Governments are ultimately responsible for the decision to enter into a CMP for state protected areas. There are five key steps that governments and other protected area managers can undertake to identify and screen CMP opportunities. This chapter describes these steps and provides a diversity of tools that to help identify PAs suitable for CMPs, and determine the most appropriate CMP model.

4.1 - Government Decision

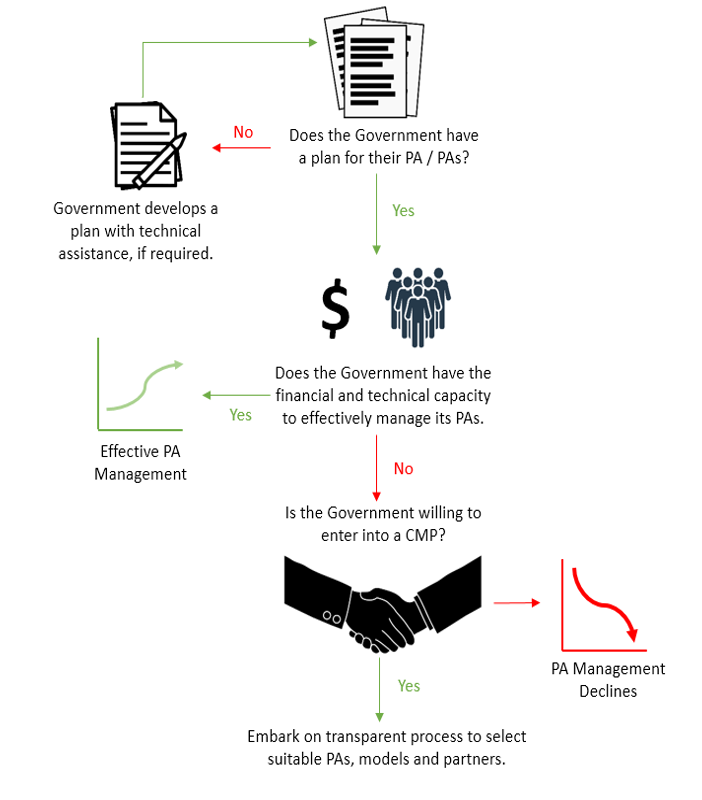

The decision to engage in a CMP for a national PA rests with the government. The process to determine whether to engage with a CMP starts with the PA authority strategy and an assessment of its ability to deliver on that strategy. If a PA authority determines that it is unable to achieve its goals without external management support and is willing to engage in a CMP, it would then embark on a process of selecting suitable PAs, selecting the appropriate CMP model for that particular PA, followed by the sourcing of a qualified partner (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 - Government Decision-Making Matrix Tool for CMPs

Source: Adapted from Lindsey et al. 2021.

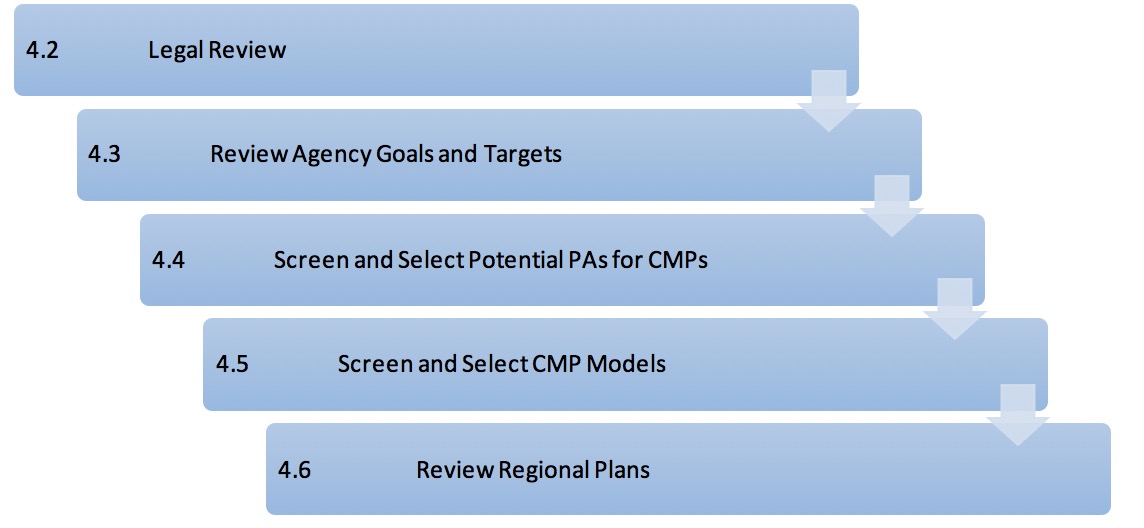

Following a government’s decision to consider CMPs for its PA estates, it would embark on a series of steps to determine the feasibility of CMPs in the country and the most suitable PA for consideration. The following section highlights these steps (see Figure 4.2), which mirror the PPP cycle outlined by the World Bank’s PPP Knowledge Lab.

