 |

Noé |

Termit and Tin Toumma National Nature Reserve |

Niger |

DM |

90,507 |

2018 |

|

28 |

Noé |

Conkouati Douli NP |

Congo, Rep. |

DM |

5,000 |

2021 |

|

29 |

Panthera |

Niokolo Koba NP |

Senegal |

BCM |

9,130 |

2019 |

|

30 |

PPF |

Zinave NP |

Mozambique |

BCM |

4,000 |

2015 |

|

31 |

Virunga Foundation |

Virunga NP |

Congo, Dem. Rep. |

BCM |

7,769 |

2015 |

|

32 |

WCS |

Nouabale-Ndoki NP |

Congo, Rep. |

DM |

3,922 |

2014 |

|

33 |

WCS |

Okapi Wildlife Reserve |

Congo, Dem. Rep. |

DM |

13,726 |

2019 |

|

34 |

WCS |

Niassa National Reserve |

Mozambique |

BCM |

42,000 |

2019 |

|

35 |

WCS |

Yankari NP |

Nigeria |

BCM |

2,250 |

2014 |

|

36 |

WCS |

Manovo-Gounda St. Floris NP |

Central African Republic |

DM |

17400 |

2018 |

|

37 |

WCS |

Lac Télé Community Reserve** |

Congo, Rep. |

DM |

4,389 |

2018 |

|

38 |

WCS |

Bamingui-Bangoran NP |

Central African Republic |

DM |

11,191 |

2018 |

|

39 |

WWF |

Salonga NP |

Congo, Dem. Rep. |

BCM |

36,000 |

2015 |

|

40 |

WWF |

Dzanga-Sangha NP |

Congo, Dem. Rep. |

BCM |

6,866 |

2019 |

|

Total km2 under collaborative management partnerships |

490,264 |

|

||||

* The year referred to in Table 3.9 is the most recent CMP signed. In some cases, prior agreements were updated.

**Lac Tele is a state PA, despite its name as a Community Reserve.

Source: Updated from Baghai et al. 2018; Baghai 2016; Brugière 2020; NGO and PA authority websites; and communication with CMP NGO and PA authority partners.

Most CMPs (42 percent) are in Central Africa, followed by Southern Africa (35 percent) (see Figure 3.5). Despite challenges in PA management effectiveness in East Africa, there is a gap in the uptake of CMPs. This is partially due to a lack of an enabling environment in some countries and resistance to CMPs by governments.

Figure 3.5 - Regional CMP Distribution in Africa <<<-->>>> Figure 3.6 - Number of CMPs per Country

Source: Updated from Baghai et al. 2018; Baghai 2016; Brugière 2020; NGO and PA authority websites; and communication with CMP NGO and PA authority partners.

CMPs are in 15 countries in Africa (excluding Madagascar and South Africa). The Democratic Republic of Congo has the highest percentage of CMPs (20 percent) followed by Mozambique (12 percent) (see Figure 3.6). The Democratic Republic of Congo had some of the earliest CMPs, which were established in direct response to the elephant poaching crisis (Brugière 2020). Recognizing funding and capacity limitations, ICCN established CMPs to mitigate the threats and has continued to expand the CMP portfolio in the country, given the success of some of the early CMPs, the scale of the PA estate in the country, and the agency limitations. In Mozambique, the government recognized CMPs as a strategic approach to improve the management of CMPs and proactively sought partnerships in target PAs.

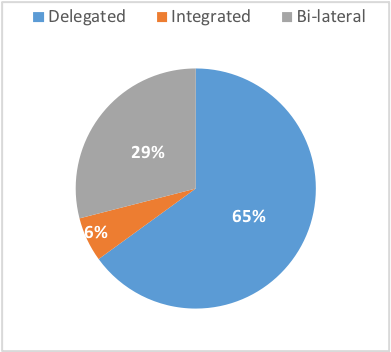

Nineteen of the 40 CMPs in Africa (48 percent) are in partnership with the NGO African Parks, which enters into partnerships using a delegated management approach. Most of the CMP models in Africa are delegated (73 percent) (see Figure 3.7). There is growing interest in the integrated management model because of its unifying structure and balanced partnership between the partner and the PAA. However, in many countries, creating an SPV and seconding state staff to this independent entity takes time. Therefore, some organizations start with a bilateral agreement and eventually transition to an integrated model.

Figure 3.7 - Share of Types of CMP Models Used in Africa

Source: Updated from Baghai et al. 2018; Baghai 2016; Brugière 2020; NGO and PA authority websites; and communication with CMP NGO and PA authority partners.