Figure 4.2 - Five Steps to Identify and Screen CMP Opportunities

Source: Adapted from COMIFAC 2019; Lindsey et al. 2021; WBG 2020b.

4.2 - Legal Review

CMPs need to be developed within the legal framework of the host country. The contracting authority (CA) — which is the government entity that has the legal authority to enter a CMP and, in some cases, the entity tasked with overseeing the process, such as the PA agency or relevant ministry — should complete a legal review to determine the best way to set up CMPs and the related operational facets prior to embarking on the selection process. All legal aspects need to be vetted from attracting a partner and establishing the contract to fulfilling international treaties, but at an initial stage, the key legal focus should be on how to establish the CMP, taking into consideration how domestic laws apply and which international legislation needs to be considered.

Box 4.1 PPP Framework for CMPs in Kenya

In Kenya, the 2013 Wildlife Conservation and Management Act (WCMA) guides the establishment and management of national parks but does not include a reference for CMPs. Kenya has not established a CMP. The key government act relevant to the awarding of collaborative management rights over national parks is the PPP Act 2013, which designates a contracting authority (CA) to engage in collaborative management.

- A CA is defined as a state department, agency, state corporation, or county government, which intends to have function undertaken by it performed by a private party. With respect to national parks in Kenya, the relevant CA will be the Kenya Wildlife Service.

- Key components of the PPP Act are as follows:

o Section 19: Provides that the CA may enter into a PPP with a private party in accordance with the Second Schedule of the Act.

o Second Schedule: The Cabinet Secretary (National Treasury and Planning) is the key actor in providing for PPPs.

o Parts IV, V, VI, and VII: Provide for project identification and approval processes.

- General Principles: The PPP Act provides that the CA should:

iv. Conduct pre-qualification procedures, ensuring that the private company has:

▪ Financial capacity to undertake the project.

▪ Relevant experience in undertaking similar projects.

▪ Relevant expertise to undertake the project.

v. Undertake a competitive bidding process, guided by the principles of transparency, free and fair competition, and equal opportunity.

The private partner will want to refer to the WCMA, which outlines in section VII the international treaties, conventions, and agreements ratified by the government of Kenya, and in section VI discusses aspects pertaining to the protection of endangered and threatened species and ecosystems, as well as species recovery plans. In addition, the WCMA is the legal framework for the management of wildlife in the country. For example, WCMA (2013) Schedule Five outlines the requirements of GMPs and the planning framework (WBG 2020b).

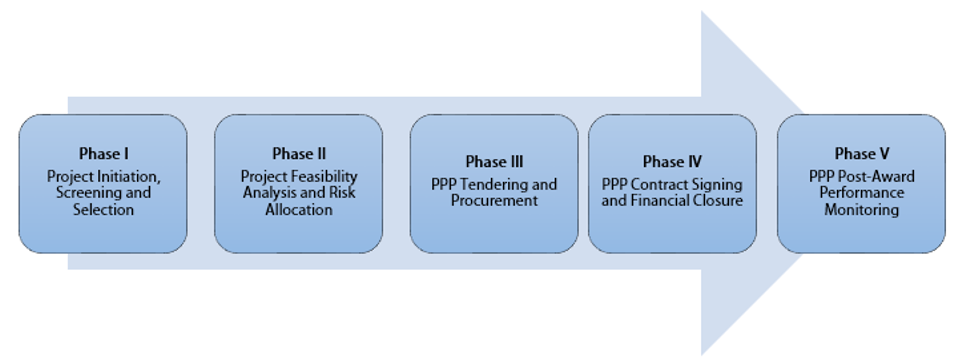

Some CMPs fall under PPP legislation (see Appendix C). In Kenya, while the Wildlife Conservation and Management Act (WCMA) guides the management of NPs, a CMP would be established through the PPP Act of 2013 (see Box 4.1). In some countries, there is confusion over whether the PPP legislation guides CMPs, which can delay the rollout of CMPs. Most PPP legislation outlines a process for selecting, reviewing, and vetting potential PPPs. For example, Malawi’s PPP legislation outlines a four-phase approach (see Figure 4.3). The steps outlined in the Toolkit align with this standard process but should be reviewed to ensure compatibility with the PPP legislation. In some cases, the steps outlined in the Toolkit will provide additional rigor and transparency.

Figure 4.3 - Malawi PPP Process

Source: Malawi PPP Legislation 2011.

In some countries, the PPP legislation does not guide CMP contracts. For example, in Tanzania, the Wildlife Division (WD) and its agent, the Tanzania Wildlife Management Authority, are legally entitled to enter into agreements with other organizations to support the execution of WD’s mandate as provided in the Wildlife Conservation Act of Tanzania, 2009.

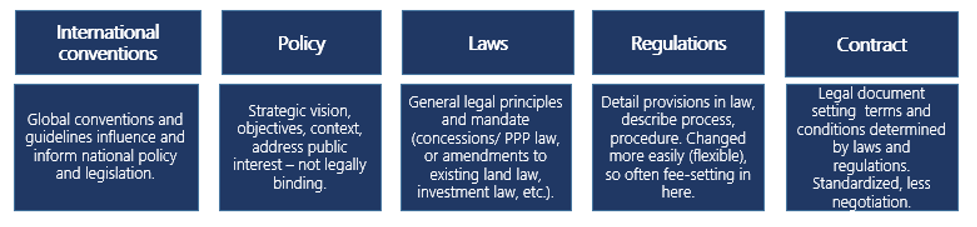

In addition to the overall governing framework for the CMP, the government in the initial state will want to consider the legal framework for other relevant natural resources, beyond wildlife and PA management, to determine which ministries and agencies should be involved in and made aware of the CMP process. The management or exploitation of these assets, such as minerals, carbon, and water could enhance or infringe on a CMP; therefore, it is important to understand these aspects at the onset of a CMP process. The government should also review the country's international obligations to ensure compliance and to support the fulfillment of these obligations through a CMP (see Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4 - Legal Framework for CMPs

Source: Spenceley et al. 2016.

4.3 - Review Agency Goals and Targets

The CA will want to review the wildlife agency’s goals and strategies to determine if a CMP is a suitable tool to address particular challenges. Some countries have embedded the desire for strategic partnerships into the ministry or PA authority strategic and financial plans. In Mozambique, ANAC states in its financial plan the desire for partnerships to help attract financial resources (see Table 4.1). In addition to national policies, the government should review these strategies, plans, and targets to ensure consistency.

Table 4.1 - Embedding CMPs in Laws and Country Level Plans in Mozambique

|

Government Law and Policy |

Section Relating to CMPs |

|

Forestry and Wildlife Law of 1999 (Law 10.99, Article 33) |

Allows management of PAs to be delegated to the private partner |

|

Conservation Policy of 2009 (Chapter III) and Conservation Law of 2014 (Article 4) |

Promotes partnerships "involving local and national authorities, local communities, the private sector and non-governmental organizations" (NGOs) to "enable the economic viability of this policy" |

|

ANAC Creation Decree (Decree 9/2013 of April 10, Article 3) |

Identified as one of ANAC's principle objectives "to establish partnerships for the management and development of Conservation Areas" |

|

ANAC Financial Plan of 2015 |

Recognizes the limited financial resources of ANAC and declares: "The search for more partnerships is an important strategy for ANAC." |

|

ANAC Strategic Plan of 2015-2024 |

"Recognizes the need to involve other actors and partners to ensure resources needed for the effective and sustainable management of CAs" and specifically identifies management models including "public-private-partnerships," "management by the private sector," and "management by NGOs," as well as community management and government management |

Source: Baghai et al 2018.

Once an agency determines that it is open to engaging in a CMP, it will need to consider which PAs are most suitable. Some of the key drivers for engaging in a CMP are described in Chapter 2 and include the restoration of natural capital, enhancing wildlife numbers, and diversifying revenue. The motivation for engaging in a CMP varies and depends on the agency’s vision, goals, and strategy. For example, a PA authority’s strategy for entering into CMPs might be to attract investment and expertise, reduce the financial burden on the agency, or to diversify the tourism product within the country or restore extirpated species. When determining which PAs are suitable for CMPs, the PA authority should frame its review and selection criteria on its agency goals. The ZPWMA, for example, identified the use of CMPs as a strategy for diversifying funding streams for its PA estate (Lindsey et al. 2021). If a PA authority has an annual management budget of $50 million and an annual funding gap of $20 million, and its primary reason for considering a CMP is to reduce its financial burden, the selection of a small park with an annual budget of $500,000 will not substantially help the agency achieve its overall objective.

Most PA authorities have five-to-10-year strategies for the agency and PA network. The selection of PAs for CMPs should support the agency’s strategy. The Uganda Wildlife Authority’s (UWA) 2013-2018 Strategic Plan had very clear targets on financial sustainability (UWA 2013):

Internally generated revenues funding 80 percent of the annual optimal budget.

Internally generated revenues increasing annually by 20 percent.

These clear targets would guide which PAs are most likely to help UWA achieve these goals and where a CMP is the appropriate conservation approach for doing so.

4.4 - Screen and Select Potential Protected Areas for CMPs

The CA should clearly outline the process to be undertaken to identify suitable PAs for CMPs. The selection criteria should be documented and shared with stakeholders to ensure a transparent process and that stakeholders understand how decisions are taken. This will help avoid challenges and delays in the future.

Once the PA authority’s strategy is reviewed (see Section 4.2) and the goals for considering a CMP are agreed, the PA authority should establish the criteria it will use to select suitable PAs for CMPs. The CA should review and consider three key factors: the status of PAs; key drivers for engaging in a CMP; and deterrents and risks for engaging in a CMP (see Figure 4.5).

Figure 4.5 - CMP Variables for Consideration in PA Selection

Source: World Bank. Original figure for this publication.