African Parks and WCS hold 26 of the 40 CMPs in Africa (see Table 3.10). Currently, there are more PAs available for partnerships than there are management partners. The barrier for partner engagement includes lack of management expertise, in particular CMP managers that have the requisite experience, and lack of adequate funding. African Parks has a program that supports smaller organizations in developing policies and procedures for CMPs, and mentors organizations in conservation management to help build capacity for partners. For example, African Parks supports Noé, a France-based organization that has CMPs in Niger and the Republic of Congo. Interestingly, Noé's CMP in Niger, at 90,507 km2, covers the same size area as WCS’s seven CMPs (see Table 3.10).

Table 3.10 - Number of CMPs and Area of Land Managed by CMP Partner

|

NGO Partner |

Number of CMPs |

Total km2 Managed |

Percentage of Total CMP km2 Managed |

|

|

African Parks |

19 |

173,331 |

35.4 |

|

|

WCS |

7 |

94,878 |

19.4 |

|

|

AWF |

2 |

32,968 |

6.7 |

|

|

Noé |

2 |

95,507 |

19.5 |

|

|

WWF |

2 |

42,866 |

8.7 |

|

|

ANI |

1 |

6,402 |

1.3 |

|

|

Carr Foundation |

1 |

3,770 |

0.8 |

|

|

Forgotten Parks Foundation |

1 |

11,730 |

2.4 |

|

|

FZS |

1 |

5,053 |

1.0 |

|

|

IGF Foundation |

1 |

2,860 |

0.6 |

|

|

Panthera |

1 |

9,130 |

1.9 |

|

|

Peace Parks Foundation |

1 |

4,000 |

0.8 |

|

|

Virunga Foundation |

1 |

7,769 |

1.6 |

|

Source: Updated from Baghai et al. 2018; Baghai 2016; Brugière 2020; NGO and PA authority websites; and communication with CMP NGO and PA authority partners.

Eight NGOs have only one CMP. Most partners are interested in either expanding the area under their CMP, such as the Carr Foundation in Mozambique for the Gorongosa landscape, or taking on more CMPs in different areas, such as FZS. All of the CMPs profiled in the Toolkit are with international NGOs, which creates some animosity in certain countries and contributes to the challenges of uptake by governments around delegated management in particular. There are governments keen to enter into CMPs; however, there are not enough NGOs with adequate capacity and financial means to meet the demand. Significant financial and technical support provided by local and national organizations presents an opportunity for their expanded engagement in bilateral, integrated, and delegated CMPs in the future. For example, in Zambia, Conservation Lower Zambezi has been supporting the government in management of Lower Zambezi NP. Mentorship programs with international NGOs, such as African Parks’ incubator program, should focus on national NGOs to build capacity in the country.

Map 3.1 - Bilateral, Integrated, and Delegated CMPs with NGOs in Africa

Source: Updated from Baghai et al. 2018; Baghai 2016; Brugière 2020; NGO and PA authority websites; and communication with CMP NGO and PA authority partners.

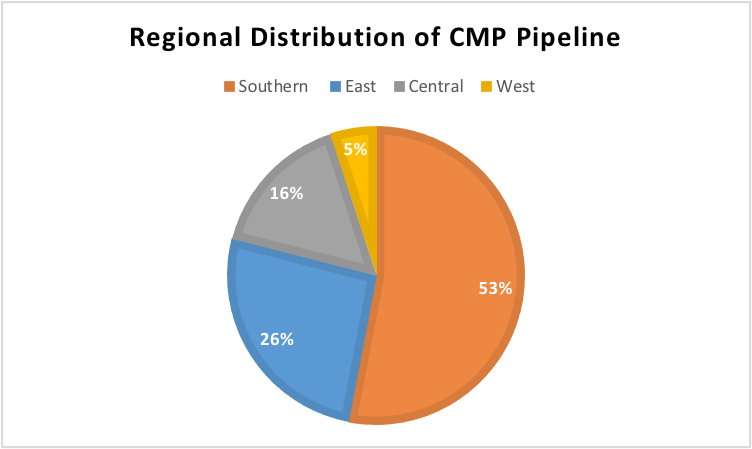

There are 19 CMPs known to the authors that are under development in 11 countries covering approximately 85,700 km2. These include CMPs that are under negotiation with NGOs or those intended for tendering. This includes South Africa and Madagascar but is not exhaustive as there are certain to be others unknown to the authors under development; however, it does indicate the significant interest in CMPs. The majority of the CMPs in the pipeline (53 percent) are in Southern Africa followed by 26 percent in East Africa. This shows a significant increase in CMPs in East Africa, which currently comprise 11.5 percent of the existing CMPs.

Figure 3.8 - Share of Pipeline of CMPs under Active Development

Source: World Bank consultation with NGO and PA authority partners.