Status of Protected Areas

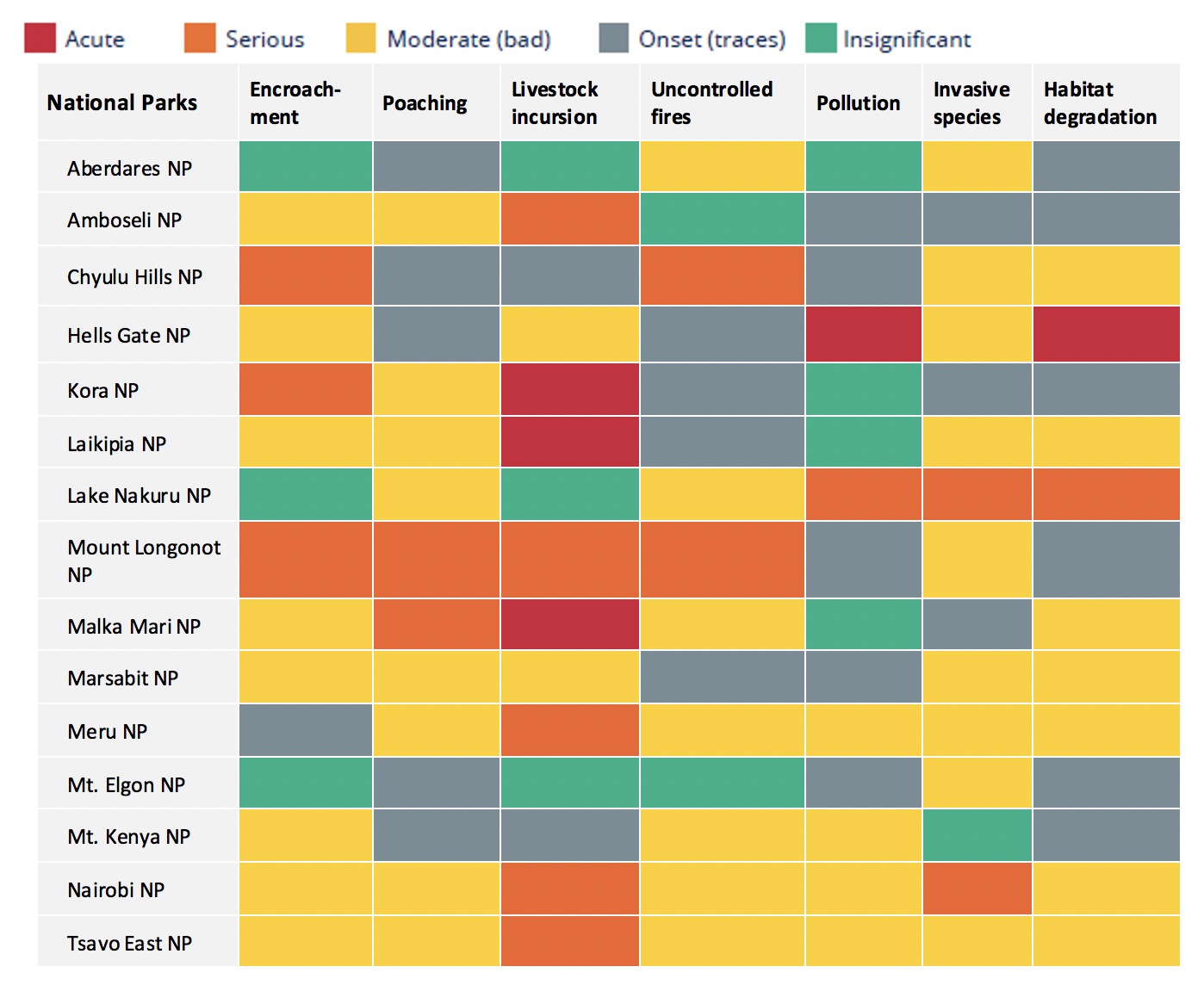

COMIFAC (2019) recommends the establishment of a diagnostic assessment of all PAs to identify sites for CMPs, with the first step being the status of the PAs. To determine the ecological status of PAs, the CA should complete:

Resource inventory of the PA to determine the presence and status of key natural resources (species and ecosystems).

Threat analysis to identify and assess the scope and severity of threats (see Figure 4.6).

Performance audit to assess trends in management effectiveness. There are various tools available to assess management effectiveness, such as the Global Environment Facility Management Effectiveness Tracking Tool (METT) and the Integrated Management Effectiveness Tool (IMET).

Figure 4.6 - Threat Analysis of Selected National Parks, Kenya

Source: Adapted by the African Leadership University from the Kenya Ministry of Wildlife and Tourism, 2021 (Snyman et al. 2021).

These three analyses (resource inventory, threat analysis, and performance audit) will give the CA a good understanding of which PAs need support.

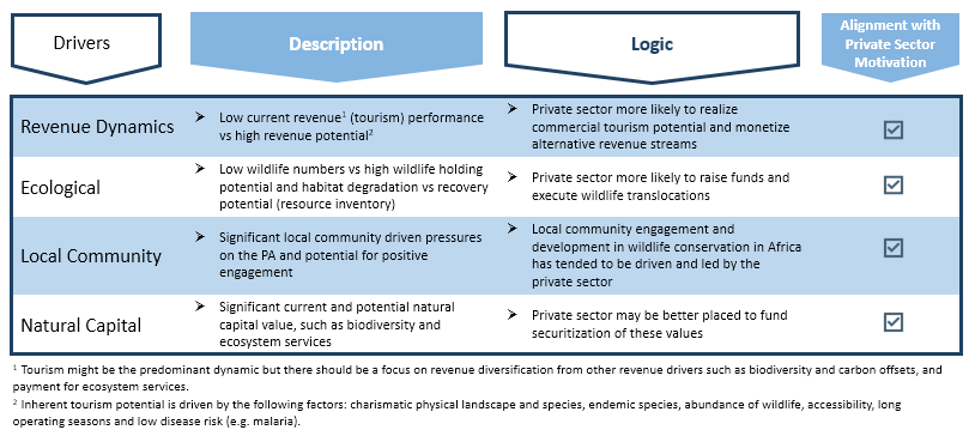

Key Drivers for CMPs

To determine which PAs have potential to perform under CMPs, the CA will want to consider four key dynamics: revenue, wildlife, community, and natural capital (see Figure 4.7). All four drivers may not exist in all cases and can be used as a guide for the CMP selection process.

Figure 4.7 - Four Key Drivers for Consideration in CMP PA Selection

Source: WBG 2020b.

Table 4.2 is a sample tool that the CA may use to consider different dynamics and to vet potential PAs. Certain criteria can be weighted more than others to align with the PA authority’s goals.

Risks and Potential Deterrents

There are a number of risks that the CA should consider as part of the park inventory, assessment, and ranking. While some risks might be effectively managed and mitigated, others may not; therefore, a CMP should not be pursued.

- Security and Safety: Insecurity and instability can hamper the success of a CMP. There are examples of CMPs that have achieved success despite insecurity, such as in Virunga NP in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which is managed between the Virunga Foundation and ICCN through a 25-year CMP. Despite the conservation and economic success (see Box 4.2), VNP has been severely challenged by insecurity. More than 200 rangers have been killed in the line of duty. Similarly, in Garamba NP in the Democratic Republic of Congo, managed between ICCN and African Parks, 23 rangers were killed between 2006 to 2017 (Brugière 2020).

- External Drivers of Threats : The ecological degradation of a PA is one of the reasons PA authorities enter into a CMP. However, if the driver of the threat is outside the PA, a CMP may not be the right tool to mitigate that threat. For example, if the polluting of a central water body in the PA is leading to the decline of key wildlife, and the source of the pollution is outside the PA, over which the partner has no influence, a CMP may not be the right mechanism to address this particular threat. This is why identifying key threats in a threat analysis and ensuring a CMP will help mitigate these threats is key in due diligence and pre-planning.

- Management Trends : It is important to review the management trends within a PA, ideally through a management effectiveness tracking tool. If the scores show an increase in management effectiveness, and effective management is realistically attainable without outside support, a CMP may not be the right tool for shoring up management. Even if the management of a PA is improving, a government may opt for a CMP.

- Flagship Parks : Every country has flagship parks that are recognized by national and global citizens as national treasures, such as Serengeti National Park in Tanzania. These PAs conjure up strong emotions from stakeholders, and careful consideration should be given to the perception of entering into a CMP with a partner. This is not to suggest that flagship parks should not be considered for CMPs; however, if this is one of the first CMPs to be established in a country, a less recognized PA might be the best approach to first demonstrate success (WBG 2020b).

- Land Claims : A CA should carefully consider the risks associated with a CMP for a PA that is subjected to a formal land claim, which may include grievances from local communities that have not been collectively resolved through a grievance mechanism. A legal challenge against ownership might deter partner engagement and donor funding and puts the long-term sustainability at risk. There are cases where the negotiation of a CMP might be part of a claimant’s petition for land rights and can help leverage a positive outcome for the community and conservation (see the Makuleke case study in Appendix D, Figure D.7).

Other risks include: political interference, changing philosophy around the use of CMPs, and human settlement inside PAs. Once the PA authority considers the potential risks and deterrents, the findings can be combined in a table with the drivers for entering into a CMP (see Table 4.2). The CA can weigh certain drivers or detractors to align with its overall strategy.

Box 4.2 - Conflict Risk in Virunga NP, the Democratic Republic of Congo

Virunga NP is managed through a 25-year CMP between the Virunga Foundation (VF) and ICCN. Despite armed conflict and Ebola, all three great ape taxa remain present in Virunga. The population of mountain gorillas has been increasing at a natural rate of growth for five years, which led IUCN to decrease the threat level from critically endangered to endangered. Virunga’s mountain gorilla population is estimated at over 300 compared to only 58 in 1981. Elephant poaching has been steadily declining for 10 years, with herds now venturing into areas of the park where elephants have not been present for several decades. Nine elephant carcasses were found in 2017, six in 2018, and three in 2019. The total area of the park illegally occupied has reduced for three consecutive years while the integrity of all major ecological zones within the park has been maintained. The number of armed groups present in Virunga declined in 2019, allowing rangers to deploy over larger areas and as a result to protect more effectively against poaching, charcoal extraction, and illegal land occupation.

In relation to the improvement to people’s quality of life, VF’s wide-ranging projects have reintegrated thousands of people into legitimate work activities and improved the lives of many more. These projects include major hydropower and related electrification activities, support for farmers and their supply chains, and micro-credit programs. Thousands of young people are working directly and indirectly for VF’s initiatives, reducing the pool of recruits for armed groups (VF Trustees Report 2019).

Table 4.2 - Sample Protected Area Selection Tool: Drivers, and Deterrents and Risks

|

Protected Area Selection Matrix |

Evaluation |

|||

|

Evaluation (Weak (+1), Average (+2), Strong (+3) ) |

||||

|

Category |

Drivers |

Park A |

Park B |

Park C |

|

Revenue dynamics |

Current revenue dynamics |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Presence of commercially successful tourism facilities |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Potential for wildlife-based tourism revenue |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Potential for other revenue generating opportunities |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Community |

Current community relations |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Current community cost |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Current community benefits |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Potential for community benefits |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Ecological and natural capital |

Ecological priority for government |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Natural capital value |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Evaluation (Low (-1), Medium (-2), High (-3) ) |

||||

|

Category |

Risks and Detractors |

Park A |

Park B |

Park C |

|

Detractors and risks |

Security and safety |

- |

- |

- |

|

External drivers of threats |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Management trends |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Flagship parks |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Land claims |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

TOTAL Score |

|

# |

# |

# |

Source: Adapted from WBG 2020b.

4.5 - Screen and Select the CMP Model for the PA

Once the CA has selected which PAs might be suitable for CMP consideration, it will then want to consider the most suitable model for the respective PA. PAs are diverse and face a range of unique threats; therefore, the model selected should take all of these aspects into consideration. Some countries utilize one CMP model, such as the Republic of Congo, while other countries utilize different models, such as Mozambique (see Table 4.3). Having one kind of CMP model might make contract oversight and management by the PA authority easier, and decrease time to develop and execute an agreement, but certain PAs require different models. Also, being open to a range of models increases the breadth of potential partners.

Table 4.3 - Types of CMP Models Used in African Countries

|

Country |

Partner |

Protected Area |

Type of CMP |

|

Republic of Congo |

All Delegated CMPs |

||

|

African Parks |

Odzala-Kokoua NP |

Delegated |

|

|

Noé |

Conkouati Douli NP |

Delegated |

|

|

WCS |

Nouabale-Ndoki NP |

Delegated |

|

|

Democratic Republic of Congo |

Delegated and Integrated CMPs |

||

|

African Parks |

Garamba NP |

Delegated |

|

|

AWF |

Bili-Uele PA |

Bilateral |

|

|

Forgotten Parks Foundation |

Upemba NP |

Delegated |

|

|

Virunga Foundation |

Virunga NP |

Bilateral |

|

|

WCS |

Okapi WR |

Delegated |

|

|

WWF |

Salonga NP |

Bilateral |

|

|

WWF |

Dzanga-Sangha NP |

Bilateral |

|

|

Malawi |

All Delegated CMPs |

||

|

African Parks |

Liwonde NP |

Delegated |

|

|

African Parks |

Majete Wildlife Reserve |

Delegated |

|

|

African Parks |

Mangochi Forest Reserve |

Delegated |

|

|

African Parks |

Nkhotakota Wildlife Reserve |

Delegated |

|

|

Mozambique |

Bilateral, Integrated, and Delegated CMPs |

||

|

African Parks |

Bazaruto Archipelago NP |

Delegated |

|

|

Carr Foundation |

Gorongosa NP |

Integrated |

|

|

IGF Foundation |

Gile National Reserve |

Bilateral |

|

|

Peace Parks Foundation |

Zinave NP |

Bilateral |

|

|

WCS |

Niassa National Reserve |

Bilateral |

|

|

Zimbabwe |

Integrated and Delegated CMPs |

||

|

African Parks |

Matusadona NP |

Delegated |

|

|

FZS |

Gonarezhou NP |

Integrated |

|

Source: Compiled with information from: Baghai et al. 2018; Baghai et al. 2018b; Baghai 2016; Brugière 2020; NGO and PA authority websites; and communication with CMP NGO and PA authority partners.

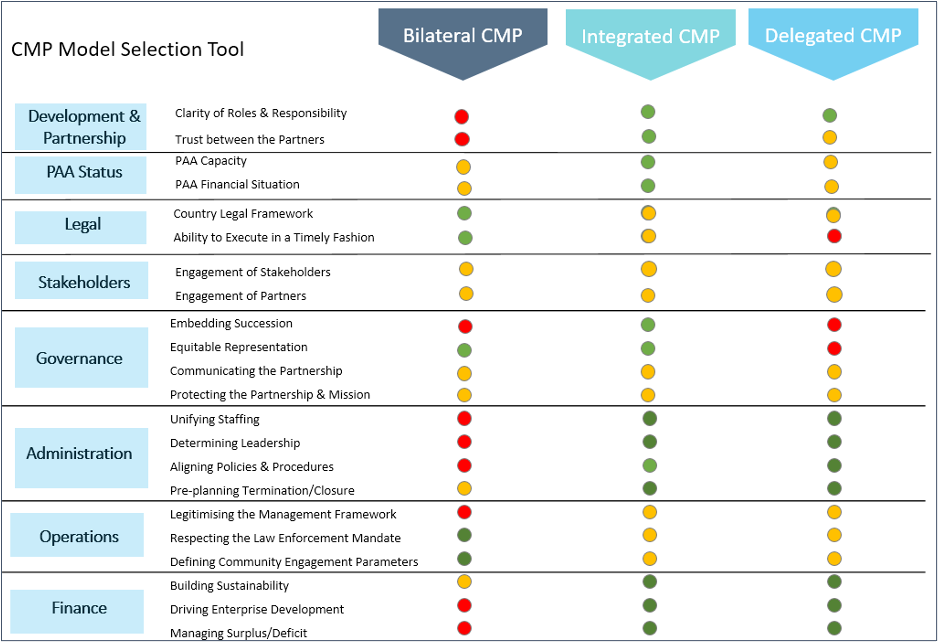

The CA should review the CMP best practice principles in Section 3.5 and review and rank the relevant principles to determine the most appropriate CMP model. A sample selection tool is provided in Figure 4.8 where the color aligns with the ability of the model to meet each criterion. Some of the best practices pillars and principles were consolidated in this example.

Figure 4.8 - CMP Model Selection Tool to Determine Suitable PA Model

The color coding is hypothetical and should be completed for each PA.

Source: Adapted from WBG 2020b.

Note: The color aligns with the ability to meet each criterion: green indicates yes; orange likely; and red no. In this illustrative example, the integrated CMP model is most suitable.

It is important that the CA review suitable CMP models prior to the tendering process so that it understands the pros and cons of each model. However, the CA will not want to limit bids to that particular model and instead should keep options open during the concession process.

4.6 - Review National and Regional Plans

CAs should also consider how PAs might fit into national development plans or strategies. Many countries have identified tourism (namely NBT) as a key pillar for economic development; in these cases, the effectiveness of PAs is directly linked to development objectives. For example, Kenya’s Vision 2030 names tourism as one of six priority sectors that will be tapped to boost economic growth, and the tourism pillar leans on developing and improving tourism in national parks, reserves, lakes, forests, and other PAs. Kenya also recognizes the importance of wildlife conservation and management in supporting its social development pillar (see Table 4.4). NBT, research and ecological monitoring, and the development of wildlife linkages are all contingent on effective PA management.

Table 4.4 - Pillars of Kenya’s Vision 2030 Plan that Rely on PAs (Established Pre-COVID)

|

Selected Pillars |

Examples of Initiatives that Use PAs |

|

Economic Pillar: Tourism Sector |

Under-utilized Parks Initiative Infrastructural improvements and development initiated during the First Medium Term Plan will be continued. Products in Meru, Mt. Kenya, Tsavo East, Tsavo West, Mt. Elgon, and Ruma NPs shall be repackaged to increase the diversity. Specific actions will include: ● Marketing the under-utilized parks ● Providing incentives such as concessionary land leases and tax incentives ● Revamping the KWS ranger force to curb poaching and insecurity (including HWC through installing electric fencing around the parks) Premium Parks Initiative Infrastructural improvements in Amboseli and Lake Nakuru NPs will be undertaken. Segmentation based on product and price in the parks will be sustained. Facilities to be rehabilitated include Lake Nakuru NP observation, picnic/campsites; campsites and visitor facilities across the parks; and upgrading road network of about 300 kilometers.

Niche Products Initiative 2 Eco-tourism. Sites for these products will be developed in the western region of Kenya and include Kakamega Forest, Ruma NPs, and Mt Elgon and Mt Kenya Regions. |

|

Social Pillar: Environment, Water, and Sanitation |

Wildlife Conservation and Management — This will involve identification, mapping, and documenting hotspots and boosting their connectivity to enhance ecological integrity of habitats for wildlife. In addition, wildlife research stations will be refurbished and equipped; ecological monitoring programs will be enhanced in all PAs and a national wildlife research, information, and database will be developed at KWS headquarters. Wildlife security and management will be enhanced. To promote eco-tourism among communities living with wildlife, a program of mapping and securing community areas with eco-tourism potential shall be initiated. Secure wildlife corridors and management routes — Most wildlife corridors and migratory routes have been interfered with by human activities. Strategies will be developed to reclaim them so that wildlife continues providing the base for the tourism sector. Actions include preparing physical development plans to map and secure the wildlife corridors and migratory routes to minimize human-wildlife conflict. |

Source: Kenya’s Vision 2030.

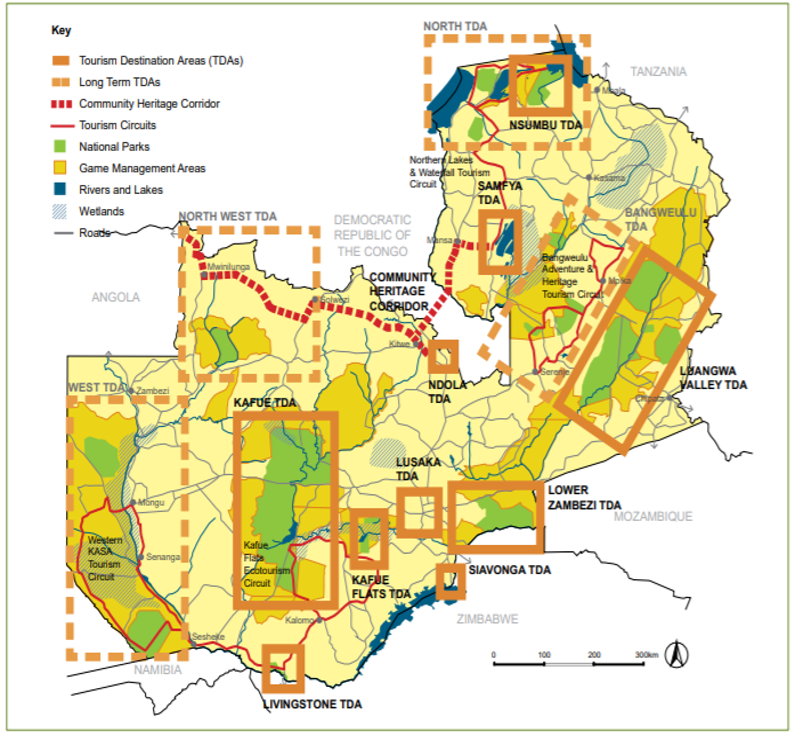

Tourism-specific plans tend to rely heavily on PAs. For example, Zambia’s Tourism Master Plan (2018-2038) is the country’s first national strategic framework to guide the development of the tourism sector, which is prioritized for economic diversification under Zambia’s Vision 2030 and Seventh National Development Plan (2017-2021). Much of the plan is anchored in increased investments and enhancements in tourism in PAs, as well as strengthening tourism management (see Map 4.1). The Seventh National Development Plan also cites restocking NPs as one of five key strategies for tourism development. These priorities can help guide PA authorities on deciding whether CMPs are right for which PAs.

Map 4.1 - Priority Tourism Development Areas under Tourism Master Plan (2018-2038), Zambia

Source: Zambia Tourism Master Plan 2020.

Note: Zambia’s tourism Master Plan is centered on PAs.

In addition to national, sub-national, and regional integrated development plans, CMPs should be considered in the context of large landscape planning. Biodiversity protection requires large, intact landscapes and seascapes that comprise a mosaic of land use and ownership schemes. These large areas support natural processes and enable the movement of species. PAs alone are not enough to sustain healthy wildlife populations in the face of a changing climate and increasing human development ; therefore, CAs and conservation partners commonly plan at a landscape scale. In Kenya, Amboseli NP is a small, yet important PA that relies on the surrounding community and privately owned lands for wildlife movement and habitat. KWS, rather than planning at park level, developed the Amboseli Ecosystem Plan, which takes into consideration the larger ecosystem dynamics (Amboseli Ecosystem Trust 2020). When planning for a CMP, the partners should consider how the PA fits into the larger mosaic and if the CMP is compatible with and can advance relevant government strategies and land use/development plans. In addition to national, sub-national, and regional integrated development plans, CMPs should be considered in the context of large landscape planning. Biodiversity protection requires large, intact landscapes and seascapes that comprise a mosaic of land use and ownership schemes. These large areas support natural processes and enable the movement of species. PAs alone are not enough to sustain healthy wildlife populations in the face of a changing climate and increasing human development ; therefore, CAs and conservation partners commonly plan at a landscape scale. In Kenya, Amboseli NP is a small, yet important PA that relies on the surrounding community and privately owned lands for wildlife movement and habitat. KWS, rather than planning at park level, developed the Amboseli Ecosystem Plan, which takes into consideration the larger ecosystem dynamics (Amboseli Ecosystem Trust 2020). When planning for a CMP, the partners should consider how the PA fits into the larger mosaic and if the CMP is compatible with and can advance relevant government strategies and land use/development plans.